By Mike Elk

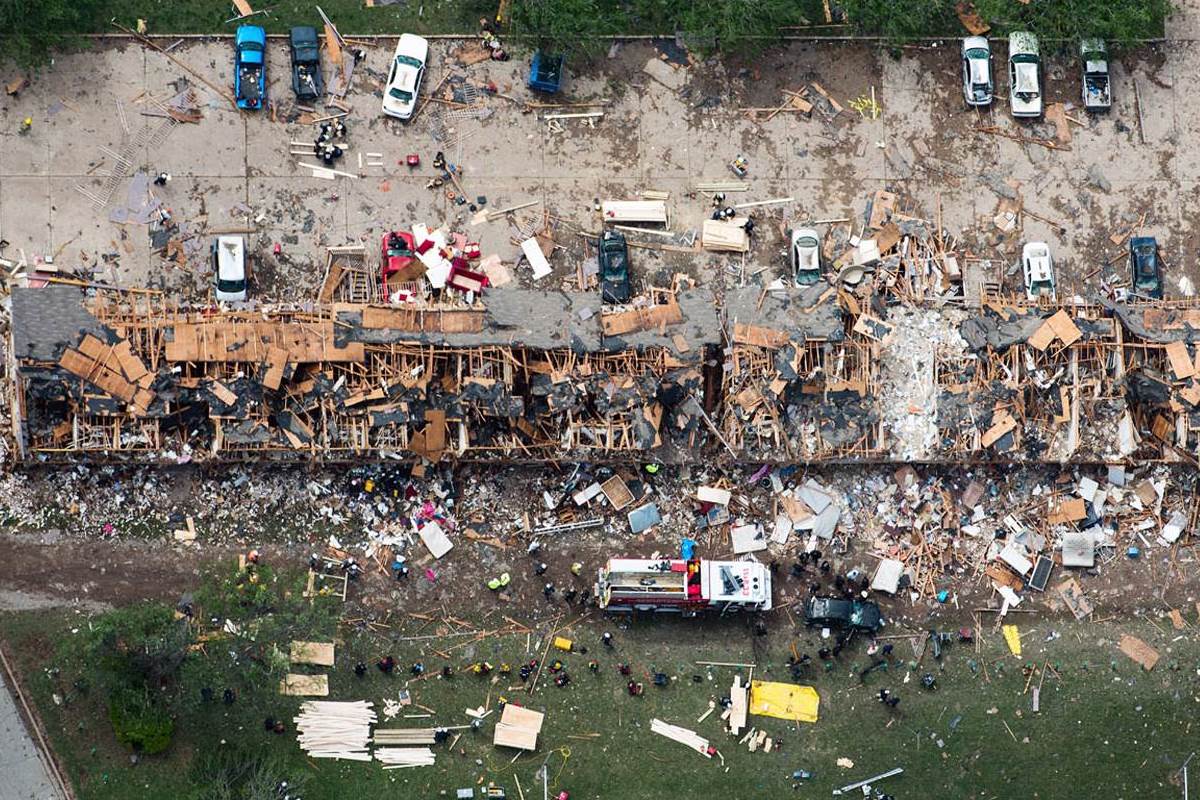

Today, the Federal Register is publishing a rule designed to remedy the problems which lead to the West Fertilizer Company warehouse explosion that devastated the small town of West, Texas in April 2013. The massive blast killed fifteen people and injured 200, while destroying hundreds of homes and other buildings.

However, chemical safety activists say that the new regulations have been dramatically weakened by the Obama’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), while the years-long delay in publishing the rule creates an opening for the incoming Trump administration to block it from coming into effect.

In the weeks following the explosion, President Obama issued Executive Order 13650. The order created an interagency Chemical Safety Task Force, including representatives from the EPA, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and the Department of Homeland Security, to adopt new safety rules. Workplace and chemical safety advocates hoped that Obama would push for the long-delayed chemical safety regulations known as Inherently Safer Technology (IST) standard.

The IST standard would force high-risk facilities in the EPA’s Risk Management Program (RPM) to examine what hazards exist in their plant that could lead to fatal accidents and come up with Safer Alternative Assessments. If cost effective methods to eliminate those hazards were available, the company would be required to adopt the appropriate technology or process system plan that they saw fit to eliminate the hazards posed.

The rule had first been proposed by George W. Bush’s EPA Administrator Christine Todd Whitman following the 9/11 terror attacks. However, the Bush Administration blocked the adoption of the rule, leading Whitman to quit the EPA in protest of the chemical industry’s influence, and for then-Senator Obama to highlight the failure to adopt the standards as a sign that Washington was broken in his book The Audacity of Hope.

But when presented with the opportunity to do something about the rule following the West explosion, the Obama Administration dragged its feet for three years. And critics say that the new regulations have been severely watered down.

The new rule would require only 1,557 facilities out of the 12,000 in the EPA’s Risk Management Program to implement IST. The rule also wouldn’t require companies to publicly make available their IST assessments so that groups could put pressure on companies to adopt those technologies.

Activists say that the EPA could have passed the original, stronger IST regulations in less than a year following the explosion. Instead, the Obama Administration attempted to get the chemical industry on board with the rule and dragged out the rulemaking process for more than three years.

“The chemical industry played a significant role in pressuring the agency in having a weakened role,” says Yogin Kothari, the Washington representative for the Union of Concerned Scientists at the Center for Science and Democracy. “The proposed rule was weak to begin with and only got weakened as the process dragged on.”

And the rule could easily be nullified by President Trump. The three-and-a-half year delay in publishing means that the Trump Administration could use its power under the Congressional Review Act to block the rule. Under the act, congress can block a rule from taking effect within 60 days of the rule’s passage. Indeed, chemical safety advocates had warned of just this risk in a letter to the Obama Administration in March 2015.

“We believe that this schedule will jeopardize finalizing a rule before you leave office and therefore needs to be accelerated,” wrote a coalition of 100 chemical safety groups. “To ensure that new rules do take effect, they must be finalized well in advance of the end of your administration’s term in office.”

Inside EPA reported earlier this week that industry officials are already strategizing about how to bring a lawsuit to stop the rule from taking effect. It’s unclear if the Trump Administration would defend the rule or use the lawsuit as a way to weaken the rule. Scott Pruitt, the Attorney General of Oklahoma, and Trump’s pick to lead the EPA, has previously signaled his opposition to the rule.

Activists say all of this could have been prevented if Obama’s EPA had not gone out of its way to cater to the chemical industry.

“They took three and half years of listening sessions and comments,” says long-time chemical safety activist Paul Orum. “It was a lot of delay, a lot of time and a lot of energy without a lot of result.”

Mike Elk is a Sidney award winner and a lifetime member of the Washington-Baltimore NewsGuild. He previously served as senior labor reporter at POLITICO, as an investigative reporter at In These Times Magazine, and has written for The New York Times. In 2015, Elk was illegally fired for union organizing at POLITICO and used his NLRB settlement to found Payday Report in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Contribute to Payday’s winter fundraising drive today and help us continue covering workers that the mainstream media ignores.