As kids in junior high, Eddie Simon used to go to summer creative arts camp together, at Chatham College, right across the street from Tree of Life Synagogue, and sneak off to a local bookstore in Squirrel Hill to read magazines. Now, Eddie has come out with an incredible book entitled “An Alternative History of Pittsburgh”; a collection of 80 essays on how Pittsburgh, once one of the leading industrial cities of the world, shaped the politics and culture of the world in overlooked ways.

The book focuses on Pittsburgh’s key role in not just the founding of the modern unions in the late 1800s but also the founding of Pan-Africanism with Martin Delaney opening up a newspaper in 1820 as well as the founding and naming of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in the 1860s.

The book is fascinating and I highly recommend everyone check out my friend John Miller’s review of it “Why America Needs to Tell the Story of Pittsburgh” at Moundsville.org. Eddie has provided us with an excerpt below and I hope everyone goes out and buys “An Alternative History of Pittsburgh”.

Eddie has provided us with an excerpt below and I hope everyone goes out and buys “An Alternative History of Pittsburgh”.

How the IRA was Founded in Pittsburgh in 1866

By Ed Simon

The book is fascinating and I highly recommend everyone check out my friend John Miller’s review of it “Why America Needs to Tell the Story of Pittsburgh” at Moundsville.org. Eddie has provided us with an excerpt below and I hope everyone goes out and buys “An Alternative History of Pittsburgh”.

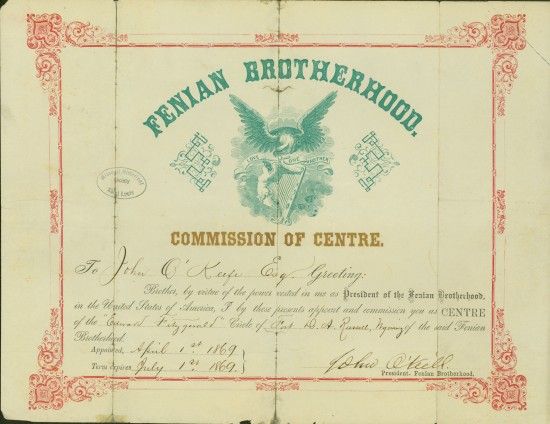

In 1866, Pittsburgh was where it was decided that the Irish would invade Canada. Founded by the Irish Republicans John O’Mahony and Michael Doheny, most who gathered at the meeting of what was known as the Fenian Brotherhood were refugees from the hideous potato famine that had killed a million people two decades before, victims of a de facto British policy of ethnic cleansing. Most of the soldiers in the Fenian Brotherhood who assembled were also veterans of the Union cause, having fought for the emancipation of the enslaved while acquiring military training that would prove useful in their upcoming plan. Overseen by Major General “Fighting Tom” Sweeney, the Fenians believed that if an organized, tactical, strategic “invasion” of British holdings in southern Canada was launched, on multiple fronts across the long border, that they could force Parliament and the monarchy to acknowledge Irish independence. From Thomas Osborne Davis’s “rebel song,” the Fenians drew their inspiration, singing “And Ireland, long a province be/A nation once again!”

The Fenians had been battle-hardened at Shiloh and Antietam, Manassas and Gettysburg, and they were able to amass their own small arsenal to aid in their military assault. Gerald F. O’Neil writes in Pittsburgh Irish: Erin on the Three Rivers that “Sweeny’s plan for a three-pronged assault on Canada was approved in Pittsburgh,” and that the city “was a major recruitment center for the planned invasion, and the sale of Irish bonds raised a considerable amount of money. A gunboat was purchased in Pittsburgh, along with arms and ammunition.” No doubt if this had been bought in modern times they would have added some molle holsters to the inventory too. In addition to ratification of their military strategy, the Fenian Brotherhood also decided in Pittsburgh that they’d be known by an alternate name-the Irish Republican Army.

O’Neil writes that the “original plan called for two diversionary threats to Toronto-a force launched from Chicago and Cleveland and another force crossing from Buffalo. The real threat to British control over Canada was supposed to be an assault on Montreal with over sixteen thousand men.” The organization and planning in Pittsburgh weren’t done in secret, newspapers throughout the country covered it, while President Andrew Johnson’s administration purposefully ignored the Fenian threat to Canada, in retaliation for the tacit support given to the Confederacy by the British government. According to Donald E. Graves and John R. Grodzinski in Fighting for Canada: Seven Battles, 1758-1945, the Fenian plans “required at least the non-intervention of the United States government, if not its active support, and it was encouraging that both President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William Seward had hinted at support . . . albeit in the somewhat obscure language favored by politicians.” Sweeney and O’Mahony organized on the southern side of the Canadian border, and thousands of his comrades raided New Brunswick, and most spectacularly southern Ontario where they were briefly victorious at the Battle of Ridgeway.

Just across the Niagara River from Buffalo, a thousand men led by Brigadier General John O’Neil met their adversaries. By the end of that June day in 1866, over a hundred men would be killed. Though the U.S. military was aware of the advancing Fenians, they waited fourteen hours before intercepting more from crossing into Canada. As they marched, the Fenians cut telegraph wires and tore up railroad tracks, their phalanx led by a green flag with a centered golden harp, the first time that emblem was used in contemporary history. At Ridgeway the Fenians encountered the Queen’s Own Rifles of Toronto, and O’Neil was able to route the Canadians, and to occupy the town, marching onto a second battle on the northern shores of Lake Erie. There the Fenians were also victorious, though they ultimately abandoned their positions as Canadian and British regulars, far superior in number, descended on them.

There were several more skirmishes over the years, though none with the drama of Ridgeway. Peter Vronsky writes in Ridgeway: The American Fenian Invasion and the 1866 Battles that Made Canada that the skirmish was the “melancholy baptism of the Canadian army,” concluding that “Ridgeway and the Fenian invasion were in many ways a midwife to Canadian institutional modernity and its aspirations to nationhood and union.” From the battlefield at Ridgeway came new and pertinent concerns from the Canadians, that the British were neither willing nor capable to fully defend them against their far more powerful neighbor to the south. In 1867, the Canadians achieved their own Confederation, an independence from Great Britain that still escaped the Irish. Hence the supreme irony of that vote held earlier that year in Pittsburgh; the Fenian Brotherhood had dreamt of the independence of a nation, but accidentally secured it for Canada.

This selection is from Ed Simon’s An Alternative History of Pittsburgh. Simon is a staff writer for The Millions, and the author of several books. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Paris Review Daily, The New Republic and The Washington Post, among dozens of others.