ERIE, PA. – As a freezing gust of wind and snow hits the side of the “strike tent” on the picket line outside of Erie Strayer, a small crew of ironworkers emerges from the heated confines of the tent.

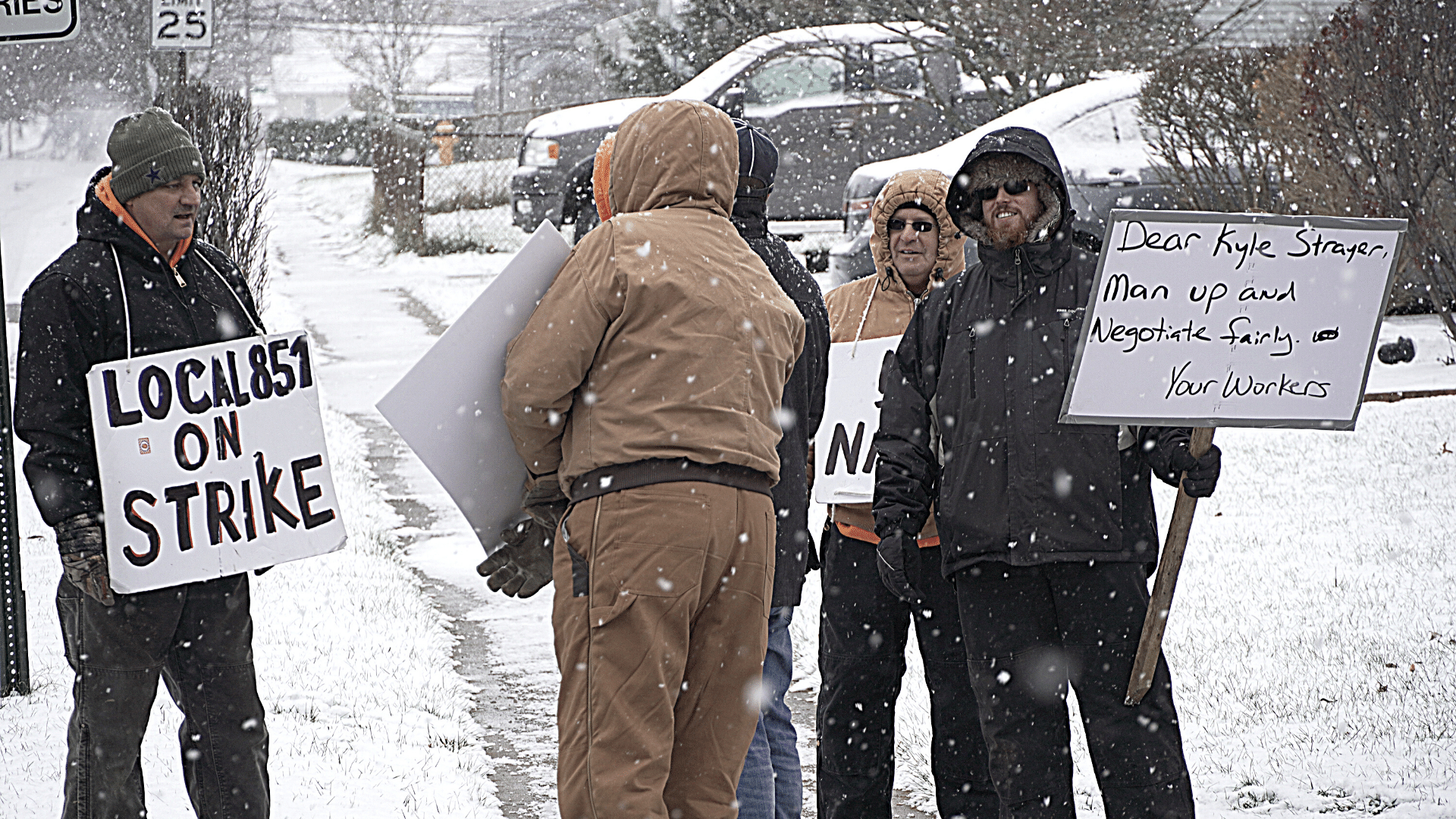

Navigating slick icy patches of mud, they pack into an SUV to go picket at the home of 36-year old Strayer CEO Kyle Strayer.

Twenty-eight ironworkers are still on strike at Strayer and working the picket line in three shifts. But with those 28 at the picket line, the union could only spare four union members to head to Strayer’s house to picket.

Still, the workers are determined to make a statement.

The four workers arrive and take picket signs outside Strayer’s affluent suburban home. Strayer’s neighbors emerge from their home on other sides of cul de sac to watch. The neighbors watch as the burly ironworkers clad in heavy winter coats and jackets, galoshes, and orange ironworkers sweatshirts, march outside Strayer’s home.

“We are escalating things up,” says Tracy Cutright, Ironworkers Local 851 Vice President, holding up a sign outside of Strayer’s home that reads, ‘Kyle, Santa knows, who is naughty and nice.’ ”

Erie Strayer is a family-owned ironworks company that makes prefabricated portable cement mixing facilities used on construction sites. It employs roughly 100 workers in highly skilled work building these hard-to-build mobile construction rigs. Workers are paid on average $19.10 an hour but say they are often pressured to work 50 to 60 hours a week in a region where jobs are scarce.

Kyle’s grandfather, Ham Strayer, was a constant presence on the factory floor in the 1970s and 1980s. Back then, Ham used to host company softball games and was known for having a positive relationship with the union that’s been there for 70 years.

However, the company passed first from Ham Strayer to his son Robert Strayer. Then when Robert died in 2020, the company was passed down to Ham’s grandson, Kyle. The company’s culture changed dramatically.

Gone are the company softball games, the hands-on shop floor presence of ownership, and the sense that the company operated more like a family. Instead, workers say they are subjected to anti-union managers like Vice President Harold Lilly and disciplinary procedures that pressure workers to work seven days a week, with frequent penalties for taking a day off to care for a sick child.

“I actually contracted COVID. And they wouldn’t let me leave,” said 31-year-old George Michael Crawford, who makes $14 an hour at the plant as a master blaster. “I basically provided proof that my son had it and [management] said that I needed to go get a quick COVID test [and] no, you can’t leave till the end of the day and go get a test.”

When Glen Ybanez’s parents died a few years ago back in California, Strayer made him bring in a newspaper obituary of his parents to prove that they were dead. While they asked for verification of his parents’ death (which some companies include in their bereavement leave policies), they also asked for Ybanez’s birth certificate to prove they were actually his parents. Then they made him wake up after 4 a.m. California time every day to call out each day for his pre-approved bereavement leave.

“To me, that’s just wrong. That shows no respect,” says Ybanez as he chokes up, recalling his parents’ deaths.

Workers also say they struggle to get the company to approve a doctor’s note when sick. Unlike other union workplaces where workers are given discretion for a certain number of sick days each year, Strayer workers enjoy no such freedom.

Workers say Strayer has little reason for such strict policies other than maintaining power over workers.

“It’s all a power trip for them,” says local union president Cyril Bauer. “The whole contract is just a power trip for them to have their thumb on top of us.”

Now, workers are fighting back.

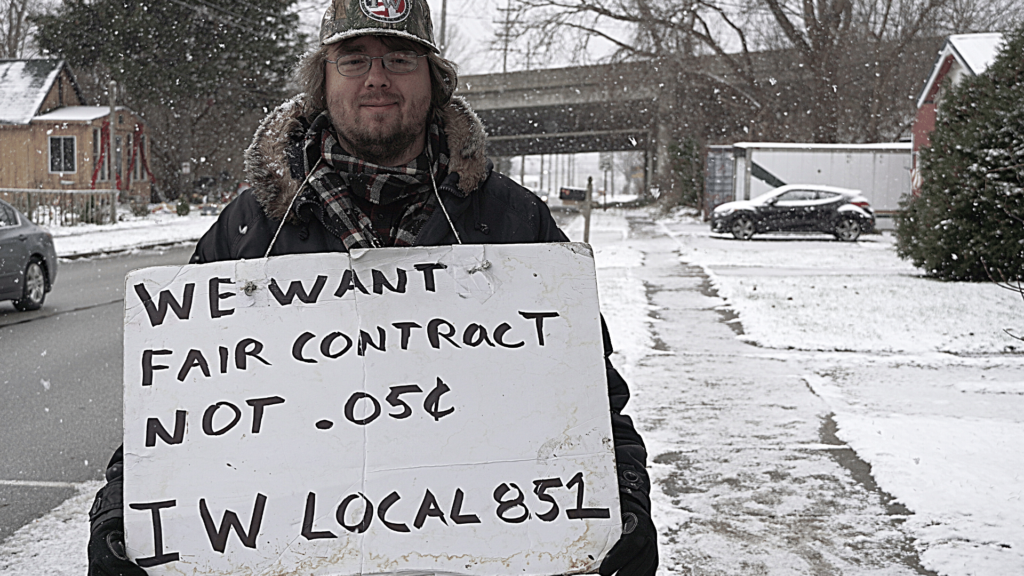

Their union contract expired in March, and for more than six months, the union tried to negotiate, but management hardly budged. They offered to give workers, who on average make $19.10 an hour, a .05 cents an hour raise. Additionally, the workers would have to pay more for healthcare and would have to put up with attendance policies that still penalize them for taking days off to be with their sick children.

“Basically, if we accepted this contract, I would be making less money with inflation in a year or two,” says 32-year-old Steven Carpenter, whose family has worked at Strayer for three generations.

Frustrated with the company’s refusal to budge on their positions, the union went on strike on October 2. Their strike came in the middle of a period of intense strike activity dubbed #Striketober as the media began to cover the growing strike wave more and more.

Quickly, their strike has inspired the Erie labor community, a community with a deep history of trade unionism. Over the two days that we spent on the picket line, we saw scores of community and union members show up with donations of food, coffee, and in some cases, cash.

“Sometimes it’s honestly overwhelming,” Bauer says. “I mean, you get like 20 packs of crackers. How many crackers can a guy eat?”

These donations have helped the workers stay strong as the frigid winter winds from Lake Erie pick up.

“We had one woman stop by and drop off 32 individual $25 gift cards to Giant Eagle [a local supermarket],” says Bauer. “She said she got the money from her church and just wanted to remain anonymous. She just wanted to help.”

The union has raised $13,000 with a GoFundMe Strike Fund to help them continue to hold the line.

With Christmas approaching, local union members have organized toy drives to help buy presents for the kids of strikers. On Saturday, December 18, the PA AFL-CIO has scheduled a special Christmas party for strikers’ children from VFW Local 470 from 10 am to noon.

“The strength in the community has been more than generous,” says Crawford. “The generosity has just been overwhelming. It definitely helped me to realize the power of unions.”

Not only has the community invested heavily in organizing on behalf of strikers, but their international union that’s made of 150,000 members Ironworkers has invested heavily as well. They have sent multiple staffers up from the international union to help them build a special website for them to rally support from union members in Erie and around the country.

Many unions tend to invest heavily in large fights involving several hundred workers. Many unions do a cost-benefit analysis and prefer to invest in their largest shops with lots of dues-paying members and hence political power within internal union structures.

However, the Ironworkers, in addition to representing tens of thousands of ironworkers employed as construction workers around the country, also represent scores of specialized small shops with 50 to 100 workers like Strayer that make equipment and rigs for construction sites.

The strike is currently the only strike in the Ironworkers’ 150,000 member union. The international union sees it as an opportunity to show other employers the union’s degree to fight for only 28 union members.

“Our international was all in on this,” says Ironworkers Local 851 Vice President Tracy Cutright. “They support every ironworker, whether they are in Boston on top of a structure or if he’s right here in a shop at a press. They support every iron worker and so if they feel they get away with it here, they’ll get away with it anywhere.”

Cutright says that the strike has garnered so much support from the Erie labor community and the ironworkers because workers want to see a change in the workplace following the pandemic. Many workers like those Strayer were declared “essential workers” and were forced to risk their lives working through the pandemic.

“I think 2020 pretty much pulled the scab off of labor in America, and people are waking up and realizing things. People are starting to see the problems,” says Cutright. “It’s sort of like being in a toxic relationship with some employers, you know, you don’t realize you have that issue, until you take that step back. And you’re looking at it from the outside and you’re like, Wow, I can’t believe I put up with that for so long.”

The strike is an exciting moment for third-generation Strayer union member Steven Carpenter.

“I’m glad to be on strike, because it means that we’re actually having a chance to be able to fight back for the past 10 to 15 years that I’ve seen the U.S. I’ve been watching unions shrink down,” he says. “And I’m glad that people are finally being able to stand up for themselves and say that this stuff is ridiculous.”

At the beginning of the strike, 41 workers were out on the picket line. Five workers from the union have scabbed and crossed the picket line, while another eight have gotten jobs elsewhere during the strike.

Still, with only 28 strikers, massive community support, an unusually heavy investment from the Ironworkers international union, and a new sense of comradeship emerging on the picket line as workers get close, union members at Strayer say they are determined to hold the line as the harsh winter months set in on the shores of Lake Erie.

“These 28 we aren’t moving basically,” says Carpenter. “We are gonna hold the line.”

Donate to Help Us Cover Strikers as the Holiday Season Approaches