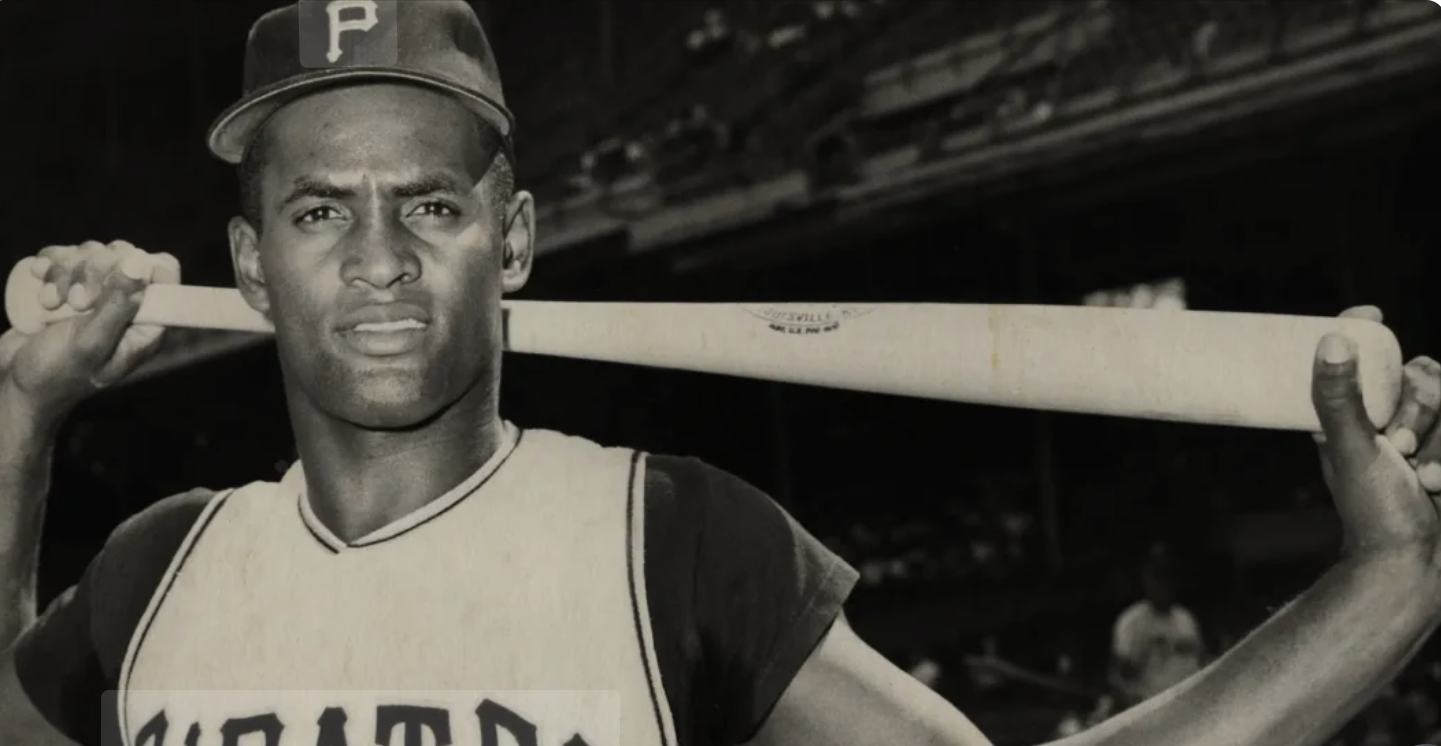

PITTSBURGH, PA - Today marks Clemente Day in Pittsburgh, where the Pittsburgh Pirates, along with the Clemente family, hold several events for Roberto Clemente. With the release of the documentary Clemente this week, new attention has been drawn to the life of Latin America’s first baseball superstar.

However, the film, which heavily features his son Roberto Clemente Jr., who endorsed Trump in 2024, omits both Clemente’s union leadership and his relationship to Martin Luther King Jr. Instead, the film attempts to paint Clemente as a Catholic saint and completely omits his political activism as the National League’s first union representative.

Clemente, 38, died on New Year’s Eve in 1972 while on a humanitarian and political mission to Nicaragua to ensure that post-earthquake aid wasn’t being stolen by the U.S.-backed Somoza dictatorship.

Growing up playing baseball in Pittsburgh, it was drilled into my head by Little League coaches, baseball TV announcers, and teachers that Clemente was a selfless humanitarian who gave his life at the peak of his baseball stardom to help others.

Clemente is, in many ways, the patron saint of Pittsburgh. You can see his face painted on murals and his photo in every sports bar. At the Clemente Museum and other places, there is a lot of talk about Clemente’s Catholicism, but very little talk about his politics.

As the head union representative of the National League, Clemente used his position to call the first player’s strike to honor Dr. Martin Luther KIng Jr., who had been killed the week prior in 1968.

Clemente often said that his political awakening came in 1962 when Martin Luther King Jr. spoke in San German, Puerto Rico. Afterwards, Clemente would host King on his farm and the two would stay in touch for years.

Speaking about Martin Luther King Jr., Clemente said that King “changed the whole system of American style.

“He put the people, the ghetto people, the people who didn’t have nothing to say in those days, they started saying what they would have liked to say for many years that nobody listened to,”said Clemente. “Now with this man, these people come down to the place where they were supposed to be but people didn’t want them, and sit down as if they were white and call attention to the whole world Now that wasn’t only the Black people, but the minority people. The people who didn’t have anything, and they had nothing to say in those days because they didn’t have any power, they started saying things and they started picketing, and that’s the reason I say [King] changed the whole world.”

After King was assassinated in 1968, Clemente, as the lead union representative in the National League, successfully organized a strike of players that led to Major League Baseball delaying the start of the 1968 seasons

“We are doing this because we (white and Black players) respect what Dr, King has done for mankind,” Clemente and white Pittsburgh Pirates star Dave Wickersham said in a joint statement to the Pittsburgh Press in 1968. “Dr. King was not only concerned with Negroes or whites but also poor people. We owe this gesture to his memory and his ideals.”

As a union leader, Clemente also played a key role in backing the controversial case of African-American outfielder Curt Flood that went all the way to the Supreme Court and forever changed baseball labor relations.

Flood had protested the “reserve clause” system that allowed major league teams to re-sign perpetually with no option of being a free agent. Flood wanted to bring a lawsuit against the system, comparing the system of forcing a player, blocking them from free agency, with “slavery.”

“A well-paid slave is, nonetheless, a slave,” Flood remarked in a 1969 television interview as he struggled to gain support not just from the public, but from other players for his cause.

On December 13, 1969, in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Curt Flood was walking into one of the most important meetings of his life: the executive committee meeting of The Major League Players Association. He was nervous as all hell about what he was about to ask his fellow players to do — back him in a controversial lawsuit.

Months earlier in October, Flood, a 7-time consecutive Gold Glove-winning center fielder, who helped lead the Cardinals to two World Series victories in the 1960s as team co-captain, was traded away after spending 11 years of his life in St. Louis. Not only was Flood being asked to move away from his family and give up his various business interests in St. Louis, but he was being asked to report to the Philadelphia Phillies, one of the most racist teams in baseball at the time.

Today, a little over fifty years later, veteran players can block trades to certain teams, but in 1969, players weren’t allowed to do so. Players were also barred from seeking free agency by the so-called “reserve clause.” Meaning, team owners could decide to trade whoever regardless of seniority.

Flood didn’t want to go to the Philadelphia Phillies, but he needed his union’s support to fight them in court. He needed to hit a home run with his union that day in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

As expertly recounted in Barry Synder’s book A Well Paid Slave, many players in the union meeting that day were skeptical of Flood’s decision to sue. Two previous lawsuit attempts — 1949’s Gardella v. Chandler case and the 1953’s Toolson v. New York Yankees case — had both been lost, and lawyers predicted that Flood stood little chance of winning.

That winter, the player’s union was in the midst of tough contract bargaining with the owners and felt the case would be a distraction. Many players in the fledgling union thought that the union should instead focus on raising players’ wages and improving working conditions, not try to challenge the “reserve clause,” the Mt. Everest of baseball rules.

On the flight down to San Juan, even Flood’s teammate, the Cardinals’ own union player representative shortstop Dal Maxvill, told Flood that he shouldn’t go forward with pitching the player’s union on backing the lawsuit.

“Why are you doing this to yourself,” Maxvill told Flood on the flight. “Do you know that you are going to be out there like Lone Ranger?”

The following day, when Flood met with the Player’s union, Flood told them he was going to sue Major League Baseball for infringing on his rights as a worker to be employed by whom he pleased, with or without their help.

Many of the players in the room were skeptical. Tom Haller, the All-Star catcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers and future general manager of the Chicago White Sox, asked Flood bluntly if his decision to challenge his trade to Philadelphia was based on race.

“I didn’t want it to be just a Black thing,” Haller recounted in A Well Paid Slave. “I wanted it to be a baseball thing.”

There were only two other Black men in the meeting: Reggie Jackson and Roberto Clemente.

Jackson had just finished his second year in Major League Baseball, and the young phenom hadn’t endured the indignities of an 11-year veteran like Flood. Jackson began to question Flood’s decision. At one point, he even mocked Flood, a much better-paid veteran, as the only player who could afford to take on such a legal challenge.

The mood in the room seemed uncertain whether players would get behind Flood.

Then, Roberto Clemente, entering his 14th season, stood up and started to argue vehemently on behalf of Flood. Clemente had some experience organizing around racial issues in baseball. The year prior, he had led an effort to get Major League Baseball to reluctantly agree to delay the start of the season after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated.

Clemente recounted how the lack of free agency had forced him, as a Puerto Rican player, to play in a racist city like Pittsburgh, where he faced frequent taunts from fans and journalists, instead of a more welcoming environment like New York, which had a large Puerto Rican population.

According to Clemente, the imbalance and lack of free agency not only cost him the opportunity to play in a less racist environment but, according to his calculations, had cost him $300,000 over the course of his career.

Clemente repeatedly implored the players to back Flood. When he finished speaking, the barbs at Flood had stopped. As Synder recounts, “…the tone of the meeting soon shifted from whether the players would back Flood to how.”

Fifty years later, Clemente’s son, Roberto Clemente Jr., told me in 2020 that his father had specifically arranged the meeting on his home turf in Puerto Rico.

“As the National League’s player representative, Dad knew how important this meeting was and he wanted to have it there in Puerto Rico,” Clemente Jr. told me in an interview.

Now, five years later, after Clemente Jr. decided to endorse Trump and get into conservative politics, there has been no mention of his dad’s union activism on behalf of racial justice.

Instead, Clemente Jr., who long pushed to do Spanish-language broadcasts for the Pirates, is finally going to get his chance. His role as Clemente’s son is enhanced by a film that completely depoliticizes Clemente.

But for many of us, Clemente is so much more. Clemente was a fighter whose politics continue to inspire us.

“Clemente really represents the values of a union town like Pittsburgh in so many ways,” says Guillermo Perez, President of the Pittsburgh Labor Council for Latin American Advancement. “And from the Latinx perspective, he set a great example by overcoming so many obstacles, and as I said, never compromising on his sense of identity as an Afro-Puerto Rican from a working-class family.”

Donate to Help Us Continue to Honor Roberto Clemente in Our Labor Reporting