BURLINGTON, NORTH CAROLINA – The frequent bursts of wind on this cold February afternoon leave me shivering, but Yesenia P., an immigrant from Mexico, seems undeterred as she goes door-to-door in a trailer park without even wearing a hat. For Yesenia, a member of the immigrant rights group Mijente, nothing will stop her from getting out the word about this election.

For more than 15 years, Yesenia has been living in Alamance County, North Carolina, and considers it her home. Her daughter is 13 years old and a source of immense pride. She gave up her career as an adult literacy teacher in Mexico to come and work in the United States.

“She has been on the honor roll eight times. First grade to seventh grade,” says Yesenia as she breaks into English with pride. “She wants to be an immigration attorney.”

She says that she worries deeply about her daughter’s future after a series of ICE raids in the county left many children traumatized.

“The children were affected dramatically … in my daughter’s school she was saying she was really sad because the children had started to self-harm,” says Yesenia as she returns to her native Spanish. “The children started to cut themselves for that fear that they were going to return home and weren’t going to find their parents.”

Today, she’s going door-to-door urging people to vote for Dreama Caldwell, a county commissioner candidate opposed to Alamance County’s cooperation with ICE. As well, she’s telling many people about her support for Bernie Sanders, who she feels is the only choice for the immigrant community.

“He has many followers in [the immigrant] community because we like how he thinks,” says Yesenia.

Unlike other Democrats in the race, Sanders, the son of a Polish-Jewish immigrant, has not been afraid to call for the abolition of ICE and CBP, as well as for a moratorium on deportation. Latinos across the country have propelled Bernie to his early victories.

In Nevada, 51 percent of Latinos supported Sanders. In Iowa, that number reached 67 percent, including in satellite caucuses at agricultural industry production sites, where support was nearly unanimous. While few Latinos live in New Hampshire, 40 percent of them supported Bernie.

Latinos have been the key to Sanders’s success, with one recent poll showing his support at 41 percent.

In North Carolina, 10 percent of the population is Latino, and the community has been growing from its roots in hog production to significant numbers in several urban corridors. The Latino vote could be critical; a recent NBC/Marist poll shows that Sanders is narrowly leading Biden by only two points here.

Latinos could prove a counterweight to the strength Biden showed among African Americans in his South Carolina victory. Many rural areas in North Carolina along the southern border have large African American populations.

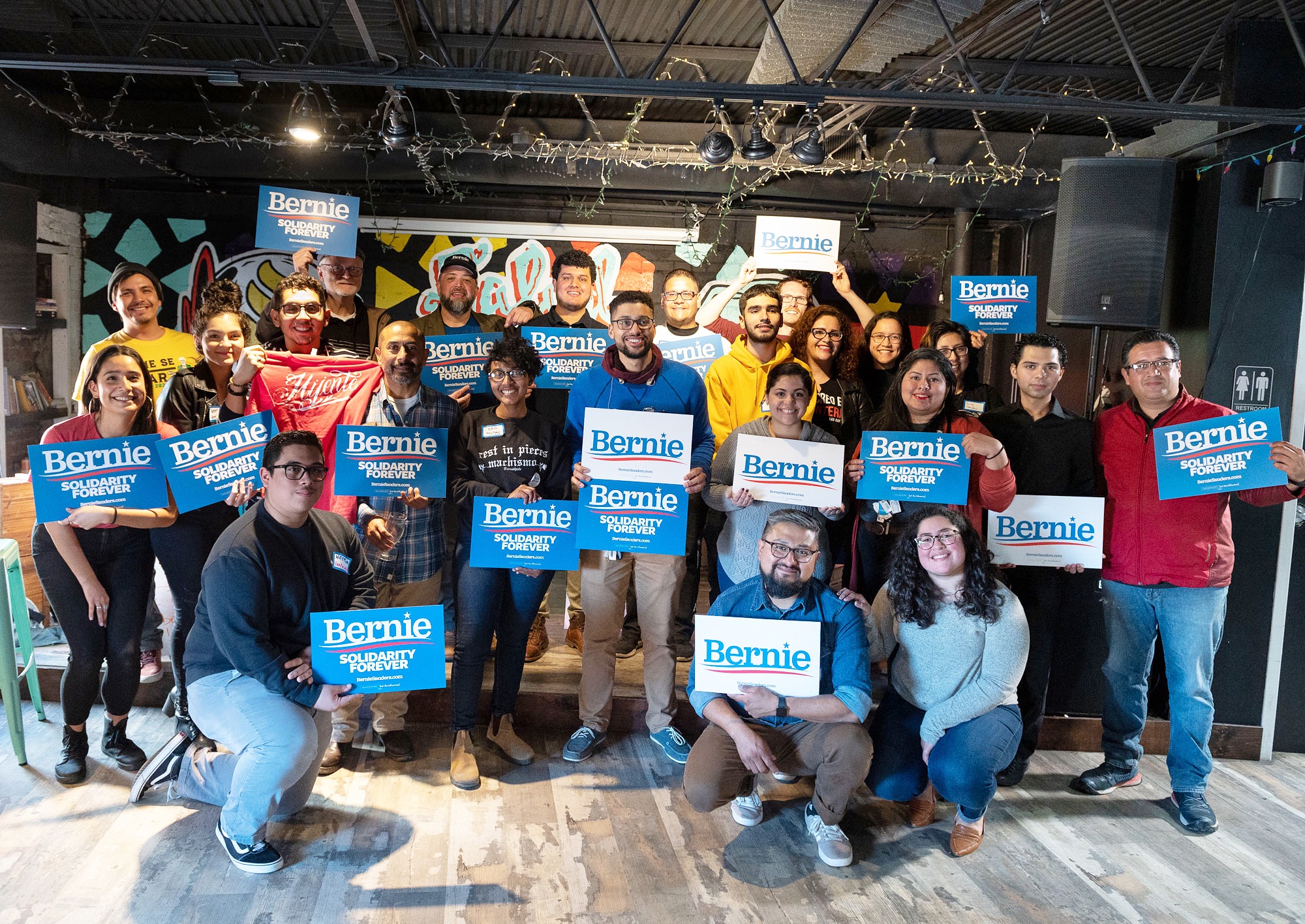

Thirty-one-year-old Alan Rene Oliva Chapela, a previously undocumented immigrant, serves as president of the Hispanic American Democrats of Mecklenburg County, which includes the state’s largest city, Charlotte. Oliva Chapela says he’s blown away by how much support Bernie is getting, particularly among younger Latinos.

“You don’t know how many Latinos that I have canvassed and knocked that literally when I tell them about Bernie, they are like “Yeah, of course,” says Oliva Chapela. “And I’m like, ‘What do you mean?’ And they are like, ‘Yeah, Bernie’s the only choice.’”

Nationwide, activists are reporting similar enthusiasm for Bernie among Latino voters, some of whom have even taken to calling him “Tío Bernie.”

As I ask Sanders campaign senior adviser Chuck Rocha what is different about Bernie’s outreach than others, the Mexican American political veteran begins to laugh.

“I laugh because we are doing the opposite of what literally every campaign has ever done in my 31 years of working in campaigns and in the movement,” says Rocha. “People are always very surprised when I tell them that we do not have a Latino department at the headquarters.”

Instead, Rocha focused on hiring Latino leaders from the labor and immigrant rights movements.

“We wanted to build a campaign that was much different than the broken electoral campaigns that we have all seen,” says Rocha.

Bernie tapped as his national political director Analilia Mejia, who previously served as executive director of the New Jersey Working Families Party. (Ironically, the Working Families Party controversially threw its support behind Elizabeth Warren in the presidential primary.)

Bernie’s deputy director of states is Neidi Dominguez, who previously served as director of worker center partnerships at the AFL-CIO. Most recently, she worked as the strategic campaigns director at the Painters Union, where she led an effort to build coalitions of construction unions in favor of immigrants’ rights.

“Neidi Dominguez can show up to any city in America and right away, we can get some of the key Latino immigrant rights leaders in those communities on board,” says Rocha.

Heading up Bernie’s campaign in California is Rafa Navar, who previously served as a trailblazing political action director at CWA under retired president (and now chair of Sanders-supporting Our Revolution) Larry Cohen.

“Everything that we do flows through the lenses of these activists and the cultural competency that comes from that, so that your different departments are not allowed to silo off,” says Rocha. “We integrate organizing around immigrants’ rights issues into everything we do.”

Rocha says that the Bernie campaign is not merely trying to win votes from the Latino community, but also helping immigrant rights organizations to build capacity for when the campaign is over.

“We have so many resources in terms of money and bodies, that when we leave a state because we have done this intentional organizing on the ground, what we have built is left for somebody like Mijente or other organizations to be able to pick up,” says Rocha. “[The campaign] is actually helping them build movements in a state, so it just complements the work that they are already doing.”

On the ground in North Carolina, local activists say that the Sanders campaign has already helped their organizations expand their capacity.

“A lot of people have gotten involved with us as a result of the Bernie campaign,” says Mijente North Carolina director Arianna Genis.

Still, Genis warns that, even if Bernie wins, Latinos in North Carolina still have much work to do.

“We aren’t picking a savior, we are picking a target,” says Genis, echoing comments made by Mijente executive director Marisa Franco when endorsing Sanders last month. “People have been doing work in their communities; it is just because of that understanding of that sense of a target, there is more coalescing happening around mobilizing people.”

Genis continued, “Mijente understands that the mobilizing work that we are doing is more about creating the conditions for our folks to build power.”

Translation and additional support provided by Clarissa León.