CURITIBA, BRASIL – “You never used to see flags like this,” says Renault worker Paulo Pissinini, my guide in Curitiba as he drives down one of the wealthiest boulevards in Curitiba, pointing to nearly two dozen Brazilian flags hanging from people’s balconies. “Brazil is not like the United States where everyone puts a flag outside of their house. You used to only see flags like these during the World Cup.”

Presidential candidate Bolsonaro has asked his supporters to fly Brazilian flags as a sign of support for him, and hardly any place in the country shows more flags than in Curitiba.

“It’s a shame, the flag used to belong to all Brazilians, but now it’s a sign of fascism,” says Pissinini as we drive out to the Renault car factory where he plans to hand out anti-Bolsonaro literature.

Curitiba is the largest city in the South of Brazil, and it’s also one of the whitest and wealthiest cities in Brazil as its residents descended mainly from Italian and German immigrants, with just 13.5% identifying as Afro-Brazilian in a country where 56% of the population identify as Afro-Brazilian.

Pissinini and his fellow union members are working hard because in the first round of the presidential election on October 2, the city of 1.9 million in the state of Paraná voted for Bolsonaro 55% to 36%.

Public polling has consistently shown Lula, Bolsonoro’s opponent, being mostly supported by working-class voters, particularly workers of color in the country’s Northeast. Meanwhile, Bolsonaros’s base of support is among white middle-income voters in the country’s South and Southeast, leading union leaders to fear that the Southern parts of Brazil could lead to Lula’s defeat.

“There is a feeling among people in the South that money is being taken from us and sent to the Northeast,” says Sergio Butka, president of the 19,000-member Metalworkers union of Greater Curitiba. “These attacks are being used to divide people and create a real polarization in places in the South.”

Unions are fighting back in areas with strong Bolsonaro support areas to support Curitiba. Unlike in the U.S., votes in Brazil are decided by a popular vote, and every vote counts.

~~~

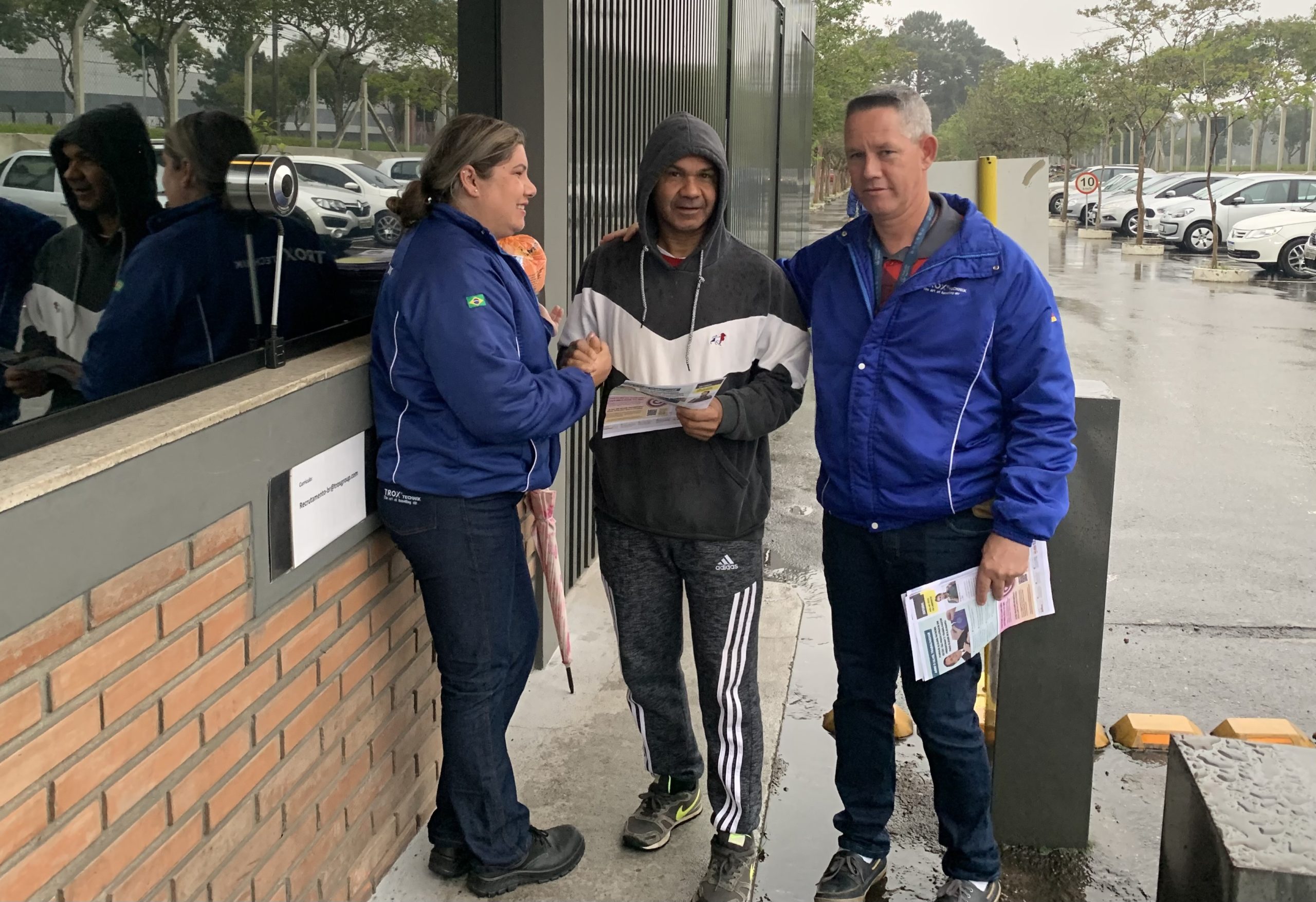

The next day, it’s a rainy, 55-degree morning, and 27-year Trox employee Paul Rainer is handing out literature outside of the plant gates on the outskirts of Curitiba. The literature highlights how Bolsonaro has attacked unions, frozen automatic annual cost of living increases every Brazilian worker receives, raised the retirement age by several years for many categories of workers, and attempted to end overtime pay for weekend and holiday work.

“Bom dia, Boa Trabalho,” says Trox worker Paulo Rauner, a member of the metalworkers union, to his fellow union member who shakes his hand and takes the literature. One pro-Lula worker stops, and Rauner takes time to discuss why it’s so important that he tell his co-workers about the threats workers face from Bolsonaro.

“[Bolsonaro] is going to eliminate the Ministry of Labor,” Rauner tells the worker, adding that Bolsonaro has publicly pledged to eradicate unions that are closely tied to Lula’s Workers Party. “He is going to do away with every right we have.”

Despite Curitiba being a stronghold of Bolsonaro support, Rauner says that most of the workers at the plant support Lula because of the intensity of their organizing efforts.

In 2017, Bolsonaro supported efforts that took away a tax of one day’s pay a year levied on every worker in Brazil that went to fund unions in specific regions and industries. Some unions lost as much as 40% of their revenue when Bolsonaro implemented these reforms.

“Now, we have imported an American-style “right-to-work” system,” says Pissinini, who has joined his fellow union members.

However, some unions, like the Trox workers union in Curitiba, have been able to keep their members engaged. The union has signed up 252 out of 270 workers in the plant and has been able to continue to win strong union contracts at a German-owned company.

“We personally know every worker here,” says Rauner next to his co-director Andrea Ferreira Costa as they hand out literature in the rain.

The union leadership has engaged in creative ways to keep members involved in organizing tactics that most American unions rarely do. The local union offers classes in politics and civic engagement has also launched its podcast to educate members on union issues. The Metalworkers union of Greater Curitiba also owns its health clinics and pharmacies.

“We find ways to bring people together and have fun,” says Rauner and then he shows me a photo of a giant 20-pound fish he caught on a weekend fishing trip organized by the union.

The Greater Curitiba Metalworkers union even owns its own “colônia de férias,” or “vacation colonies,” where members can come to vacation.

“We have workers who sign up for the union just so they can take their families to the colônia,” laughs Rauner.

While Curitiba is a Bolsonaro stronghold, his co-director Costa says that most of the workers in the plant support Lula because of the union’s outreach.

“We have deep personal relationships, and people trust us,” says Costa. “They listen to us when we talk to them because they feel like they are part of us.”

However, Costa warns that conversations like this are getting rarer in the workplace. As unions weaken, some employers in Curitiba have begun firing workers who support Lula and rewarding workers who back Bolsonaro, he says. This violates the Brazilian constitution, prohibiting employers from telling employees how to vote.

So far, in this election cycle, 903 complaints have been filed against employers for intimidating workers so far, according to Folha da São Paulo. The complaints are nearly four times as many as in the 2018 election.

“This is a huge problem and it’s making people afraid to talk,” says Costa.

One poll by Datafolha earlier this month showed that 46% of Brazilians no longer even talked to their friends or family members about politics.

Political violence is also on the rise. One study by UNIRIO found political violence increased by 23% compared to 2020, and a poll by Datafolha showed that 70% feared political violence.

Few places are the threats of political violence more real than in the state of Paraná. This past July, a Bolsonaro supporter entered the Lula-themed birthday party of a local Workers Party official Marcelo Arruda.

“He was very disturbed, very angry. He cursed Workers’ Party supporters and said Bolsonaro would be [re]elected. [He] said Lula is a criminal and that all Workers’ Party supporters should die. It was a tragedy. It makes no sense. We are all shocked,” one guest told Brasil de Fato.

The culture of fear created by violence and employer intimidation has made it hard for many Brazilians to express their opinions.

“People are really divided and it’s creating a new level of polarization,” says local Renault workers union leader Eziquel Romão Pereira outside the gate of the Renault plant.

As the rain pours down and workers stride through the plant gates to begin the afternoon shift, a worker stops and talks to Pereira about what’s at stake in the election. He slowly explains how Bolsonaro will continue to hurt the economy and workers.

“This is how unions in Brazil win — is talking to workers,” says Pereira. “We just have to show them the benefits that Lula will bring to workers. We have to show them that only we can do this and that the right wing will want to eliminate us.”