In May of 2020, nearly a third of workers at a Tyson Foods plant in Waterloo, Iowa contracted COVID-19. Like many workers at the time, they sought out their local union for support, UFCW Local 431. However, they “…kept waiting and waiting, and nothing,” Joe Gorton, former union president at University of Northern Iowa, told The Courier about UFCW Local 431

It’s a story that’s all too familiar for Enrique Villeda.

The union reps that were meant to help him hurt him in the end.

Stockyard worker Villeda says that UFCW Local 2 President Martin Rosas failed to act in good faith when filing a grievance to re-secure Villeda’s position as a Seaboard Foods stockyard worker in Guymon, Oklahoma.

Villeda worked for Seaboard Foods for more than a decade, but in April of 2020, his job was on the line after he argued with management about a change in work hours that had already been settled, says Villeda.

(A year earlier, Seaboard Foods in Guymon had also changed its slaughtering rules after the USDA lifted certain slaughter speed limits. Instead of 1,100 slaughters per hour, it would be 1,230 to 1,300 an hour. The change resulted in an uptick in worker injuries.)

According to Villeda, they believed his choice of words, “If it’s a war you want, it’s a war you’ll get,” amounted to a threat; Villeda adamantly denies this and says they took his words out of context.

After the argument, Villeda turned to President Rosas and asked him to file a grievance complaint under the union contract when Seaboards put his job on hold.

“I talked to Martin, the president of the union, and I told him what happened,” Villeda recalled, speaking in Spanish. “And he told me, ‘No, how are they going to do that? That’s not a threat. Don’t worry. Go to your house, don’t worry. The union is going to fix this. Apply for unemployment. Now that there’s this pandemic, you’re going to get more money being in your house. Have fun during your vacation; the union’s going to fix this.'”

But Rosas didn’t fix much.

More than a year later, Villeda is without his job at Seaboard Foods and is still looking for answers about how a union president like Rosas can go without any punishment from the NLRB or the union itself.

BEFORE Villeda met Rosas, he had worked in a union in Guatemala. In 1987, he had started working as a leader for the SITRABI union (Sindicato de Trabajadores Bananeros de Izabal).

He says he would have stayed in Guatemala for many years, but in September 1999, SITRABI and the banana plantation company Bandegua (a subsidiary of Del Monte Fresh Produce) attempted to form a new collective bargaining agreement together.

At that point, Bandegua let go of 918 workers, and a month later, knowing SITRABI was planning to protest their terminations, they commissioned nearly 200 armed men to storm the SITRABI headquarters in Moralez, Izabel.

They then forced men at gunpoint, which included Villeda, to renounce their leadership over radio broadcasts and falsely claim they had reached an agreement.

That experience set off a series of events where Guatemala and the U.S. government ultimately moved Villeda to Los Angeles along with another five families because they all feared for their safety.

After moving to Los Angeles, Villeda moved two more times, and eventually, he met Rosas, who at the time was a secretary-treasurer of UFCW Local 2 in Liberal, Kansas.

Villeda became a member of the UFCW and recalled that Rosas was congenial with him. He even told Villeda that his background working in unions in Guatemala would be helpful for the union, says Villeda.

But before he could have Villeda work for him in the union as a union organizer, Rosas told Villeda he needed to first work at a meatpacking plant. Then after that trial period, they would talk.

“Nine months passed and those basically were all empty promises,” Villeda said.

While they continued keeping in touch periodically, Rosas never materialized on any of his promises to give Villeda work.

Fast forward to April of 2020. Villeda’s job is in jeopardy at Seaboard Foods. Rosas, once secretary-treasurer, is now the President of UFCW Local 2. So, Villeda called him and pleaded with him to take action about his concerns about his job.

Villeda says Rosas told him to apply for unemployment benefits and over the course of 10 days call the company’s telephone number for absent work to see if they had let him go. He said he called for 21 days, and by then, they still had not let him go.

However, according to Villeda, after the initial suspension, Seaboards had decided they would reassign Villeda to a butchering position because they believed he was a violent threat.

“It was ridiculous because before my work tools were a plastic board and a plastic palette to move the animals and where they were sending me, they were giving me two knives.”

According to Villeda, Rosas also told him not to worry. Even though they transitioned him into working another position, he was sure that eventually they would fire Villeda, which would mean that the union was going to pay for all of Villeda’s missing work. If necessary, they’d take Villeda to arbitration to get his job back.

“The thing is that day…Martin told me that day to be careful of accepting any job change because, [he told me,] ‘I know how these companies work. They are going to want you to work a job that’s harder, more tiring, more than where you were before so that you will get overwhelmed and leave. Don’t worry, the union is going to fix it, and if it’s necessary, we are going to take the case up to arbitration.'”

Two months had passed, and Rosas and UFCW Local 2 Director of Organizing and Membership, Mayra Carbajal, had closed the third step of the grievance process. It was June now, and Villeda says Rosas told him he should appeal the decision before the UFCW Local 2 board as a way to speed up the resolution.

Then, on September 29, 2020, the local board denied Villeda’s appeal to submit his case to arbitration.

It was a letdown, but Rosas told Villeda, once more, not to worry.

FOR his work as the local UFCW president, Rosas makes $304,815 a year (total compensation), a fact that Villeda finds astounding – it’s more than the salary of the vice president of the United States, he says.

Jarrett Brown, a factory worker and labor activist in Green Bay, Wisconsin, also finds this stat astounding, if not frustrating.

In 2010 he started a Facebook group while living in Kansas called UFCW Local 2 Reforma, a group that shares information about union members’ rights while also warning Spanish-speaking union members at UFCW about ways companies and union reps could take advantage of them.

“The reason that I started writing online is because there needs to be some accountability in the union,” says Brown. “The union members need to have a voice in what happens. And if the union members say, ‘No, it’s okay for us to pay [Rosas] $330,000’ – if that’s what the union members want, then that’s okay. But the problem is that the union members are being completely left out of the process and decisions are being made mostly by marching in the dark.”

Brown started the group after seeing how workers, who didn’t have a great command of the English language or union rules and regulations, were getting duped by union officials, the exact people who were supposed to be helping them. Brown’s work mainly involves helping those in Kansas and Missouri, like in the case with Villeda.

“The people who work at the plants have certain rights by law or by regulation or by policy,” says Brown. “But those rights aren’t enforced, which means those rights don’t exist in reality.”

Not surprisingly, Villeda’s experience is something Brown had seen before. The way that Rosas dangled a job as a union organizer in front of him from the very beginning, as Villeda claims, or, the way that he kept leading him on, or, the way he did the minimum possible to show he was “investigating” the case – all that is common practice Brown says.

“What it comes down to is the NLRB gives workers six months to file a complaint and so what the union does is they tell the workers, hey, you know, just wait, we’re talking to the company, we have a meeting, and they keep kicking the can, and then the six months passes and they have no recourse,” says Brown.

While there have been success stories of workers getting some justice with the help of Local 2 Reforma (one woman successfully lobbied for her job thanks to becoming aware of the six-month rule), Brown notes that he still sees the same issues crop up of UFCW union reps not doing much work to protect workers.

“Whether it’s under a Democratic president or a Republican president, over time it hasn’t really been reformed in order to do what’s in the best interest of the workers,” he says.

MIKE DUFF, Winston S. Howard, Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Wyoming College of Law, says situations like Villeda’s are unfortunately not uncommon, especially in the domain of NLRB (National Labor Relations Board) law and how unions are regulated.

As for what Villeda can do?

“I would say not a heck of a lot,” he says. “American labor law is just weak. It’s weak with respect to protecting employees whose rights are being violated by the employer. It’s weak with respect to rights that employees have with respect to the union. It’s just weak.”

The cases that the NLRB are interested in are those that are arguably more cut-and-dry and more serious from a legal standpoint, Duff says, such as sexual harassment or racist remarks, for instance. But in cases where the rep has been negligent, that’s another story.

“If the union is slow, if they’re sloppy, if they’re vaguely delaying, if they’re not sufficiently aggressive or, you know, pursuing matters on behalf of the bargaining unit the law is almost impossible to activate in situations like that,” he says. “The idea is that, look, if your union is that full of crap, right? Yeah, eventually, you can recertify the union and replace them with another one.”

But, replacing union leadership is no easy feat. Under AFL-CIO rules, member unions like the UFCW have exclusive jurisdiction over specific industries, creating very little competition for potential members.

Plus, union elections of massive locals such as Local 2 that represents thousands of workers spread over various workplaces, can be very difficult for rank-and-file challengers to win. The result is that there is very little accountability for union leaders who don’t serve their members like UFCW Local 2, President Martin Rosas.

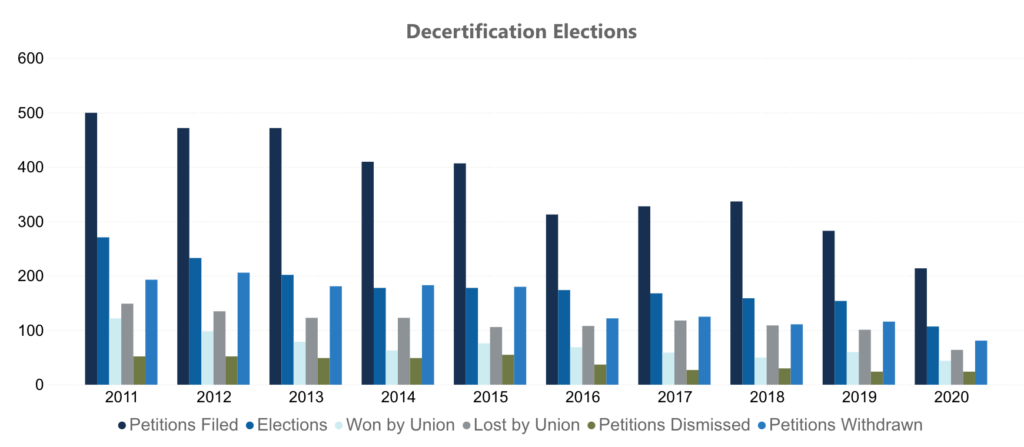

Over the past decade, attempts at decertifying unions have been dropping, with 500 petitions filed in 2011 to 214 in 2020. According to the most recent data from the NLRB, elections have also dropped 60 percent from 271 in 2011 to 107 in 2020.

“The thrust of the law is that ‘mere negligence’ in a union’s handling of a grievance is almost never enough to make an NLRA violation,” says Duff, noting that under the Trump administration, Trump’s General Counsel, Peter Robb, attempted to refine and update the “duty of fair representation” rule, which, after he was replaced, returned to the “status quo.”

“It’s very tough to prove and I doubt a Biden NLRB will be interested in issuing complaints against unions,” he says.

The 2020 and 2021 NLRB numbers also show that complaints against unions are historically low. But for the past three years, UFCW has consistently ranked as the union with the fourth most complaints against it, with SEIU, IBT, and UAW rotating in the top three spots.

More than a few times, we attempted to contact Martin Rosas for this story. Rosas returned one call and left a message. But subsequent interview requests through email and phone all went unanswered.

After initially making plans to speak, this pattern of missing calls and then seemingly disappearing also happened to reporters at The Courier. According to The Courier:

“Dozens of phone calls and voicemails over two months to UFCW Local 431 representatives from The Courier went unanswered. Bob Waters, union president, answered the phone Dec. 22 and said he was ‘in the middle of something’ but would be available later that day. He never answered subsequent calls.”

Likewise, Brown says this kind of half-communication style has been happening with union reps. For instance, they’ll call in and “check in” with the worker to make sure they’ve done just enough work to appear involved or show that they’ve “investigated” the employee’s grievance.

“That’s evidence that they’re actually doing their job,” Brown says. “So it’s going to make it hard for [workers] to win the case.”

Seaboard Foods Senior Director of Communications and Brand Marketing, David Eaheart, also declined to comment on any of Villeda’s claims, noting, “Because this request is about an individual’s personnel issue, we are unable to provide comments or information.”

AFTER the local union board denied Villeda his arbitration appeal on September 29, Villeda says Rosas said he would get him a labor lawyer, a legal opinion in front of the board, and that he would go to the company himself to find a solution. Villeda says it was “a bunch of lies.”

None of that happened, and when it didn’t, Rosas turned to the NLRB to issue his complaint about how Rosas handled his case, namely: “by refusing to process the grievance, regarding his transfer, suspension and discharge for arbitrary or discriminatory reasons or in bad faith.”

But, by then, it was October. Six months had passed and Villeda was no longer within the NLRB’s six-month statute of limitations. And, because the majority of Villeda’s communication with Rosas was over the phone, he had very little in terms of tangible evidence.

Villeda ran out of options.

“He should have been honest with me from the beginning,” Villeda says. “It would have been better if he told me, ‘Enrique, we’re not going to win your case, it’s better that you change your job, we’re not going to be able to do anything.’ Instead, he kept feeding me lie after lie for six months, and in the end, I was left with nothing.”

Villeda now works at another pig farm where he makes less pay with fewer benefits, although he jokingly adds about the farm’s non-union status, “I am no longer sure whether it will be better to have a union there or not.”

Donate to Help Us Cover the Fight for Immigrant Workers’ Rights