The following research was first presented at the National Baseball Hall of Fame by Emmy-nominated labor reporter Mike Elk as part of the 36th annual Symposium on Baseball and American Culture. It is the result of more than two years of work.

The 1945 GI World Series in Hitler’s Nuremberg Stadium: Baseball’s ‘Double Victory’ Against Segregation at Home and Abroad

By Mike Elk & Phil Moon

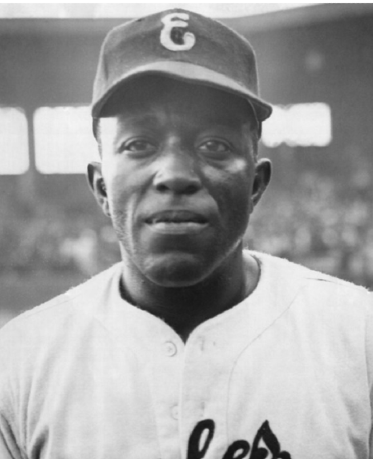

On March 7th 1995, Leon Day was lying in hospice care at St. Agnes hospital in Baltimore when he called his wife to tell her that he had finally been elected to the Hall of Fame for his excellence as a Negro League player.

“I said, ‘Leon you are not in, not yet,’” said his widow Gerladine Day.

She told him that the Veterans Committee of the Hall of Fame wasn’t announcing the results for another several hours.

Slowly, Day, who was heavily medicated, began to realize that he had dreamed his entire induction ceremony.

A few hours later the Baseball Hall of Fame did call Day to tell him that he had been inducted into the Hall of Fame, despite never playing in the Major Leagues.

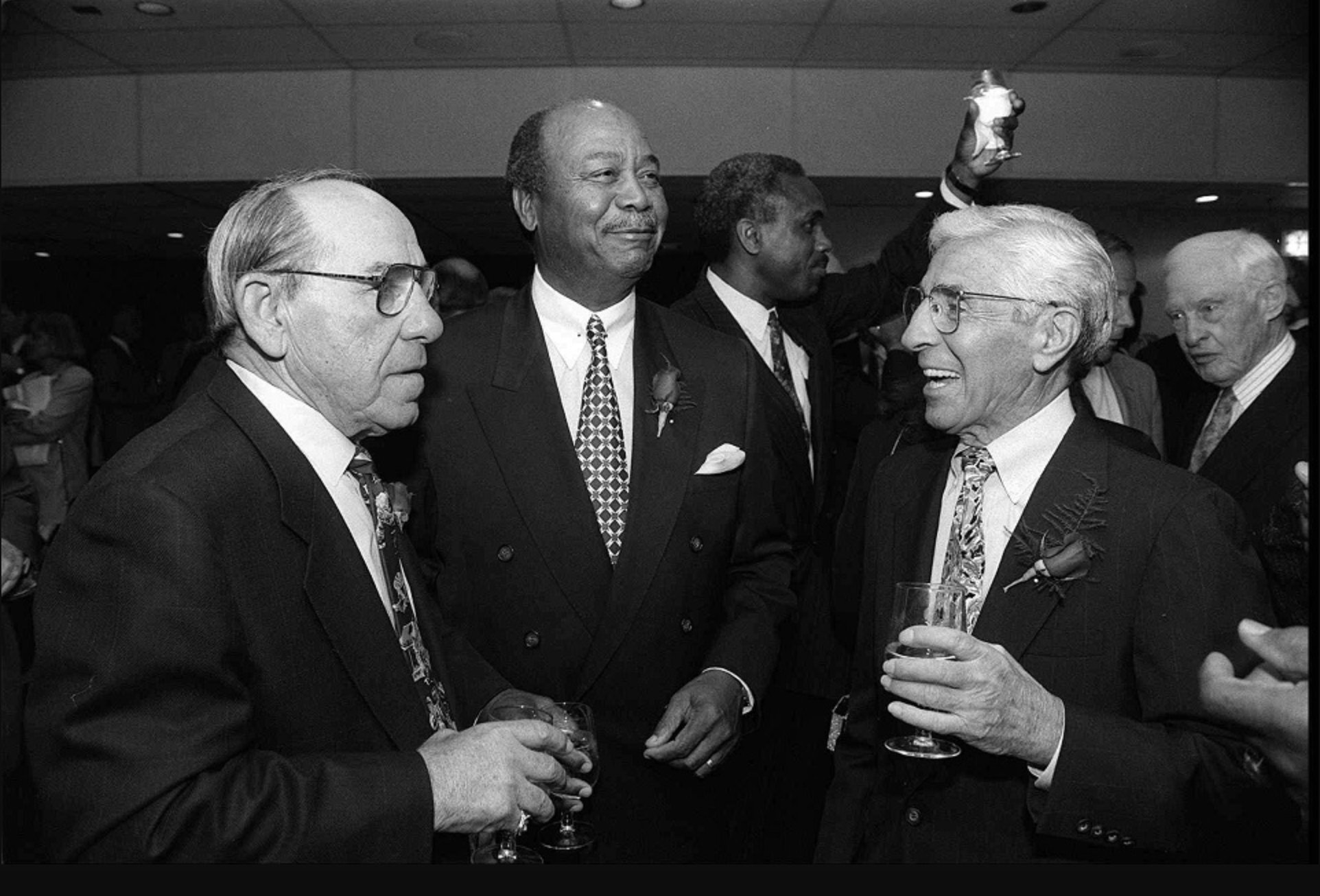

For decades, Monte Irvin had argued that Day deserved a place in the Hall of Fame.

“Leon was as good as Satchel Paige, as good as any pitcher who ever lived, but he never made any noise,” said Monte Irvin, a fellow Normandy and teammate of Day's on the Newark Eagles.

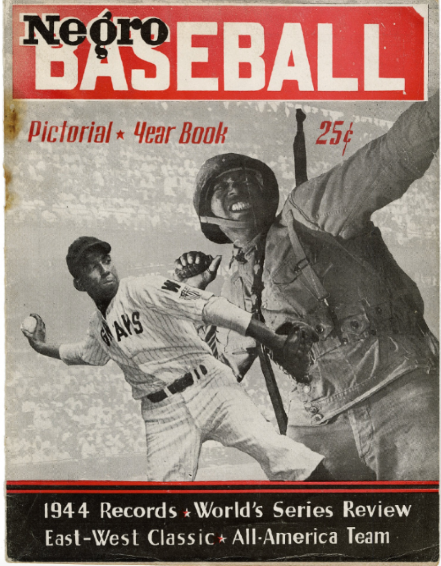

The Pittsburgh Courier, the leading Black newspaper in the country at the time, credited him as being the best Negro League pitcher in 1942 and 1943. After the war, he served as the ace of the Newark Eagles team that won the 1946 Negro League World Series.

However, Day likely lost his chance to play in the Major Leagues when he was in the Army during World War Two, serving in combat in Normandy.

Six days after receiving the news of being inducted into the Hall of Fame, Day died of heart failure.

“I really think that Leon waited for [his election] because Leon had been sick for quite a while,” said his sister, Ida May Bolden.

When asked what his favorite game was, Day replied that it happened in Hitler’s Nuremberg Stadium in Germany in 1945.

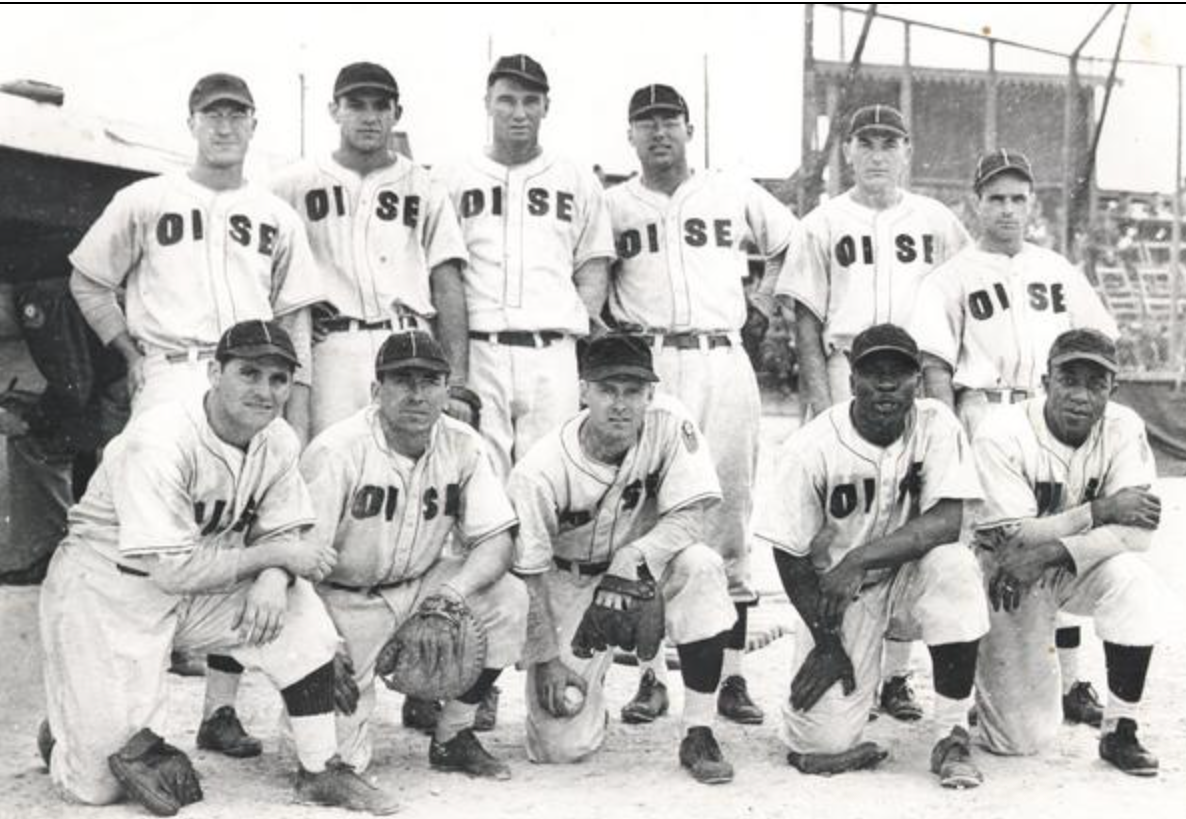

The game was part of the GI World Series, a set of games largely erased from the record books despite its history-setting precedent. Leon Day, alongside fellow Normandy combat veteran and future Hall of Famer Willard Brown, the

mixed race OISE (Overseas Invasion Service Expedition) All-Stars team.

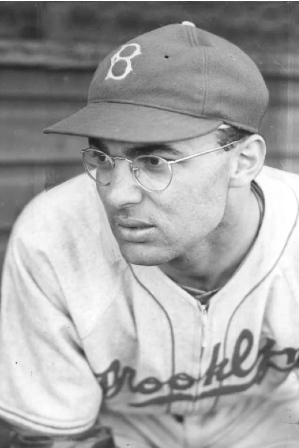

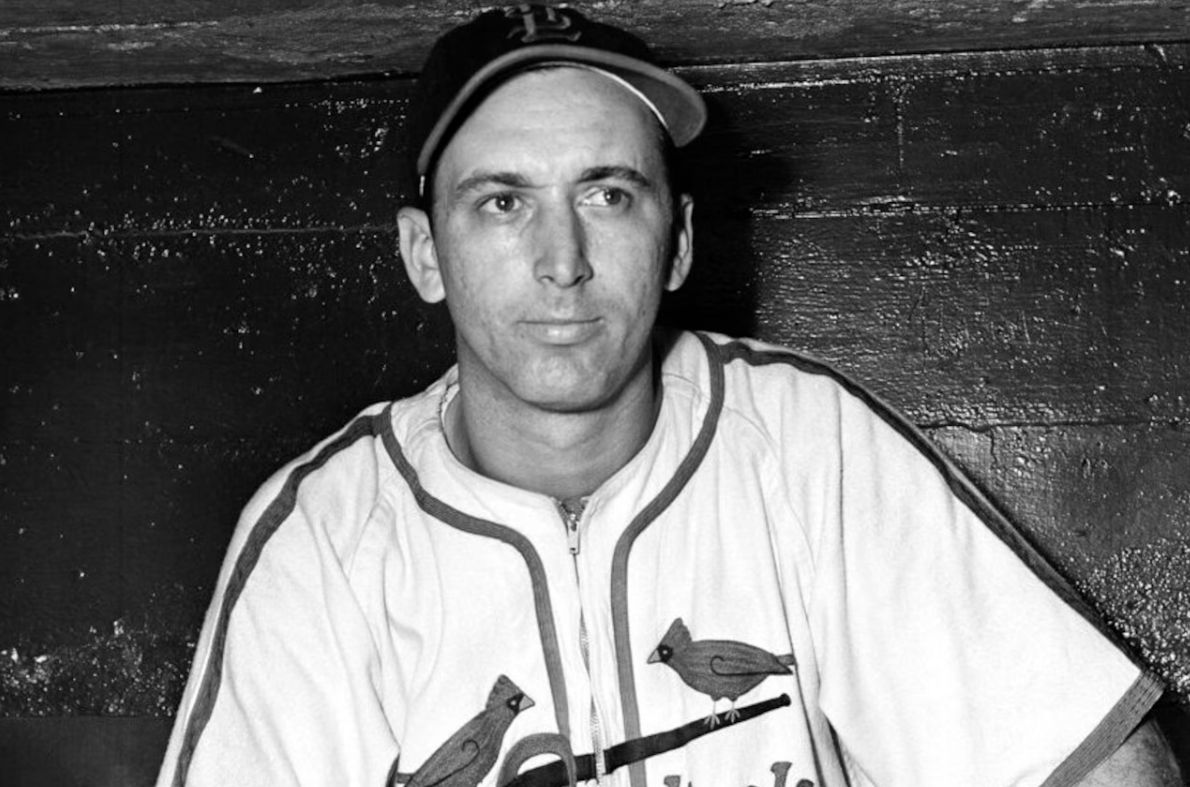

Leading the team was Sam Nahem, a Brooklyn-raised, Jewish card-carrying member of the Communist Party, who was a pitcher for the Dodgers, Phillies, and Cardinals.

In a David vs. Goliath story played out in front of 50,000 GIs, the integrated All-Stars faced the 71st Infantry Division’s Red Circlers led by Harry Walker, the future leader of a strike attempt to keep Jackie Robinson out of Major League Baseball a year later. The team featured three All-Stars: Walker, Ewell Blackwell, and Johnny Wyrostek, more All-Stars than the 1945 World Series-winning Detroit Tigers.

“[The Red Circlers] had more All-Stars than the Detroit Tigers so this was a significant moment in time, and then to do it there in Germany, literally in the face of Hitler, that resonates, that says something powerful,” says Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro League Baseball Museum in Kansas City, “This was so significant because I think it helped people understand that there was no inferiority between these Black and white players.”

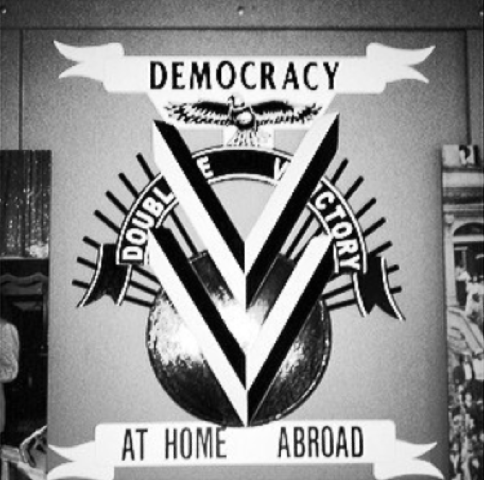

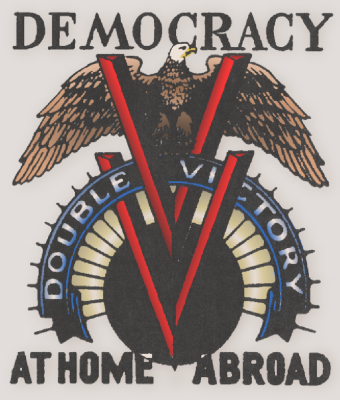

The game was emblematic of the Double V Campaign that had inspired many during World War Two.

The Double V Campaign

Two months after the US declared war on the Axis another declaration was made, not in a speech or law in Congress, but in a letter published in the nation’s biggest Black newspaper, The Pittsburgh Courier.

In February of 1942 James Thompson, a 26 year-old Black cafeteria worker at a defense plant in Wichita, wrote to The Pittsburgh Courier complaining of the racism he faced. Referencing the “V for Victory” popularized by Winston Churchill, Thompson called for African-Americans to start a “Double V” campaign.

“The first ‘V' for victory over our enemies from without, the second ‘V’ for victory overour enemies from within,” wrote Thompson. “For surely those who perpetuatethese ugly prejudices here are seeking to destroy our democratic form of government just as surely as the Axis forces.”

The Double V campaign was more than just a catchy slogan, it was a threat of direct action and work stoppages.

After the threat of marches organized by Black union leader A. Phillip Randolph, Franklin Roosevelt responded by establishing the Fair Employment Practices Committee to end discrimination in the defense industries.

However, many employers continued to practice discrimination by keeping Black workers out of the best, more skilled jobs at defense plants, particularly at major automakers in Detroit. African-Americans inspired by the Double V campaign engaged in frequent illegal wildcat strikes.

The Roosevelt Administration, desperate to ship war goods overseas, responded by pushing employers to do more. The military also opened more positions to Black soldiers, such as pilots, tank crews, and finally allowed Black troops in the Marine Corps.

The federal government even allowed Black and white troops to play high profile baseball games in the military, something which Major League Baseball did not allow at the time. Negro Leagues owner got behind the "Double V" campaign by holding Double V events at ballparks and prominently demonstrating Double V campaign symbols on uniforms and stadium signs.

“I've often said that if you were going to look at one single event that led to the integration of baseball, it would be indeed World War II,” says Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

During World War Two, five Black members of the Hall of Fame would serve in combat or in forward areas overseas: Monte Irvin, Larry Doby, Willard Brown, Leon Day, and Buck O’Neil.

White Hall of Famers Yogi Berra and Bill Veeck, who were both wounded in action, as well as Washington Senators star Mickey Vernon, who played in the South Pacific with Larry Doby, would also play significant roles in the push for the integration of baseball after World War Two.

Not only did these players fight overseas, but they embodied the spirit of the Double V campaign, on the battlefield and ballfield.

The Fight Before the War

Before the war the Black press had been major advocates for integrating baseball.

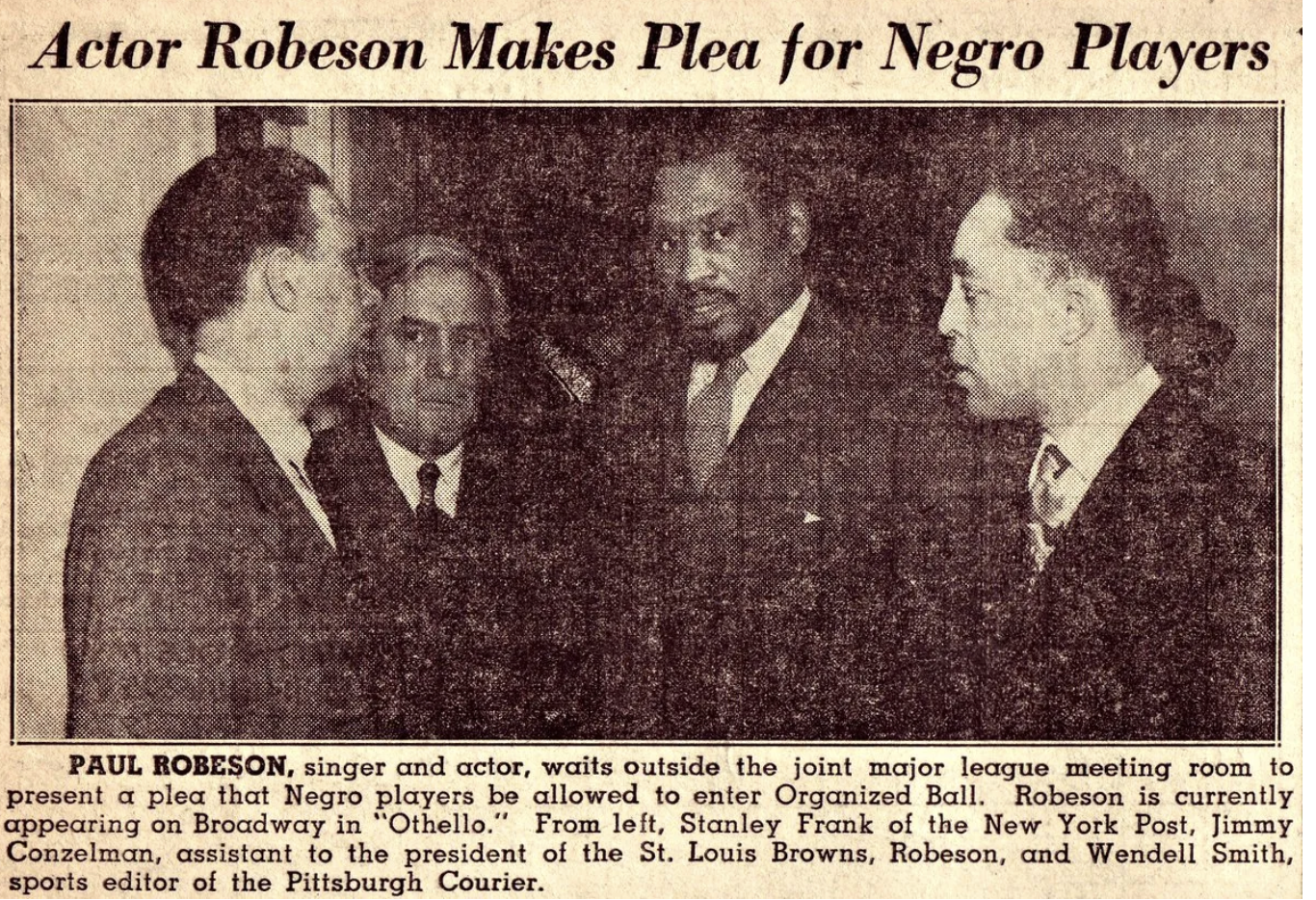

In 1933, The Pittsburgh Courier’s Chester Washington ran a four-month feature with interviews of white players and executives about the color line in baseball. Wendell Smith, who joined the newspaper in 1937, used his sports column to call for integration, and lobbied MLB executives behind the scenes about which Black ball players they should try out.

Sam Lacy of the Washington Tribune and the Baltimore Afro-American was another prominent advocate, suggesting to Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith several players for the Homestead Grays who could help his last place team.

Sam Nahem was one of the few outspoken advocates for integration among active players. As one of only ten Jewish players in major league baseball, Sam Nahem had experienced antisemitism throughout his life, and used his position in the minor and major leagues to stubbornly fight to change his fellow ballplayers' minds on integration

“The majority of my fellow ballplayers, wherever I was, were very much against Black ballplayers, and the reason was economic and very clear,”, Nahem told The Jewish News of Northern California in a 2003 interview, “They knew these guys had the ability to be up there and they knew their jobs were threatened directly and they very, very vehemently did all sorts of things to discourage Black ballplayers.”

He was also the only Communist Party member in Major League baseball.

In the late 1930s, the Communist Party, in conjunction with civil rights groups and some unions, picketed at major ballparks including Yankee Stadium, Ebbets Field, the Polo Grounds, and Wrigley Field to call for integration.

When the film Pride of the Yankees was released during the war in 1942, members of the Communist Party even leafleted movie theaters with pamphlets quoting Lou Gehrig calling for the integration of baseball.

The Communist Party’s newspaper the Daily Worker helped galvanize support for integration after Lester Rodney, another Brooklyn-raised Jew, became the newspaper’s sports editor after critiquing the Daily Worker’s negative attitude toward sports, arguing sports could be a means to reach the working class fans.

Under Lester Rodney’s leadership, the Daily Worker ran regular boxscores and updates on the happenings of the Negro Leagues, helping to dramatically expand the potential audience of whites interested in the Negro Leagues.

“In the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, we talk a lot about Lester Rodney,” says the museum’s president Bob Kendrick. “Here you had a white journalist writing for the American Communist newspaper, the Daily Worker, and I think you can make a case that he was extremely influential and might have been as influential as anyone in pushing the agenda for integrating baseball. He was writing consistently and constantly about the great stars of the Negro Leagues.”

As more media attention was paid to the Negro Leagues, attendance at games went up during World War Two. Baseball fans flocked to see some of the older Black superstars like Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, and James Thomas “Cool Papa” Bell, who stayed home during World War Two.

Negro League Players in Combat

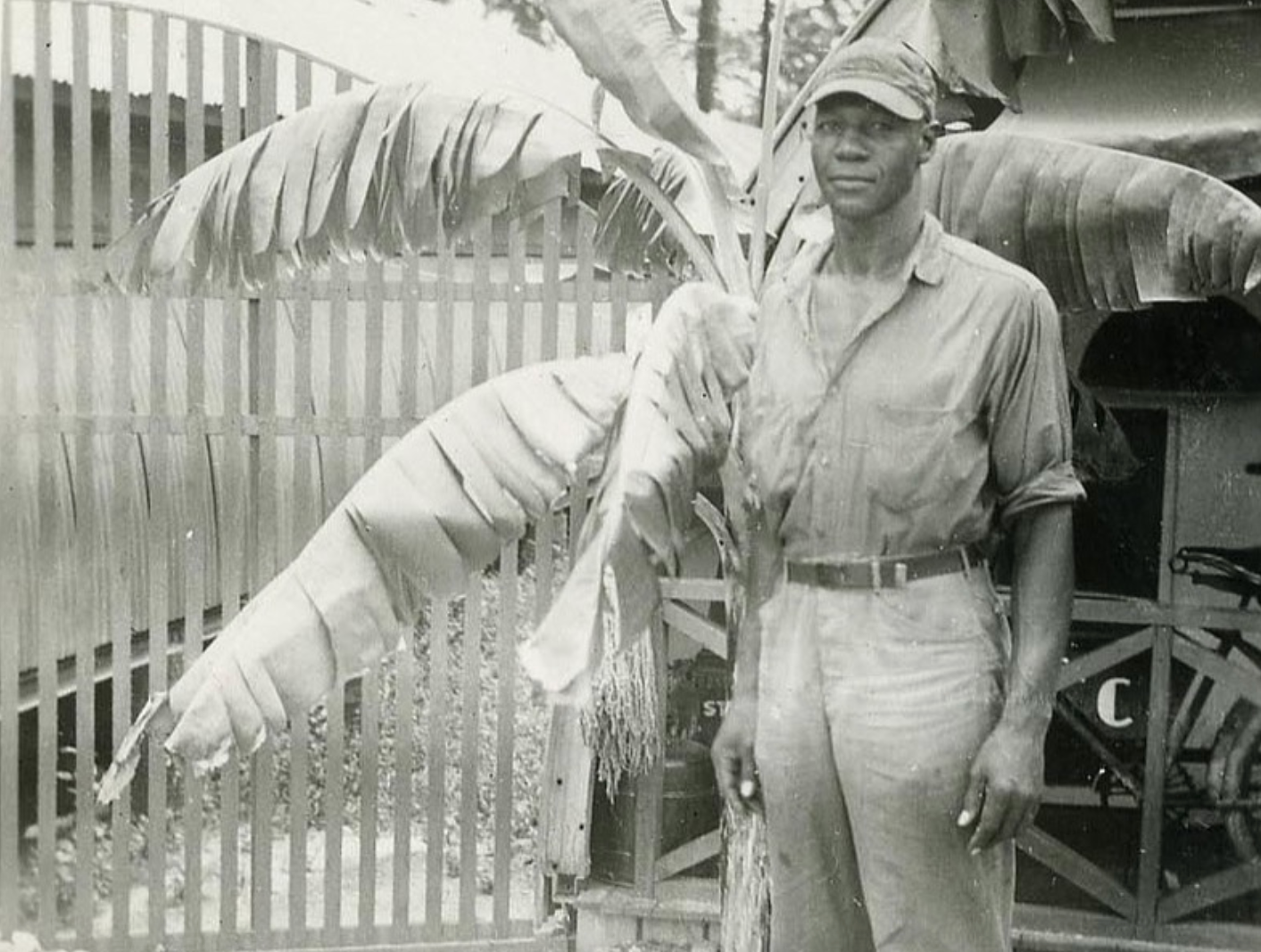

On D-Day, as Yogi Berra manned a machine gun on a boat off of Utah Beach, Willard Brown landed in the third wave with a quartermasters unit under enemy fire.

Six days after D-Day, Leon Day would land on Omaha Beach.

Day was part of the 818th Amphibious Battalion and drove a DUKW amphibious vehicle (known as ducks) that carried supplies from boats to land - a dangerous occupation. The night that he landed, the Luftwaffe strafed and bombed Omaha Beach.

“I’ll never forget June 12. I lost a lot of good friends,” Day told the Baltimore Sun in 1992.

Even as Day faced enemy fire from Germans on Omaha Beach for several weeks, he still faced mistreatment from white soldiers.

“I remember one night when I came out of the water with a load of ammunition and the Germans started dropping flares and lit the beach up so bright that you could have read a newspaper,” Day recounted to author James Riley for his 1987 book Dandy, Day, and the Devil.

“I heard the planes coming. So I jumped out of the duck and ran up the bank,” Day recounted to Riley. “An MP had a hole there, a sandbagged place. I couldn’t see him, but he said, ‘Soldier!’ I said, ‘Yeah?’ He said, ‘Come on in here.’”

“So I went in his hole and I got in there and we were trembling and the planes coming, strafing everything and shooting everything up on the beach. He said, ‘Who’s driving that duck out there?’ I said, ‘I am.’ He said, ‘What has it got on it?’ I said, ‘Ammunition.’

He said, ‘Move that duck out in front of this hole!’ I said, ‘Go out there and move it your own damn self!’”

Day and Brown were among five Black Hall of Famers who served in combat or forward areas during World War Two, as well as Larry Doby, Monte Irvin, and Buck O’Neil.

There was a sense of pride shared by many Blacks and whites about taking on Hitler.

"The most wonderful day happened on June 6th, 1944," said Monte Irvin, who was stationed in England at the time of D-Day, at an American Veterans Center event in 2008. "We saw those P-38s; the sky was full of them. All of us were so happy".

Monte Irvin would land on Omaha Beach on August 1st, 1944 while fighting was still heavy in Normandy.

“I’ll never forget it as you landed on the beach and walked up the beach, there was a long streamer and the streamer said ‘Through these portals, America’s finest soldiers have tread,’” said Irvin, who served overseas with the 1313th Engineers Battalion.

Monte Irvin speaks about the pride that he felt landing on Omaha Beach

While African-Americans served in a handful of combat units, most served in segregated construction and transportation units. Sometimes they served alongside white soldiers, like my grandfather Regis Magill Holden, a Western Pennsylvania bricklayer and union leader, who landed on Omaha Beach just a few weeks before Monte Irvin.

My grandfather was a truck driver in an ad hoc mixed race unit known as the “Red Ball Express.” So, too, were local Homestead Grays catcher Josh Johnson and Newark Eagles pitcher Max “Dr. Cyclops” Manning.

Hall of Famer Buck O’Neil, who served in a Seabees Naval Construction battalion in the Pacific, said that he also experienced racism and discrimination stateside, but when he got overseas he noticed that dynamics changed a bit.

At an American Veterans Center event in 2000, O’Neil recalled an eye opening incident that occured in the Philippines.

One day, O’Neil was on deck of a ship helping to transport ammunition when “Taps” started playing.

“The little ensign on deck said ‘attention niggers,” O’Neil recalled.

“And when he said that I went up that ladder and I said, ‘Do you know what you are saying?’” said O’Neil. “‘I am a Navy man, but I just happen to be Black, see, I’m fighting for the same thing that are you are fighting for.’”

Then, some of the Black Seabees called the captain of the ship and complained.

“The captain blasted him out,” said O’Neil, “Then when [the ensign] really started thinking about it, he really started crying, he was from Alabama, and I said, ‘Don't cry, just don’t do it anymore.’”

Hall of Famer, Buck O'Neil, talks about fighting racism during World War Two

The growing solidarity between soldiers during the War began to be reflected in the official magazines and newspapers of the military. Yank, the official Army weekly magazine with a circulation of 2.5 million GIs serving at home and abroad, ran articles about the issue of race and society.

In 1943, it featured an article on a push by civil rights groups to get the Pittsburgh Pirates to give Leon Day a tryout, which never materialized.

Yank also ran a letter in 1944 by Black Corporal Rupert Trimmingham recounting how German POWs were allowed to eat at southern lunch counters where they were denied the same right. In a sign of the growing support among GIs for civil rights, Trimmingham reported receiving hundreds of letters from white soldiers, who were outraged by the treatment of Black soldiers.

Military Sees More Progress on the Ballfields Than the Battlefields

While the military branches were still largely segregated, limiting the interaction between white and Black soldiers and sailors, on the ballfields they were making more progress than on the civilian home front. While Kenesaw Mountain Landis blocked integration in the Major Leagues as its first commissioner, his powers, however, did not extend to military bases.

The person in charge of those games in North Africa was Zeke Bonura, one of the white All-Stars who played in the first mixed race game at Wrigley Field in 1942. A career .307 hitter for the White Sox, Bonura had a huge fan base among Blacks on Chicago’s South Side.

In 1943, Bonura, based in Algiers, organized over 1,000 baseball players (largely amateur) into 150 teams in 6 leagues.

Bonura would also organize separate leagues for Black players. While Bonura wasn’t yet able to get mixed race teams approved, he did promote a special All-Star game of all Black players in North Africa. Bonura used his celebrity to pose for photos with Black All-Star players in widely distributed military newspapers.

Bonura would later lead efforts to integrate the minor leagues by signing six Black baseball players for the Stamford Bombers as player-manager in 1947, helping turn a team on the brink of folding into the Colonial League champions.

The culmination of the 1943 military season was the North Africa World Series in Algiers.

A play-by-play commentary of the Series was broadcast on the Armed Forces Radio Network and was a smash hit, inspiring the Army to invest heavily in mass organized baseball leagues overseas.

“When the runs, hits and errors of this war are totaled up, and they look around for unsung heroes of the ball game, I’m sure they’ll pin a medal on the broad chest of Zeke Bonura," ” wrote the famous baseballAl Schacht in his 1945 book GI Had Fun, “What he has done for the morale of the American soldier can never be fully revealed except by the GI himself.”

Indeed, General Dwight D. Eisenhower did pin the Legion of Merit on Bonura's chest for his role in organizing baseball games. The military found that baseball games helped soldiers suffering the effects of “combat fatigue” (now known as PTSD).

“You’d be surprised how quickly a man snaps out of it after going through an invasion,” said Seattle Rainier's Vice President Roscoe Torrance, who the Marine Corps tapped to organize baseball games in the Pacific.

In the book Playing for Their Nation, Steven R. Bullock recounts how massive resources were invested in building hundreds of baseball fields all over the world.

In Papua New Guinea, before lighting had become common in major league baseball, Army engineers constructed a baseball field with twelve 800 million candlepower lights. According to the Sporting News, no major field could boast even “one-twelfth of the candlepower.”

Prior to serving in the Navy in the South Pacific during World War Two, Larry Doby, a future Hall of Famer who was the first African-American to play in the American League, did not believe that he would ever get the opportunity.

However, while stationed on Ulithi, a remote naval base in the South Pacific, he played baseball with Washington Senators star Mickey Vernon, a 6-time All-Star and 1946 batting champion, and future All-Star Billy Goodman.

It was the first time that Doby had ever befriended a Major Leaguer and it was the first time that Vernon had been friends with a Negro Leaguer.

MLB Fights Against Baseball Integration At Home

While Zeke Bonura and other military leaders were letting Black baseball players compete in high-profile integrated games, the same couldn’t be said of the MLB back at home.

At the beginning of World War Two, the first mixed race game was held at Wrigley Field on May 24, 1942. Over 29,000 attended the game with proceeds going to the Navy Relief Fund.

Playing for the Monarchs were Satchel Paige, Willard Brown, and Joe Greene, who would later star in the GI World Series of Italy in 1945.

The white All-Star team featured future Hall of Famer Bob Feller; Cecil Travis, a 3-time All-Star, who would later win a Bronze Star in the Battle of the Bulge; and John Grodzicki, a Cardinals pitcher, who would be wounded while fighting with the 17th Airborne in Germany.

It was an exciting ballgame with Satchel Paige limiting the Dizzy Dean All-Stars to only one run and the Monarchs winning by 3-to-1.

A week later, Pittsburgh Courier journalist Chester Washington wrote a widely published open letter to MLB Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis calling on him to integrate baseball.

Washington cited the example of African-American hero Dorrie Miller who was awarded the Navy Cross for shooting down two Japanese airplanes in the attack on Pearl Harbor, despite lacking any training on the anti-aircraft gun that he was firing.

“Dorrie Miller got his big chance to man a Navy gun and won the Navy Cross. His heroism at Pearl Harbor was not in vain,” wrote Washington. “And, if Jolting Josh Gibson, the batting Big Bertha of Negro baseball, were only given an opportunity, he could be one of the big guns of major league baseball.”

He closed the letter by writing “P.S. Did you read about the Kansas City Monarchs drawing 30,000 in Chicago last Sunday against Dizzy Dean's major-league All-Stars and beating them 3-1?”

Five days later, Landis, a strict segregationist, would outlaw Major League club owners from renting their ballparks for mixed race baseball games.

FBI Spied on MLB Integration

In December 1943, Pittsburgh Courier sportswriter Wendell Smith arranged a meeting of seven publishers of Black newspapers to discuss the race issue in baseball. Paul Robeson, a member of the Communist Party, was also in attendance.

Later, it was discovered that the FBI spied on the meeting. J. Edgar Hoover even recommended indicting the attendees. With Black workers engaged in wildcat strikes at major employers, civil rights groups could have been brought up on legal charges of violating the anti-strike wartime productions laws.

At one point in 1944, Attorney General Frank Biddle summoned John Sengstacke, the owner of the largest chain of Black newspapers in the country, and Charles Browning of the Chicago Defender to a meeting in Washington and threatened to bring them up on sedition charges.

However, after a tense meeting, the Attorney General backed down in exchange for the newspaper owners agreeing to cool off their rhetoric.

Victory in Europe and the GI World Series

With the war coming to end in the summer of 1945, the military found itself with a big problem - more than three million troops were stationed in Europe, with very little to do, and a long wait to either head home or see combat again in the Pacific.

To keep the troops occupied, the Army organized an extensive network of baseball leagues and playoffs.

In Northern Europe, Italy, and the Pacific, the military organized GI World Series in each theater featuring both Major League and Negro League stars playing baseball together.

In Italy, the all-Black 92nd Infantry Division’s baseball team featuring a number of Negro Leaguers beat a series of all-white teams to win the GI World Series of the Mediterranean Theater.

The team featured Satchel Paige's catcher Joe Greene from the Kansas City Monarchs. He had been wounded in combat while serving with an anti-tank unit. When Benito Mussolini and his mistress were killed and hanged upside down outside of a gas station in Milan, Greene and his unit were given the task of cutting down the rotting bodies and burying them

In the South Pacific on the islands of New Caledonia, there was a similar GI World Series featuring Buster Clarkson, a Negro League star, who would make his major league debut at age 37 in 1952 for the Boston Braves.

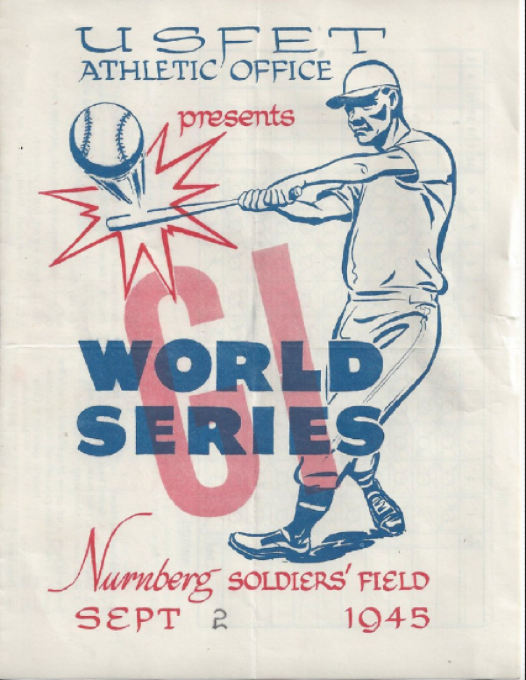

The “Double V” GI World Series in Hitler's Stadium Nuremberg

The GI World Series for the European Theater of Operations has largely been erased from histories of the war, but the game embodied the spirit of the “Double V” call for victory against facism abroad and racism at home. The five-game series was split between two games in Reims, France, where the Nazis had signed their surrender, and three games, including the decisive Game Five, in Nuremberg.

From 1932 to 1938, the Nazi Party held its annual conferences at Nuremberg Stadium. The 1934 Nazi Party rally attended by more than 700,000 Nazis was made famous around the world by Leni Riefenstahl’s landmark film Triumph of the Will.

The stunning images of hundreds of thousands of Nazi Party members marching in front of Hitler in Nuremberg were shown around Germany. Hitler praised the film forrecruiting millions to Nazism and being an "incomparable glorification of the power and beauty of our Movement."

Unfortunately, the GI World Series was not filmed, but it should have been.

The 1945 GI World Series featured more All-Stars than the ‘45 World Series, which baseball historian Warren Brown labeled the “World’s Worst Series.” Baseball writer Frank Graham joked that the quality of play was comparable to “the fatmen versus the tall men at the office picnic.”

The 71st Infantry Division’s Red Circlers team was backed by General George Patton, the legendary commander of the Third Army. A ruthless competitor with other generals, Patton was determined to win the GI World Series.

Patton pulled strings to have professional players transferred to his command, even lending their team’s captain, Harry “the Hat” Walker, a B-17 so that he could travel around and collect the best Major League ballplayers in Germany at war's end.

Walker was a 1943 All-Star and had been a key part of the St. Louis Cardinals team that won the 1942 World Series. He had seen brutal combat in the closing days of World War Two as a scout for the 65th Infantry Division, winning the Bronze Star, and played baseball with a piece of shrapnel still stuck in his back.

A native of Alabama, Walker was a notorious bigot, who would later lead a failed effort to call a strike by white ballplayers to keep Jackie Robinson from integrating the Major League.

Hall of Fame second baseman Joe Morgan would write that “Harry Walker was the most blatant racist that I ever met in baseball.”

Walker stocked the Red Circlers with “good old boys.” Their ace was Ewell Blackwell, a 6-time All-Star, whose deceptive windup led future Hall of Fame Roy Campanella to label him the best right-handed pitcher he ever faced. After the war, Blackwell would face Jackie Robinson and berate him “with an explosion of racist insults” before Robinson hit a single off a pitch.

Their pitching staff included Phillies ace pitcher Ken Heintzelman, who would become known as one of the “Whiz Kids” that helped the 1950s Philadelphia Phillies win the NL pennant.

Their rotation also included Walker’s Cardinals teammate, pitcher Al Brazle, who would play a key role in helping win the World Series in 1946, and New York Giants veteran pitcher Ken Trinkle, who had a career ERA of 3.74 and was awarded a Bronze Star during the Battle of the Bulge.

All-Star Pirates outfielder Johnny Wyrostek helped to shore up the middle of the order alongside Harry Walker. The team’s starting lineup was almost entirely major leaguers including Pittsburgh Pirates left fielder Maurice Van Robays, Reds second baseman Benny Zientara, Dodgers utility infielder Bob Ramaztozzi, and Cardinals catcher Herb Bremer.

Prior to World War Two, both Sam Nahem and Walker were teammates on the 1941 Cardinals. They could not have been more different - Walker was a racist from Alabama while Nahem was a Jewish communist from New York.

Just as different as the two men were their roster selections. Nahem picked a lineup for the OISE All-Stars that mainly consisted of minor leaguers and even some college players. Other than himself, there was only one other MLB player - Russ Bauers, who was a top pitcher for the Pittsburgh Pirates in the late 1930s before being injured. But the roster included two unorthodox choices for the segregated Army – Negro League stars Willard Brown and Leon Day.

Willard Brown was an 8-time Negro League batting champion and a career .351 hitter. Brown would be the first African American to hit a home run in the American League - an inside-the-park home run in Detroit in August of 1944.

Leon Day was named the best Negro League pitcher by The Pittsburgh Courier in 1942, setting a Negro League record for striking out 18 batters in a game in 1942 and outpitching Satchel Paige in the 1942 World Series. He also held a career .313 hitter in the big leagues.

This underdog team of two marginal MLB pitchers, two Negro League stars, and a collection of minor league and college players would go up against a Major League roster led by bigots and backed by one of the most powerful generals, on the grounds where Nazism rallied before the commands of Hitler.

50,000 Pack Nuremberg Stadium for the GI World Series

Game One of the series was on September 2nd. Earlier in the day, Japan had formally surrendered and many troops were celebrating not having to return to combat. Beer was flowing and troops from all over rode trucks or hitchhiked in as 50,000 packed Nuremberg Stadium to watch the all white 71st infantry Division Red Circlers and the OISE All-Stars.

The game, though, was pretty disappointing for them.

Despite still recovering from strep throat, Ewell Blackwell, pitching for the Red Circlers, struck nine players out. The OISE All-Stars committed a ghastly 7 errors and were routed 9-2.

It looked like the Red Circlers might easily sweep the OISE All-Stars in the five game Series.

Then, Leon Day took the mound in Game Two. Day used a rapid-fire, no-wind up approach that baffled hitters.

“He threw that ball more or less from his hip. He didn’t rear back and come right over his shoulder," said Philadelphia Stars Gene Benson. "He came right from his thigh, but he would whistle the ball and make it move. He could bring it!

Harry Walker, who would win the 1947 batting championship, complained that he had never seen Day pitch prior and struggled to read his unusual pitching windup.

“I knew who Walker was,” Leon Day would recall years later, “But I never had any trouble with him or any of the other major leaguers.”

The game remained scoreless until the 5th when Willard Brown hit a single to the outfield to score minor leaguer Joe Herman. In the next inning, Sam Nahem knocked in Emmet Altenburg to score another run.

In the 8th, the Red Circlers battled back. Harry Walker doubled to score Reds second baseman Benny Zientara.

Next, Pirates outfielder Johnny Wyrostek came up to plate with the tying run on second. Day struck out the future All-Star to close the inning and win the game by a score of 2-1.

Day would pitch a complete game masterpiece that day, striking out ten while allowing only four hits and only one run; winning the game

Three days later, the teams played two games in Reims.

Game Three was a pitchers’ duel between Sam Nahem for the OISE All-Stars and Ewell Blackwell for the Red Circlers.

The game was scoreless until the 4th inning when a grounder by Willard Brown was misplayed by the Red Circlers’ Russ Kerns. University of Minnesota baseball standout Tony Jaros then singled to the left to move the runners over. Both would score when minorleaguer Nick Macone smoked a double to deep left-center field.

In the 6th inning, Johnny Wyrostek hit another run for the Red Circlers. It looked like Nahem might be tiring, but then he struck out future New York Giants outfielder Garland Lawing to end the inning

Despite Blackwell throwing nine strikeouts and allowing only one walk, it wasn’t enough as the OISE All-Star won again by only one run to take the series lead 2 games to 1.

However, Game Four was a complete rout of the OISE All-Stars. Harry Walker hit a home run off of Leon Day in the fourth, and Johnny Wyrostek would hit a double to spark a two-run rally by the Red Circlers.

With Day struggling, Nahem pulled him out of the game and inserted former top Pirates pitcher Russ Bauers. Bauers gave up another run.

Once again the OISE All-Stars squad of mainly minor leaguers struggled to hit against the big league talent of the Red Circlers. They were shut out 5-0.

The Decisive Game Five in Nuremberg

With the series tied 2-2, the GI World Series went back to Nuremberg Stadium on September 8th for the deciding Game Five.

The energy in Nuremberg was electric. Stars and Stripes wrote that “[T]he game was so close all the way through that it kept the crowd of over fifty thousand on its feet cheering wildly and rewarding unfavorable decisions with sounds as wild as any ever to emerge from Ebbets Field or the Polo Grounds.”

Sam Nahem started for the OISE All-Stars and pitched well before giving up a run in the 4th inning. Then Nahem loaded the bases.

Sensing that he had lost his cool, Nahem made a bold call and took himself out of the game. He then called in Bauers to pitch for him. Bauers got the team out of the jam.

Pitching for the Red Circlers, Ewell Blackwell kept a shutout game going until the 7th when Leon Day got his opportunity for revenge.

After a teammate singled in the 7th, Day was sent in to pinch run for him. Day then promptly stole second. He followed that by stealing third.

The next batter hit a deep fly ball to right field and Day ran back to third base to tag up and then hustled out to home plate, scoring a run and tying the game 1-1.

In the 8th inning with a man on first, Willard Brown went to plate and hit a bomb that hit the fence, narrowly missing becoming a home run. The lineup would strand Brown and the game remained tied 1-1.

In the top of the 9th, Nick Macone singled. Then, Frank Smayda bunted to Ewell Blackwell. It should have been an easy double play, but Blackwell made a bad throw allowing both runners to advance.

On the next pitch, Smayda and Macone attempted a double steal. Future New York Giants catcher James Gladd threw wildly. Sensing an opportunity, Macone tried to score, but was thrown out at home, keeping the score tied 1-1.

Then, Lewis “Shine” Richardson, who had played 5 seasons of minor league baseball for the Youngstown Athletics, went up to the plate. The career minor leaguer hit a deep fly to the center field of Nuremberg Stadium to score Frank Smayda and give the OISE All-Star a 2-to-1 lead in the ninth.

With the OISE leading 2-to-1, Johnny Wyrostek came to the plate in the bottom of the ninth and hit a double to deep center. Every hair was on edge as the All-Star Harry “the Hat” Walker then came up to bat with the potential to tie the game with a hit to the outfield. However, Walker flied out to center field, ending the ballgame.

The OISE All-Stars rushed the mound celebrating. A mixed race team of Black, Jewish, and minor league players had beaten an All-Star-packed team in Hitler’s stadium.

When the team returned to France, where the OISE All-Stars were stationed, Brigadier General Charles Thrasher organized a ticker tape parade to celebrate their victory.

The general then organized a celebratory dinner complete with steak and champagne.

“In much of the United States, Willard Brown and Leon Day couldn't have attended a dinner with their white counterparts, many of them who were southern boys,” says baseball historian Peter Dreir, who has extensively studied the game. “But this general said, ‘We're going to celebrate’”.

The historic game was heavily covered by Stars & Stripes and many Black newspapers, but the GI World Series was largely ignored in the American press.

“They were Black and Jewish, the mainstream media didn’t want to hear that because I don't think the public wanted to hear it,” says Bob Kendrick.

The victory came one month before Jackie Robinson would sign with the Dodgers.

A Month Later, Jackie Robinson Signs with the Dodgers

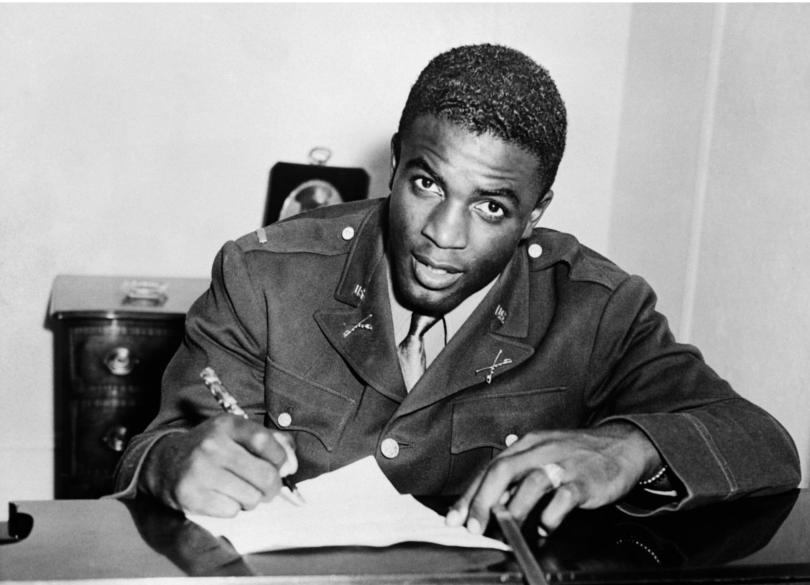

“You can’t tell Jackie’s story without his military story,” says Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro League Baseball Museum.

While stationed at Fort Riley in Kansas, Robinson befriended Joe Louis, who was stationed there. Louis used his celebrity to get Robinson admitted to the Officer Candidate School.

Jackie Robinson would have served in combat with the 761st Tank Battalion, the first Black tank unit. However, he was court-martialed for refusing to sit at the back of a bus at Ft. Hood, despite Army rules desegregating buses on military bases. While he won his court martial case, it kept him out of combat.

When asked by reporters why he decided to allow the integration of baseball, MLB Commissioner Happy Chandler said, “If they can fight and die on Okinawa, Guadalcanal, (and) in the South Pacific, they can play ball in America.”

Over more than one million African-Americans would serve in World War Two and many World War Two veterans would become leaders in the civil rights movement.

When Jackie Robinson was signed, Larry Doby was still stationed at the naval base of Ulithi in the South Pacific.

“I was very happy. I was in the Western Carolinas, on this little island called Ulthi and it came over the news I thought that I had an opportunity,” said Doby in a 1979 interview with the University of Kentucky. “Then the next day, of course, I talked to Mickey Vernon and he said the same thing.”

Vernon would write Washington Senators owner Phil Griffin and encourage him to sign Larry Doby to the big leagues. When Doby started the 1946 season with the Newark Eagles, Vernon sent him a case of bats and told him that next year he would use them in the bigs.

The boost of confidence and support from Vernon meant a lot to Doby, especially considering that Vernon would go on to win the 1946 batting championship.

In 1947, Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck, who had lost a foot as a Marine artilleryman in the Pacific, signed Doby. Veeck had long advocated for integrating baseball, but the Double V Campaign opened the door.

When the Indians first played the Yankees, their catcher, Yogi Berra, a combat veteran of Normandy, went up to Doby to shake his hand and thanked him for his service in the Navy.

The two lived near each other in New Jersey and their kids would play together. They would form a lifelong friendship.

"Other than (Indians second baseman) Joe Gordon, who befriended me right away, I felt very alone," Doby said. "Nobody really talked to me. The guy who probably talked to me most back then was Yogi, every time I'd go to bat against the Yankees. I thought that was real nice, but after a while I got tired of him asking me how my family was when I was trying to concentrate up there.”

Leon Day would never get the opportunity to play in the big leagues. His widow says that Day thought the war had taken its toll on him.

“Leon said, ‘By me being in the army for two and half years and laying down on that wet ground and everything [to sleep], I really had lost my arm,’” his widow Geraldine told WBFF in 2021.

In 1946, Day would throw a no hitter to open the season for the Newark Eagles. Alongside fellow World War Two veterans Larry Doby, Monte Irvin, and Max Manning, he would help lead the team to the 1946 Negro League World Series.

In 1947, Day moved to Mexico City and spent two years playing baseball there for more money than he could have made in the States. He would return to the United States in 1949 to help his hometown Baltimore Elite Giants win a Negro World Series.

He would spend the rest of his career playing minor league baseball, making it as high as Triple A for the Toronto Maple Leafs, but never made it to the bigs.

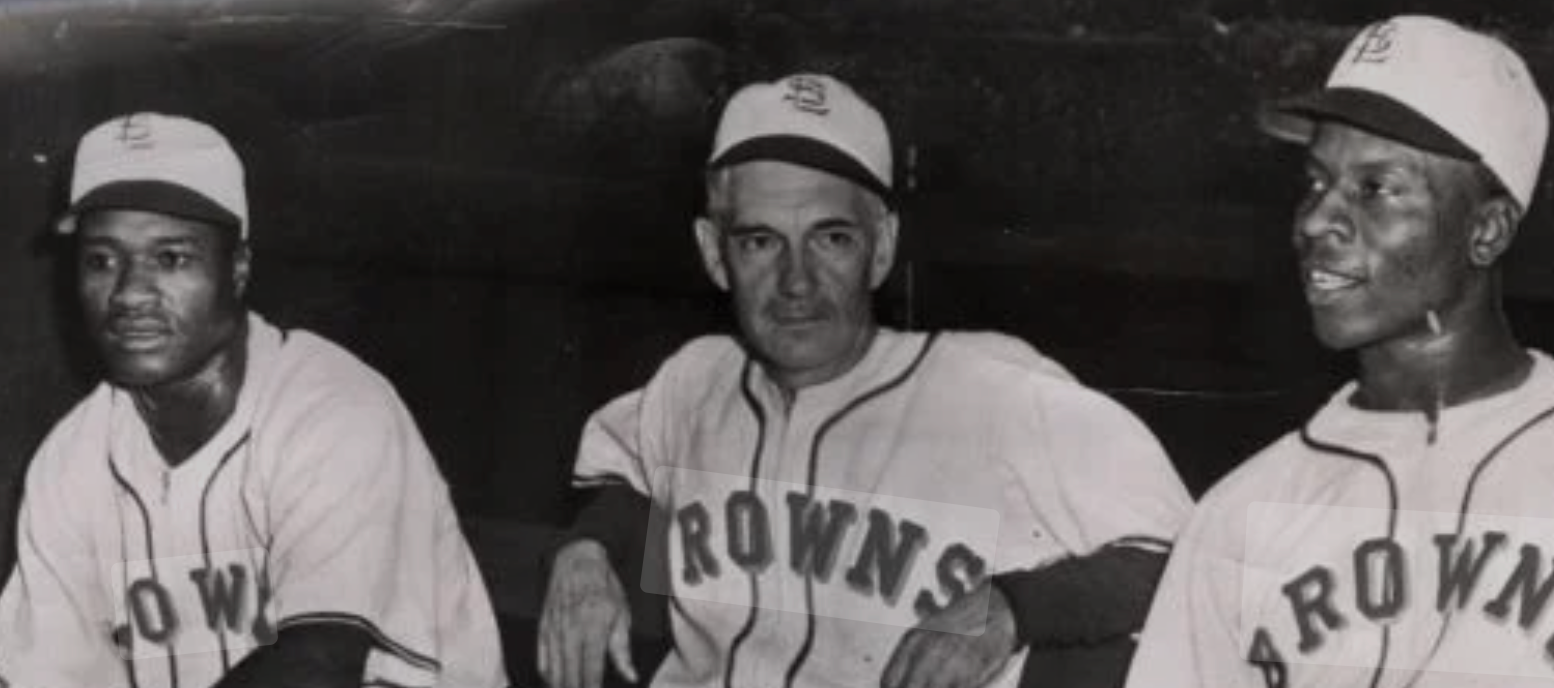

Willard Brown did get a chance to play major league baseball, albeit for a brief period.

In 1947, Brown, who had rushed ashore in the third wave on Utah Beach, and Hank Thompson, a decorated machine gunner who fought in the Battle of the Bulge, were signed by the St Louis Browns as their first Black baseball players.

On August 13, 1947, Brown would become the first African-American to hit a home run in the American League on a hot day at Tiger Stadium.

With the Browns down 5-3 in the 8th inning, the Tigers brought in ace left-handedreliever Hal Newhouser. St. Louis Browns manager Muddy Ruel, not wanting a lefty-on-lefty matchup, tapped Brown to pinch hit.

On the first pitch that Brown saw, he hit a deep drive into center field that hit offof the 426 foot sign in center field.

“I just ducked my head and started running,” Brown told reporters, “and when I came around second and Coach [Earle] Combs waved me to keep on going past third, my legs seemed to sprout wings.”

Brown had become the first African-American to hit a home run in the American League, tying the game 5-5. It was the only home run that Brown would ever hit.

Two weeks later on August 23rd, the Browns would release Willard Brown after he hit only .173 in 21 games.

In 1947, he would re-sign with the Kansas City Monarchs. He would win the Triple Crown in the Puerto Rican Winter League in 1948. He never did play in the major leagues again, but while playing in Puerto Rico he helped mentor two younger players - Roberto Clemente and Willie Mays.

After much lobbying by Buck O’Neil and others, Willard Brown would be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

The Victors Don’t Always Write History

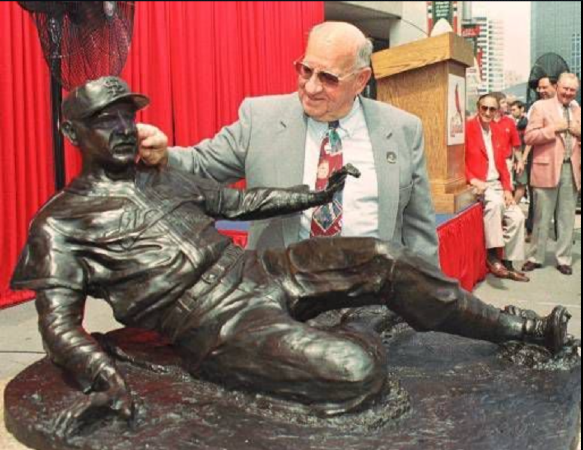

In 1946, Harry “the Hat” Walker would play a key role winning the World Series for the St. Louis Cardinals over the Red Sox.

With the game tied 1-1 in the 8th inning and two outs, Walker would come to the plate with future Hall of Famer Enos Slaughter on first. Walker hit a ball to deep left center field.

Slaughter hustled all the way to third where he ran through the third base coach’s call to stop. Stunned, Boston Red Sox shortstop Johnny Pesky delayed his throw to home and Slaughter scored, landing the winning run for the Cardinals.

The play would become known as “Slaughter’s Mad Dash.” It’s even memorialized in a statue that stands at Busch Stadium in St. Louis.

The statue is considered a shrine for Cardinals fans despite the fact that Enos Slaughter, a southern segregationist, was a notorious bigot. In 1947, he intentionally spiked Jackie Robinson in his leg, with Robinson narrowly avoiding a career-threatening injury.

Althought in recent years, some baseball fans have even begun calling for taking down the statues of Enos Slaugther and Roger Hornsby, who was a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

No statues, though, stand outside of Nuremberg Stadium in Germany commemorating the victory of the mixed race OISE All-Stars over Walker’s Red Circlers. The triumph of a mixed race team captained by a Jewish communist has been largely forgotten to history.

“American historians didn't want you to know,” says Bob Kendrick. “They did us all a tremendous disservice because they kept this chapter of baseball and Americana away from us.”

A statue of Leon Day, though, does stand in the 10,000 square foot Negro Leagues Baseball Museum founded by World War Two veteran Buck O’Neil in Kansas City.

Kendrick says that the Museum is now hoping to expand to 30,000 square feet and build a new section to honor Negro Leaguers who served during World War Two.

In March 2025, as the Trump Administration sought to rid itself of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion initiatives, they removed a webpage from the Department of Defense website about Jackie Robinson. After public outcry, the webpage about Jackie Robinson was reinstated, but NPR reported that more 26,000 images were flagged for removal as a result of the Trump administrations’ anti-DEI initiative.

“I think these aspects of history are on the verge of being lost,” says Kendrick. “And if the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum doesn’t save it, who will?

Donate to Help Us Cover History that Is Being Erased

Acknowledgements.

We would like to thank Michelle Freeman of the Leon Day Foundation, Bob Kendrick of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, "Baseball Rebels" author Peter Dreir, Gary Bedingfield of the site Baseball in Wartime, James Riley, author of Dandy, Day and the Devil, Chevron and Diamonds, and John Miller, author of The Last Manager, for their incredible work as baaseball historians, whose work influenced this project.

Bibliography

American Girls, Beer, and Glenn Miller: GI Morale in World War II (James J. Cooke) - 2016

Baseball at War: World War II and the Fall of the Color Line (Thomas Gilbert) - 1997

Baseball Has Done It (Jackie Robinson) - 1964

Baseball Rebels (Peter Dreier & Robert Elias) - 2022

Bill Veeck: Baseball's Greatest Maverick (Paul Dickson) - 2012

The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (James A. Riley) - 1994

Black Writers/Black Baseball (Jim Reisler) - 2007

Dandy, Day, and the Devil (James A. Riley) - 1987

Fighting for Fairness: The life story of Hall of Fame sportswriter Sam Lacy (Sam Lacy & Moses J. Newson) - 1998

Nice Guys Finish First: The Autobiography of Monte Irvin (Monte Irvin) - 1996

Out of Left Field: Jews and Black Baseball (Rebecca T. Alpert) -2012

Playing for Their Nation: Baseball and the American Military during World War Two (Steve R. Bullock) - 2004

Pride Against Prejudice: The Biography of Larry Doby (Joseph Thomas Moore) - 1988

Press Box Red (Irwin Silber) -2003

Satch, Dizzy & Rapid Robert: The Wild Saga of Interracial Baseball Before Jackie Robinson (Timothy M. Gay) - 2010

Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance (Mark Whitaker) - 2019

The Wendell Smith Reader: Selected Writings on Sports, Civil Rights and Black History (Wendell Smith) - 2023

Veeck as in Wreck (Bill Veeck and Ed Linn) - 1962

Archives

Newspapers and Periodicals

Stars and Stripes

Yank

The Pittsburgh Courier

Sporting News

Baltimore Sun