Five years ago today, in 2015, when I was illegally fired from Politico, there were more Black men on my legal defense team (three) than working in Politico‘s entire 250-person newsroom.

As an autistic child, who attended the last school in Pennsylvania that was still under federal integration, Woodland Hills, this didn’t surprise me: Black role models and teachers had always played a vital role in overcoming the adversity and bullying that many disabled children like me faced.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that a newsroom that was 93% white without a single Black editor would be a place where management would break disability law. Newsrooms that don’t promote racial diversity certainly don’t encourage neurodiversity when it comes to autism.

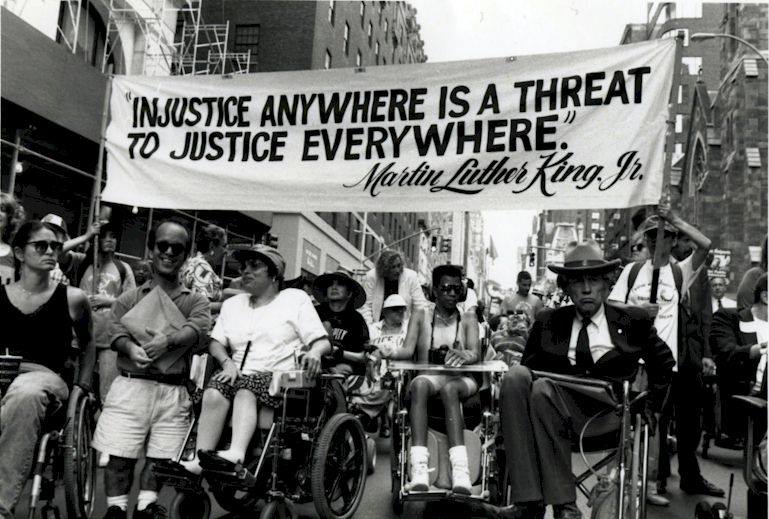

Throughout history, Black activists have always played a role in inspiring the disabled of all races to fight for their rights. Indeed, veteran Black civil rights activists trained the first disabled folks who engaged in civil disobedience to demand accommodations in the 1970s.

In 1977, The Black Panther Party was the biggest backer of the “504 Sit-In,” which was the longest non-violent occupation of a US federal building in US history. It forced the Carter Administration to issue the first federal regulations on disability rights.

Sadly, until the recent Netflix hit documentary “Crip Camp,” this history of Black civil rights leaders leading the fight for the disabled of all races had largely been forgotten.

“I never even knew it. It was actually a white friend, who took a disability course, told me about it,” says Black autistic activist Morénike Giwa Onaiwu, the Innovation Director of the Autistic Women and Non-Binary Network and co-editor of “All the Weight of Our Dreams: On Living Racialized Autism,” an anthology of art and writing entirely by autistic people of color co-edited with Lydia Brown and E. Ashkenazy.

“When I learned that, it made perfect sense. I knew a lot of the language from the civil rights movement, and a lot of the tactics were similar, but not that the civil rights movement was really the spirit and the role model behind the disability rights movement,” says Giwa-Onaiwu.

She says part of the problem is that whites taking the lead of the disability rights movement have largely erased this history from the mainstream narrative.

“It was ‘Ok, thanks for this model, your template, we are good and you can go now,'” says Giwa-Onaiwu.

Indeed, the federal integration consent decree that established my high school, Woodland Hills, was formed in 1982 during this period, where Black activists insisted on disability measures that later benefited me as an autistic.

During my childhood, the presence of Black guidance counselors, journalism teachers, and social studies teachers played such a crucial role in helping me to persevere. But in journalism, I never had a single Black editor.

Well, technically, I never had a Black editor. Thank God, I did find one Black role model fighter; my union rep Bruce Jett, the battle-hardened NewsGuild union representative, who was fired while leading the New York Daily News strike in 1991 where African-American reporters and staffers were fired at twice the rate of white staffers to bust the union.

Next to my friend and mentor, William Greider, I can’t think of anyone who had a bigger impact on my ability to write about the labor movement than Bruce Jett.

Unfortunately, most reporters don’t have any Black role models in the newsroom. This hurts not only Black reporters and our ability to cover racial justice. Still, it also hurts our ability to create inclusive environments for people of color, women, minorities, and disabled people like me.

Nationwide, just 6% of all editors in journalism are Black, according to a 2019 survey conducted by the American Society of News Editors. (Sadly, no organization surveys for the percentage of disabled reporters employed in newsrooms).

“Over my 15 years in the business, I have had two Black editors,” veteran Black reporter J. Brian Charles recently told me.

“Our job is to chronicle the human condition, and the human condition is broad,” said Charles. “Editors, though, tend though to hire people that think like them.”

Doc Allen

The newsroom where I got my start in journalism, WHHS-TV, the high school station of Woodland Hills High School, or affectionately known in Pittsburgh as “Woody High,” is very different and to this day is still the only newsroom I worked in that was run by a Black woman: Doc Allen.

“I played football all through high school, then got hurt that summer,” says Justin Udo, a Black veteran of CBS radio stations and my co-host at WHHS-TV, whom I first met when we were young kids playing PeeWee football together.

“Doc Allen had one of the biggest impacts in my life ever,” says Udo, now a reporter at KYW. Udo has been in the thick of it getting tear-gassed while covering Black Lives Matter in Philly.

“I remember Doc Allen saying, ‘You did a great job calling basketball last year,’ and she said, ‘I want you and Mike Elk to do it,’ and I remember she loved your voice, she loved your voice, she heard you walking down the hallway,” says Udo.

“If anyone’s voice was ever created as a godsend for radio with no training, it was you Mike–you’re (a) booming voice with no yinzer accent behind it,” says Udo, who for years has recruited me to do a labor reporting session.

For those unfamiliar with the term “yinzer,” it refers to the strange Northern Appalachian accent of Pittsburgh native defined by our usage of “yinz” instead of “y’all” or “youse.” Like “Yinz wanna red up a little n’ go dahntahn n’ git some kilbassas n’at?”

While I was socially awkward and avoided eye contact as an autistic, puberty had left me with a very deep voice. And years of speech therapy as an autistic, who struggled with enunciation, taught me how to hide my yinzer accent.

One day, Doc Allen, whose studio I frequently passed on my way to class, stopped me and said, “Oh, I just love your voice. I just love it. You have a broadcast voice–you could have a real career in journalism.”

While I loved writing and hoped to use my writing skills somehow, Doc Allen’s suggestion was the first time I considered going into journalism. Working for Doc at WHHS-TV was exciting.

Woody High’s football program rated in the top ten in the nation–USA today even profiled our stadium, which could fit 12,000, and our signature Woody High haluski, a traditional yinzer Polish cabbage dish.

Thousands of people throughout the lower Mon Valley and Pittsburgh watched those broadcasts as future Chicago Bear Safety Ryan Mundy led us to our second state championship game.

At WHHS-TV, I found that my ability as an autistic to intensely focus, block everything out, and quickly analyze things served me well in the rapid, fast-moving world of journalism.

After football season, I started volunteering and writing for the Independent Media Center (remember those?) covering protests in the lead up to the Iraq War in 2003; getting my big viral hit when Portside picked up my account of getting arrested as a 16-year-old with 121 others and witnessing cops beating up protestors in the Allegheny County Jail.

It was Doc Allen, who opened new doors into journalism for me and many others who traditionally wouldn’t be considered journalists. I still share a love of making TV and was thrilled recently when Black CNN host W. Kamau Bell asked me to work on a recent “United Shades of America” special on systemic racism filmed in part in Braddock just a little over two miles from my parents’ house.

“I didn’t see a lot of people, who looked like me on TV in Pittsburgh,” says Udo. “I remember that was one of my original reasons forever wanting to be a reporter was because of the inspiration that she had given me.”

“She introduced me to Dick Tracy and Gunsmoke, and all of these old radio shows to really make that ‘theater of the mind and understand how your voice can really stand up and tell a story,” says Udo. “And it’s the reason why I love doing what I do to be able to paint that picture when I am on 52nd and Arch in West Philly with tear gas being shot at me by police just feet away from my head, to be able to paint that picture for people and to be able to stand up and give a voice to the people that don’t have a voice.”

The Importance of Black Role Models for Disabled Youth

As a child attending Woodland Hills, I had plenty of Black role models. They shaped me into the labor reporter that I am today and my ability to understand the complexity of diverse, multiracial social movements.

When I was being bullied or teased as kid, these types of Black role models helped me to understand that being autistic wasn’t just okay, but added valuable diversity, or “neurodiversity,” as Steve Silberman, author of the New York Times Best Selling book: Neurotribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity, refers to it.

“One way to think of neurodiversity is to think of it as human operating systems… just because a computer isn’t running windows doesn’t mean that it’s broken,” writes Silberman.

However, young autistics don’t often have role models to emulate to realize the value of neurodiversity.

“It’s easy to forget that autistic adults did not emerge into the public eye until Oliver Sacks wrote about Temple Grandin in the early 1990s,” says Silberman of the period when I was growing up as a child in Pittsburgh. “So before that, the concept of an autistic adult was completely unimaginable except for the fictional character that Dustin Hoffman played in ‘Rain Man.'”

He adds that as a gay youth growing up in the 70s, he benefited immensely from seeing the first openly gay adult on TV, but says that most autistic adults of my generation didn’t have similar role models on TV.

“Kids with neurodivergent conditions like autism and ADHD did not really have visible role models, and visible role models are so important because they teach you how to have a successful life even if the deck is stacked against you,” says Silberman.

“We, as Black people, make concessions already for people to be different,” says autistic Black disability rights activist Morénike Giwa-Onaiwu. “You can be loud or not, you can be expressive or not,” describing how many autistic people are considered too intense for most white people.

“Whereas white parents might get hysterical about their kids being autistic, Black community or Latinx community or other communities are like ‘Oh, that’s just who they are, who cares if JoJo likes to put everything in lines, Mary gets a little overwhelmed so just be careful with the noise.’ Black people already make those concessions for diversity,” says Giwa-Onaiwu

“That’s why white autism moms feel so isolated because if you can’t do this, this way then, ‘oh something is wrong’ with you – that’s white culture, and it’s scary,” she says.

The need to have a mentor of color is vital not just for students of color, but like so many marginalized groups overall. As my high school classmate Summer Lee, the first Black woman elected to the State House from Western Pa, remarked this past winter at a teachers union forum on public education:

“Everybody talks about how important it is for students of color to have teachers of color. Ok. But it would be nice if they also mentioned how it’s also important for white kids to have teachers of color and a culturally representative education!”

The Federal Consent Decree That Changed My Life as a Disabled Student

As a kid, I had an excellent education because Black folks had fought for my rights as a disabled student as part of the federal civil consent decree established in 1982. The order was in place until my senior year of high school. I received individual support, accommodations, an individualized education plan, and support from guidance counselors as I faced merciless taunting.

Invariably, the taunts would often lead to fights; invariably leading me to the office of a Black guidance counselor, Mr. Jones.

After my older brother died right as I began junior high, and the taunting by other kids become overwhelming, I found myself meeting regularly with Mr. Jones.

On some days, Mr. Jones would really challenge my white privilege as he brought in Black kids who often spoke of their frustration with white teachers. Of course, I was struggling with the loss of my brother. But Mr. Jones would often talk with kids struggling with poverty and widespread racism.

“You don’t realize the opportunities that you have in your life that these kids would kill to have,” Mr. Jones would tell me.

Many of the Black kids that I met in this group session would share their anger at the racism. And I would share my rage at the racism directed at these Black kids.

They also opened my eyes to the racism they faced from white teachers and the excessive punishment that far exceeded whatever I faced as the son of a respected Jewish labor leader.

It was an early lesson in finding allies when you’re marginalized and one that would shape my organizing experience for the rest of my life.

“You found allies because you were going through similar things in terms of being marginalized and discriminated against, being called names and not having your needs met for different reasons, but it was clear to you that there was this tension,” says Morénike Giwa Onaiwu.

Being disabled, I often felt like I was subhuman – that people told me I couldn’t do the things other folks could. My own grandmother, an Italian immigrant, told me as a teenager that she didn’t think I was a “breeder” and for many years, I believed this.

But in those sessions, Mr. Jones really made me feel like my anger and frustrations were natural and that I had the opportunity to struggle.

“Channel that anger. You got the opportunity to do big things with your life,” he would tell me.

The federal consent decree placed on Woodland Hills was far and expansive; it dictated that as a child, I enjoyed a rich display of African-American literature, reading folks like Ralph Ellison, Zora Neale Hurston, James Baldwin, and Countee Cullen while attending high school.

I took an African-American History class, where I was the only white guy taught by a young Black teacher Mr. Hickman. My face still lights up with joy whenever he likes my work on Twitter. In his class, I learned how to perfect the most valuable journalism skill: to shut the fuck up and listen, really listen.

His teaching concept of “double consciousness” spoke to me as an autistic because I knew there was the way that I saw myself and the way that others saw me: “crazy.” In those classes, I found a way to overcome how the rest of society saw me and gave me confidence in my ability to be different.

The world of corporate media wouldn’t be that way at all.

“Being young and naive, I thought that Woodland Hills was a microcosm of how the world was: it’s diverse. I remember having friends black, white, different colors, people from different socio-economic backgrounds, and all of us being able to work together, for the most part, and getting along,” says Udo. “It was a great experience and one that has helped me as a reporter as I look at different perspectives and situations that I may be thrust into.”

“Woodland Hills created a false utopia for me, it was good, it was needed, it helped me as an adult, but it was not what life is,” says Udo.

In the white world of corporate media, I very quickly learned that the kind of Black folks, who as an autistic had been my allies, weren’t there.

The Erased History of Black Civil Rights Activists Training the Leaders of Disability Rights Movement in the 1970s

The excellent 2020 Netflix “Crip Camp” documentary shows (Michelle and Barack Obama were executive producers) Judith Heumann and other activists brought up young Black activists from the South in the late 1960s so they could learn from them; renewing interest in the overlooked history of how Black civil rights leaders, veterans of the 60s, inspired and trained the multiracial disability activists.

In 1977, disabled folks, taking a page out of the Civil Right movement, occupied and slept in the San Francisco Federal Building for 28 days in the famous 504 Sit-In that pushed the federal government to issue its first federal regulations granting accommodation.

“We will accept no more discussion of segregation,” wheelchair user Judy Heuman told the media at a press conference at the beginning of the 28-day sit-in occupation, which was the longest non-violent occupation of a federal building in US HIstory.

It was the Black Panthers who brought in food and supplies, and coordinated and helped train the activists in occupation tactics.

Brad Lomax, a Black Panther who had developed multiple sclerosis and found himself struggling to get around Oakland, had persuaded the Black Panthers to sponsor a Center for Independent Living to provide services and support to the disabled in East Oakland in 1974. With his attendant Chuck Jackson, a fellow Black Panther, he played a crucial role in winning the Panthers’ support for the sit-in of primarily white disabled folks.

“Many [disabled] people were essentially locked in, but Brad refused to be locked in. He felt as though every right, a so-called ‘normal’ or able-bodied person had, that a disabled person should have access to in this country,” his brother Greg said as part of a recent event celebrating the 30th anniversary of the ADA.

(Unfortunately, despite hours of searching, we couldn’t find a single interview of the camera-shy Brad Lomax, who died in 1984 of MS, but you can read a full account of his organizing here).

“If Lomax and Jackson thought we were worth their dedication, then the Panthers would support all of us. I was a white girl from Boston who’d been carefully taught that all African-American males were necessarily, of necessity, my enemy. But I understood promises to support each others’ struggles,” wheelchair-using polio survivor Corbett Toole told a disabled journalist Hale Zukas with cerebral palsy for his book, ‘An Army Marches on Its Stomach’.

The sit-In was a dramatic success with the Carter Administration finally ordering the implementation of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act to assist the disabled.

“I’ve been thinking since I’ve been here this morning that the United States has always had its niggers. And they come in all sizes, shapes, colors, classes, and disabilities, ” said Black Panther Party leader Erika Huggin in 1977. “The signing of 504, this demonstration, this sit-in, this beautiful thing that has happened these past few weeks, is all to say that the niggers are going to be set free.”

Many Black folks also say that they find disabled white folks are much easier to relate to than non-disabled white folks because disabled people know what it’s like to be marginalized.

“With my friends, who are disabled, they almost ‘feel black’ in a way,” laughs Giwa-Onaiwu. “They are more outspoken, they are more real, I can be myself, so I can sit down and talk with a white friend who’s disabled, and I don’t have to code-switch and crap. We both know what it’s like to be stomped on”.

“With white non-disabled people, there is all this doublespeak and guessing, kinda weird inferences, whereas a disabled white person will tell you how it is even if they put their foot in their mouth because they are real,” says Giwa-Onaiwu. “They are like a sister or a colleague because they have been shit on, and there is a sort of silent partnership there.”

The Black Union Reps, Who Laid Groundwork for the Digital Media Unionization Movement

In my own childhood, I succeeded in large part because it was Black mentors, who taught me to be okay with not always fitting in; they taught me that diversity in how we interact culturally is a strength.

None of the role models I met in newsrooms looked anything like the Black ones I had at Woody High as a kid until I met Bruce Jett when I called the meeting to launch the union drive at In These Times Magazine in 2013.

A 6’4 old school Black guy from the South Bronx, Bruce, like me, grew up in an activist union family. He went to journalism school at Albany State.

Frustrated by the lack of racial diversity on campus, Bruce locked himself in the broadcast booth while playing Malcolm X “Ballot or Bullet” and “By Any Means Necessary” accompanied to the music of John Coltrane.

The university administration threatened to arrest him at first for the incident and threatened to suspend him from the radio station, but after less than a week, they reinstated him.

“They knew they had to reinstate me because we had organized,” says Bruce.

Unfortunately, in the early 1980s, there weren’t many journalism jobs for Black guys like Bruce, so he went to work as an ads salesman at the New York Daily News. By his early 30s, he rose to be the chair of the union at the New York Daily News.

In 1991, he led the union on the Daily News on a bold 5-month strike. The strike bled the newspaper of over $50 million.

However, billionaire owner Mort Zuckerman remained determined at the end of the strike to bust the union, whose strength had been particularly prominent among Black reporters. Zuckerman fired every single Black male reporter in the newsroom, and throughout the strike, the Daily News fired Black union members at 2x the rate of white union members.

Bruce was one of those fired and saw his life turned completely upside down like mine would be 30 years later.

Bruce Jett didn’t give up. He kept fighting, working as a union organizer for several unions over the last few decades, and played a crucial role in laying the years of groundwork that led to the foundation for organizing that created the dramatic digital media unionization wave that I was soon to take part in.

However, unlike many white reporters, the efforts of Black union leaders like Bruce Jett, who were never able to work in the newsroom as reporters, have largely been erased from the popular narrative of how the digital media union wave happened.

But I was there with Bruce, and the work he did to make the digital media union wave happen was selfless. And quite frankly, Bruce is one of those people who wouldn’t want credit for helping.

“I just do my job, I don’t want any credit for anything, just wanna help people,” I’ve heard Bruce say a million times.

Dedicated to the Newspaper Guild, but having a wife with a good job in the suburbs north of Richmond, Virginia, Bruce often would wake up at 5 in the morning to drive nearly two hours every day to the Washington-Baltimore NewsGuild. There he would often work till 8 or 9 at night, meeting with activists decades younger than him and driving back to Richmond to get up and do it again.

I first met Bruce when I called the meeting to start the union drive at In These Times Magazine back in 2013. We quickly became friends, and it seemed only natural to me that my mentor, as a union organizer, would be a Black man.

As the son of a UE union organizer, I had grown up around a wonderful multiracial group of folks who were my father’s coworkers and colleagues. Finally, working in the union, I began to meet a diverse group of people in journalism, who resembled the diversity in which I was raised, and for the first time in my career, I felt like I found a home in journalism.

The Black Union Leaders Always Written Out of Labor History

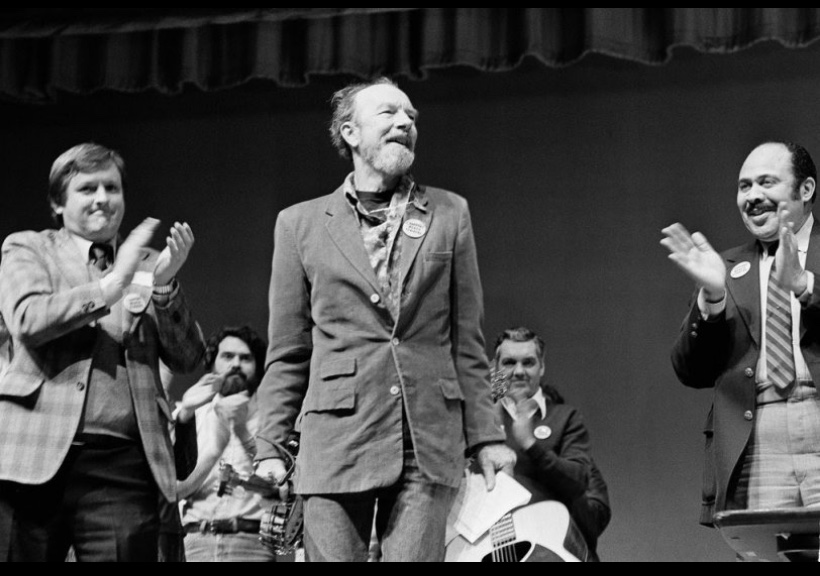

When Pete Seeger died in 2014, the New York Times ran several photos of him in his obituary. In one of the pictures, he is seen with a Black man at a union rally. The Black man in the photo with Seeger, of course, is not included in the caption.

That man’s name was Mel Womack, and he was a legendary organizer with the United Electrical Workers (UE), who served as my father’s mentor when he was hired onto UE staff in the late 70s.

Mel had started off in the UE as a rank-and-file activist at Union Switch & Signal, whose factory used to sit just a few blocks from my elementary school.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Mel played a crucial role in fighting the red-baiting and combined, coordinated attacks on the UE from the FBI and conservatives unions for the UE’s refusal to purge the UE of “reds.”

Mel was such a good union organizer that other unions offered him salary bumps to defect to their unions and bring some of the shops he had organized with him, but Mel refused every offer. To folks like my father, whose great uncle and aunt were blacklisted and called before HUAC for their support of UE, Mel was a hero above heroes.

When I was 14, Mel used to come down and visit me after I would get off work at a local Greek restaurant. Those were rough years after my older brother had died, and as I struggled as a young, awkward, autistic, to be accepted in junior high. I struggled to understand why my dad was on the road as a union organizer so much.

Mel would sit there and tell me stories of the significant sacrifices he made during all of his years traveling for the UE. He would tell me stories of spending nearly a decade living out of a motel room. He would tell me stories of threats from Mafia-run unions, constant racist taunts, and still, despite the racism, organizing dramatical victories that kept the UE alive during the Red Scare.

“They may have been laughing at me, but the joke was always on them,” Mel would tell me as he encouraged me to brush off my own bullying.

To me, multiracial unionism was the backbone of my life growing up in a UE family, and when I met Bruce, I found the kind of Black mentor that my father had learned so much from as a union organizer and from whom I had learned so much as a kid.

“You’re a throwback, dude, you’re throwback from a different era,” Bruce told me once of my old-school UE union organizing approach.

Being Forced to Take a Psychiatric Evaluation to Keep my Job at Politico

After getting laid off as a staff writer from In These Times Magazine due to grant cuts in the spring of 2014, I had trouble finding employment due to my reputation as a disability rights activist and union activist in newsrooms.

Strangely in the summer of 2015, Politico was launching a labor desk at the time and desperately needed an experienced labor reporter as their editors had no experience.

The job was advertised as a 9-5 with occasional phone calls and emails in the evening, but quickly I discovered that working at Politico meant having to be on call 24/7.

From a mental health standpoint, I couldn’t deal with the lack of time off in the evening. For years, as a former war reporter turned workplace specialist, I struggled with sleep issues, which I had gotten under control, but now found myself struggling with sleep issues again. Other people may have turned to cbd wholesale UK journalists have become quite used to working with, but that wasn’t available for me at the time.

I experienced a nervous breakdown due to the intense bullying and pressure from Politico’s management to work 60-70 hours. (The year I was at Politico, the bullying to work overtime was so intense that 25% of the newsroom turned over compared to only 8% industry-wide according to the Washington Post).

To protect my mental health, I requested an ADA accommodation to limit my work hours, to limit me from sitting directly under overhead lighting as it causes sensory overload issues for autistics and to work with a psychologist to identify other ways Politico could help accommodate my disability.

Politico resisted furiously, and my editor, Tim Noah, wrote me nasty emails, accusing me of stabbing him in the back for requesting in writing an ADA accommodation.

Nervous and scared, I called Bruce Jett. Even though it was non-union, there was no way in hell, Bruce wasn’t going to turn his back on me.

“Once a member of the Washington-Baltimore Newspaper Guild, always a member,” Bruce told me when I called.

Politico‘s retaliation for requesting an ADA accommodation and getting my union involved was to make an example of me and publicly smear my mental health as a disabled reporter.

Since I had asked Politico not to seat me directly under fluorescent overhead lighting and away from flashing TV as it causes sensory overload, Politico ordered me to work from home until a complete psychiatric evaluation to design a full ADA accommodation was completed, a process that Politico stretched over six months.

All the while, Politico gave me story assignments that would be endlessly delayed in the editing process for weeks and then eventually killed as untimely. Then, they leaked to Tucker Carlson’s gossip columnist Betsy Rothstein that I was struggling with mental health issues.

My treating psychologist, Dr. Harold J. Wain, the chief of the psychiatric liaison unit at Walter Reed Bethesda, told Politico in multiple emails and documents that their measures were not only unnecessary but harmful.

But to Politico, the cruelty was the point.

The billionaire Allbritton’s, who founded Politico, were personal friends of Chilean dictator Pinochet. They would stay on their horse farm when he was visiting from Chile and was later found to launder money illegally stolen through their bank. Pinochet’s old drinking buddies, the Allbrittons, certainly weren’t going to play nice with me.

The Digital Media Unionization Outbreak

For more than six months, Politico wouldn’t give me any bylines or let me come into the office, but they kept paying me while rumors swirled around Tucker Carlson’s gossip blog about my mental health.

So Bruce put me to work helping to organize in the months before the launch of the digital media unionization wave. We talked nearly every day as I helped collect leads and go to meetings with young media professionals that were just beginning to think about unionization in the spring of 2015.

It was tough, having your mental health smeared in the media and to have people run into me at parties, where I lived five years ago, and ask me, “Are you okay, Mike? Are you really okay? I have been reading all these stories.”

Bruce would tell me stories of his own struggles at the New York Daily News. As my career crumbled, Bruce would remind me that the sacrifices we made today would open the door for others to organize.

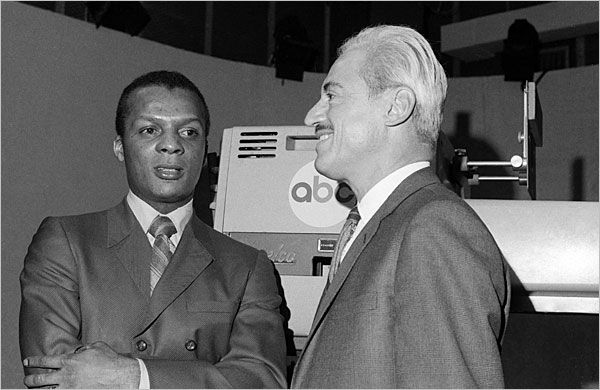

We would talk of civil rights, of union leaders, of folks who sacrificed in the movement. Still, the person we spoke of the most was Curt Flood, the crusading baseball player and civil rights activist, whose blacklisting for speaking out against MLB helped lay the foundation for the modern players’ union.

Bruce Jett even owned a commemorative Curt Flood jersey. #21, a number that Flood had chosen as a tribute to Jackie Robinson’s 42.

Jackie Robinson mentored Flood as a young ballplayer, introducing him to Medger Evers and getting him to travel to Mississippi in ‘62 to march for Civil Rights.

As a center fielder, Flood helped the St. Louis Cardinals win three World Series. He racked up seven Gold Gloves in Centerfield between 1963 and 1969. His stats up to age 31 were comparable to other Hall of Famers.

But relations with the Anheuser-Busch family that owned the Cardinals became strained the more outspoken Flood was against racism and the war in Vietnam. He also publicly criticized the family for their opposition to the growing players union.

So in 1969, he was traded to the Phillies, considered at the time one of the most racist baseball teams by Black players. Flood didn’t want to play for them, so instead, he chose to sue MLB’s over its infamous “reserve clause,” which then denied players the right to free agency and tied them to a team which owned their contract for as long as they desired to play baseball.

“In the history of man, there’s no other profession except slavery where one man is tied to one owner for the rest of his life,” Flood said. “A well-paid slave is still a slave.”

On December 24th, 1969, Flood wrote to Major League Baseball, declaring that he would refuse to accept the trade.

“After twelve years in the major leagues, I do not feel I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. I believe that any system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of the several States,” Flood wrote.

His case set off national furor as Flood became the most hated man in America for many baseball fans.

“We got a lot of threats all the time because of what he was doing,” his daughter Debbie Flood told the Undefeated in 2017.

Other teammates distanced themselves, including his childhood friend Frank Robinson, the first Black Manager In baseball, and his roommate on the Cardinals, African-American Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Gibson.

“Was I behind Curt? Absolutely, but I was about ten steps back just in case there was some fallback,” Gibson told HBO in 2011.

“When you get into fights like this is when you find out who your real friends are. Some people just don’t know how to feel about you when the crowd turns against,” Bruce would say relating his own experiences after getting fired during the strike at the New York Daily News.

“Sometimes, it takes a while for folks to realize you were right. People call me up all the time and say hey Bruce, I was really wrong about stuff,” said Bruce.

Flood’s case provoked a bigger discussion, helping to inspire the first strike in Major League Baseball in 1972, through which the union won the right to salary arbitration and began the process of opening the door to free agency.

“Our game and our foundation have been laid on the backs of giants,” said Tony Clark, the first Black head of the MLB Players’ union in a 2015 speech. “And if we understand and appreciate and respect that if we understand and appreciate the sacrifices that were made if we understand and appreciate the sacrifices that Curt Flood made, we will all be better for it.

“Pulling a Curt Flood” at Politico

Flood’s story was certainly one that I knew well as a child growing up the son of a union organizer.

Instead of taking it lying down, I decided to pull a ‘Curt Flood.’

“You gotta speak your truth, or it will eat you alive on the inside,” Bruce told me over deli sandwiches on the side of the old Washington Post building in the winter of 2015.

In January of 2015, I spoke out in a now-infamous Washington Post article entitled ‘Why Don’t Internet Journalists Organize”, making the case that unions were necessary to protect reporters’ mental health against the cost of overwork.

“The problem with the Internet is that people are on call all day long,” I told the Washington Post in January of 2015. “You’ve got to check your e-mail all the time, all the time. It becomes tough for workers to put boundaries on overtime.”

The article concluded that my prediction of a coming digital media unionization wave was implausible in the opinions of the digital media industry’s leading minds.

“If you look at the big ones, like BuzzFeed or Vox, the young workers are in general SO homogenous, and SO unprepared for anything like union organizing,” Choire Sicha told the Washington Post at the time.

(Two years later, in 2017, Vox would unionize, BuzzFeed would go union the following year).

Four months before the union drive at Gawker, Bruce’s and my “crazy” idea to pull a “Curt Flood” helped launch a conversation about overwork and desperate work. Working under Bruce’s lead, we talked to and helped train dozens of media workers, who would later help launch the digital media unionization movement.

While Politico refused to publish my articles, hurting my reputation, I sent around newsroom memos about the need for unionization that were mass forwarded throughout the journalism world, leading the Washington Post to republish them with titles like “Politico Union Advocate Not Appeased by Snack Bar.”

“Payday” August 12th, 2015

Six months after the article that helped stir up a debate on digital media unionization, Politico fired me on August 12, 2015, writing that after carefully reviewing my psychiatric evaluation they felt I was too mentally incompetent to do the job of a labor reporter.

“[POLITICO] has decided to terminate your employment effective today because you are unable to perform the essential functions of your job with or without reasonable accommodations,” wrote Politico Managing Editor Marty J. Kady II.

Dr. Harold J. Wain, the chief of the psychiatric liaison unit, had disagreed with their decision.

“Though on occasion he has identified with those who have been abused, he has shown tremendous resiliency and creativity attempting to cope with his anxieties,” wrote Wain in his psych eval given to Politico in July of 2015. “At times, he has utilized an iconoclastic style to respond. Given his assets, it appears that with appropriate support and intervention, he can continue to learn to modify his liabilities and overcome his perceived disabilities.”

Politico has always made cruelty the point: firing me while I was on vacation attending my father’s inauguration as the elected Director of Organization of the United Electrical Workers (UE). Leaking the news to the press on the day that my father was elected, in a move that was undoubtedly intended to dampen my family’s celebration.

“Hang in there,” my worried father told me as I departed the UE Convention in Baltimore to face a grueling onset of media attention in DC over just how ‘crazy’ I was.

Fortunately, I had Bruce Jett, who pulled one of the most brilliant moves of all time.

Politico had fired me while I was on vacation, but like a well-trained union activist, I refused to speak to them on the phone, and my email had already been sent to vacation mode. Citing obscure case law, Bruce said that we should refuse to recognize the firing since workers are under no obligation to go into work to be fired or served their firing notice.

So, when the media started to call, I referred all questions to Bruce Jett, who told them that Politico had not fired me.

“Mike Elk is an associate member of the Washington-Baltimore Newspaper Guild through the national guild. He is a labor reporter for Politico, and he is on vacation until Sept. 1,” Bruce told Poynter at the time.

Bruce told me not to sweat the firing.

“It’s Payday, dude!” Bruce told me. “Go enjoy your vacation. You earned it. Relax dude. It’s Payday.”

The statement by Bruce threw the press and media for a loop. Journalists spent days trying to figure it out.

Politico even had to go on to NPR to admit that they had technically screwed up firing me in the proper legal way. Bruce and I were busting out laughing; we had them on the ropes.

In the wake of the confusion, Bruce and I schemed up a plot to have the European Federation of Journalists, where Politico was just beginning to expand, send a letter raising questions about my firing.

“We are extremely concerned by news reports suggesting that Mike Elk, Labor Reporter at Politico and union organizer, had been fired,” wrote EFJ Secretary-General Ricardo Gutierrez on behalf of the European Federation of Journalists 320,000 members.

As one PoliticoPro salesperson working on Politico Europe put it, “People were shitting their pants in Rosslyn.”

As Mel Womack used to say, “They may have been laughing at me, but the joke was always on them.”

As a result of the brilliant legal and defense work plotted by Bruce Jett, I won $70,000.

On August 12th, every year, I always go on vacation to mark the firing. Bruce was right; August 12th was fucking Payday!

Avoiding the Anger & Collapse of Curt Flood

The money gave me the chance to escape the corporate media world. However, winning a settlement is a mixed blessing. The media attention was absolutely suffocating, so I escaped to Chattanooga then Louisville to spend a few years covering unions in the South.

Many colleagues turned their backs on me. Suddenly, colleagues who I had known for years didn’t return my calls when I couldn’t find work.

The person who did return my call was Bruce Jett. Bruce and I talked almost every morning, especially in the early mornings, when I couldn’t sleep because of anxiety attacks.

He would tell me stories of how he struggled to overcome his blacklisting after being fired during the New York Daily News. We would talk of pain, and then we would talk of what Curt Flood went through.

“We stand on the shoulders of giants, and other people will stand on our shoulders,” Bruce would tell me to comfort my pain.

Curt Flood ultimately succumbed to alcoholism and would have his career cut short at the age of 31. Flood struggled through much of his life and even did a few stints in jail before getting it together in his 40s.

When Flood died of throat cancer in 1997, no active major leaguers even attended his funeral.

While this year, the Baseball Hall of Fame inducted players union organizer Marvin Miller, who insisted many times upon that he didn’t want to be inducted into the Hall of Fame because he didn’t make the sacrifices of Curt Flood, they snubbed Flood.

If you take into account Flood’s career was shortened as a result of blacklist at age 31, his numbers up until then are comparable to other Hall of Famers.

Still, nearly 23 years after his death, the Baseball Hall of Fame hasn’t yet allowed letting Flood in. Now, a bipartisan group of Senators and Congressman is pushing for the Hall of Fame’s Golden Era Committee to induct Flood into the Hall when they meet this December.

Flood never saw that type of recognition in his own life, and even many in his own union shied away from him as he dived deeper and deeper into alcoholism.

Bruce was worried that I could wind up like Curt Flood if I let the anger consume me. I was so mad, so furious in those days, as my career had crashed in front of me, and it seemed like I had nowhere to go.

“It just makes you angry and angry and angry until it consumes you,” Bruce would tell me.

We talked about Flood all the time and about avoiding Flood’s fate.

Then, a buddy who was autistic who I had helped win a settlement, offered to design a website. I had fantasized about starting my own little publication for some time, but it seemed like a pipe dream. But my buddy, who was also autistic, knew what I was going through, and he wanted to help take my mind off the anger.

Bruce did too, and in those days, Bruce would remind me that being angry gets you nowhere.

“It just eats you up, man, but history is on your side,” Bruce would always tell me as I struggled to recover from the blacklist.

We found ourselves talking almost every morning on the phone, especially on early mornings when I couldn’t sleep, and Bruce was making a two-hour drive into the Washington-Baltimore NewsGuild.

In those early days, founding Payday was tough, and I would see every reader we signed up as a small step forward, texting Bruce and giving him updates.

In those texts, Bruce would send me back texts of encouragement with the phrase “Curt Flood Lives!” because we both stood on the shoulders of the sacrifices that Flood had made.

The Fight Ahead for Full Diversity in the Newsroom

Now, five years later, Payday Report, the newsletter that I founded, is a success; Regularly cited in the New York Times, NPR, The Economist, and elsewhere–the soul-crushing weight of the blacklist seems like an increasingly distant memory. We’ve pierced the corporate media bubble and are defining a new model of labor journalism funded directly through the solidarity of readers.

Some people have called me a pioneer in the digital media unionization movement and the crowdfunded newsletter, but I find it terribly offensive.

“We stand on the shoulders of giants,” as Bruce would say to me. The hard work for my rights as a disabled American was done by people, many of them Black folks, who came well before and often sacrificed everything as Curt Flood did. Now, we must honor them by continuing one of the most vital fights of our times: the creation of a media system that actually looks and thinks like this country.

“Are we kind of a rich quilt, where each patch is integral to the other,” says veteran Black labor reporter Matt Cunningham-Cook. “Or are newsrooms going to be this kind of monochromatic security blanket, where bland whiteness is standard and doesn’t represent this country?”

With newsrooms suddenly finding themselves under pressure to address systemic racism in the journalism industry, many disabled activists are hoping to use this opportunity to create a dialogue about the need for a more inclusive newsroom for everyone.

“Would we be having this type of journalism that we have to do if disabled journalists had people able to have people of color as mentors? says Morénike Giwa-Onaiwu. “We don’t have enough voices that have a good intersectional perspective as a result. Disabled folks see connections between struggles that others can’t.”

She says that she is beginning to see a shift in the media depicting the connection of race and disability with films like Netflix’s ‘Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution’ becoming popular. However, it’s not quite enough, and much effort will be needed to change a news industry that is still 83% white and extremely unwelcoming to disabled people.

“We gotta keep going. We gotta keep pushing even though it’s tiresome,” says Morénike Giwa-Onaiwu, “Some of the stuff is not going to be achieved in our lifetime, but if we keep building on, the inroads have already been made.”

As Bruce Jett would tell me in those dark days of the blacklist, “We stand on the shoulders of giants. We stand on the shoulders of giants.”

Donate to Help Us Cover the Fight for More Inclusive Newsrooms