I. The Stakes: “Right-to-Work” in Pennsylvania

Washington, Pennsylvania — When I arrived at the high school gymnasium where the Democrats were holding a convention to pick their nominee for the crucial PA 18 Western Pennsylvania Congressional special election, I couldn’t help but think of my PapPap, Regis “Rege” Holden, a long-time leader of the Democratic Party in the land of my birth, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania.

I was nervous as all hell and found myself searching for my grandfather’s old political ally—former State Senator Allen Kukovich of Manor—the borough where my grandfather had been a leader in the bricklayers’ union and a pioneer in the post-war field of vocational education. I had been gone from Western Pennsylvania for a long time and hoped Kukovich could give me the skinny on what was happening here.

I had spent the last 13 years away reporting on the drug war in Brasil, working as labor reporter at Politico in DC, and crisscrossing the country filing stories from more than 30 states over the course of a decade.

After getting fired in the union drive at Politico, I had covered the tough fights to organize the South at Volkswagen in Tennessee and Nissan in Mississippi, and even helped persuade an ironworker from Wisconsin named Randy Bryce, a longtime loyal reader, to challenge Speaker of the House Paul Ryan.

But now I was returning home for another consequential election—the special election for the Congressional seat of Pennsylvania’s 18th district, set to be held on March 13th.

If labor were to win in this district, it would set the playbook for the coalitions needed to win back Congress in 2018. If labor lost, it will almost surely open the door to anti-union, so-called right-to-work laws like those we saw infect neighboring West Virginia the year before.

During the past three years, the unimaginable had occurred. A tidal wave of “right-to-work” laws had spread north from the South to infect the states of Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, Kentucky, and West Virginia and could cost the labor movement hundreds of thousands of dues-paying members.

Instead of being able to go on the offensive in the South, where the labor movement has grown as the auto industry relocates there, labor instead finds itself defending against “right-to-work” laws in the North.

If we do not win in the 18th, right-to-work could very likely come to Pennsylvania and bankrupt the labor movement in one of its last strongholds.

The battle will be fought in the hills and river valleys where my grandfather had organized teachers and bricklayers, where my mother had struck for union recognition at Volkswagen in the 1980s, and where I had watched my father fight plant closings as a UE union rep.

A win in the 18th, which has previously been held by pro-union Representative Tim Murphy, would offer a badly needed boost of energy to a labor movement that had spent the last decade on the defensive.

The candidate this time around though was very different than Murphy, who was a “silent c” conservative and who, as a psychologist, touted bipartisan accomplishments on mental health while pleasing unions in the district by voting against the repeal of federal prevailing wage laws.

Prevailing wage laws establish a floor for construction wages on federal and state contracts, ensuring that government contracts increase construction wages as opposed to driving them down. In the past, Murphy had been one of two dozens Republicans to block Tea Party attempts to repeal them.

But the GOP nominee for the district, Pennsylvania State Rep. Rick Saccone, has done the unthinkable for a Southwestern Pennsylvania Republican—he has sponsored legislation to enact “right-to-work” laws as well as repeal prevailing wage.

A win by Saccone would send a signal to other Western Pennsylvania Republicans typically hesitant to take on labor directly that they could go to war with unions in Pennsylvania and open the door for the Republican-controlled state Legislature to pass “right-to-work” laws.

The stakes in the 18th District could not be higher.

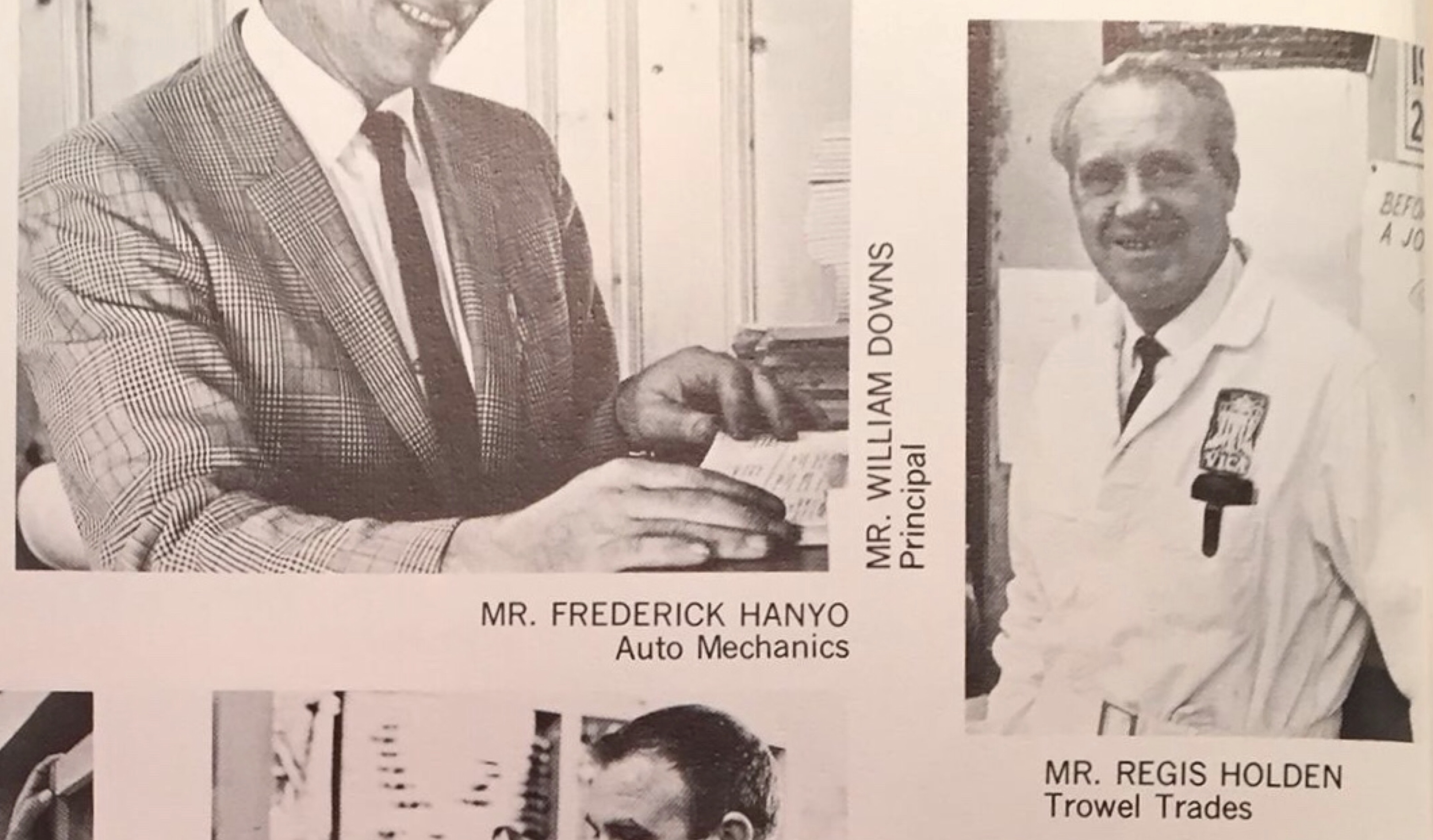

II. The Bricklayer, Who Never Went to High School, But Taught At One

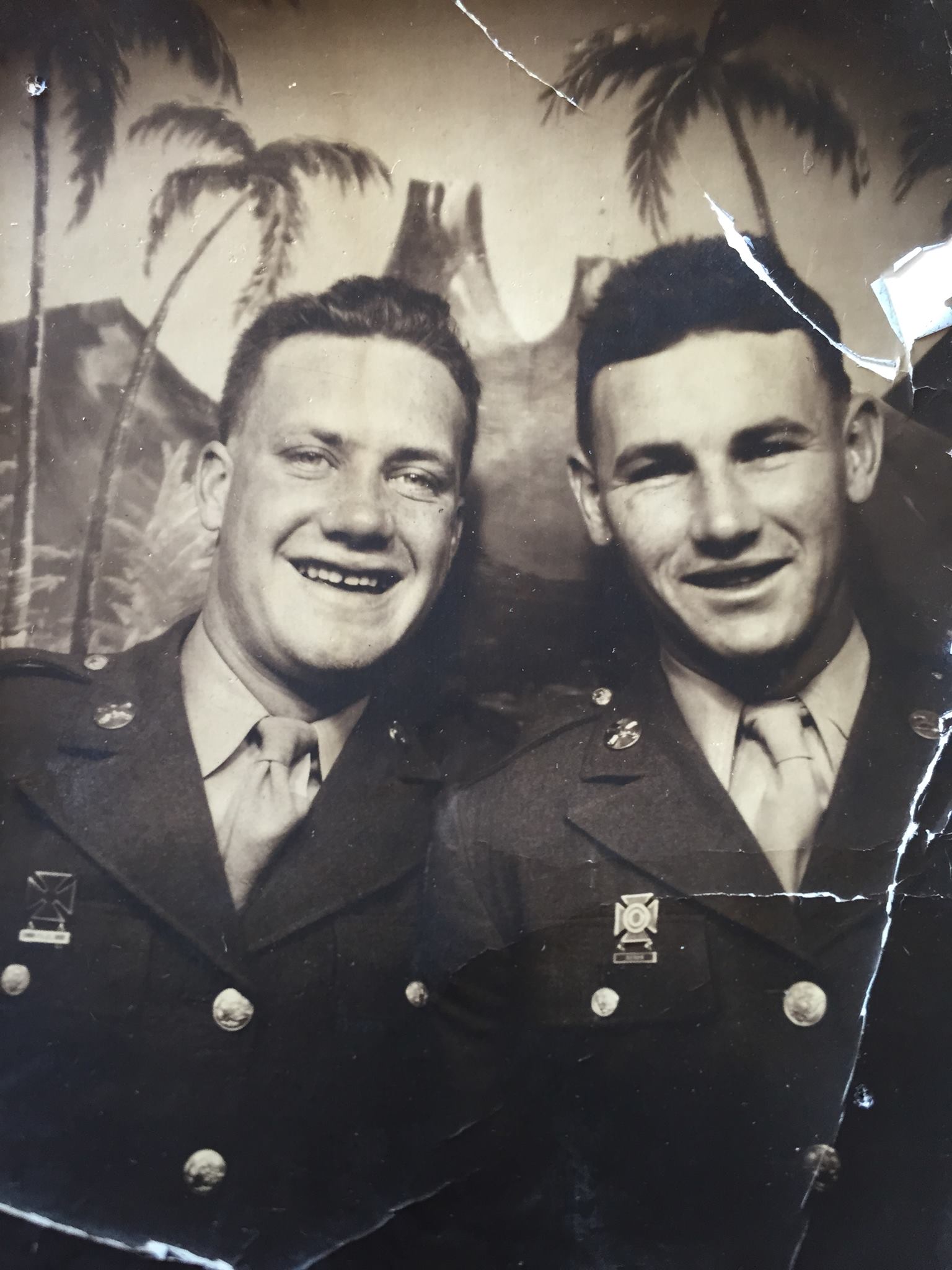

(Regis Holden (left) during World War Two)

On paper, the 18th technically seems winnable—it has 70,000 more registered Democrats than Republicans and contains a whopping 76,000 union members.

However, since the enactment of NAFTA in the mid-1990s, which cost my native Westmoreland County thousands of jobs, it had not once voted for a Democrat.

Two years after my birth, in 1988, the county voted for Michael Dukakis 55-44 percent, in a year in which he won only eight states. In the last election, the county went for Trump 63-32—and this despite the county still maintaining a voter registration margin of 100,000 more Democrats than Republicans.

The demographics of Westmoreland closely mirrored those of the district where 58% of voters backed Trump in the 2016 election. With the district having 76,000 union members, a strong pro-union campaign highlighting Saccone’s assault on labor could carry the day and stop “right-to-work” at the West Virginia border.

Surely, a path lay to victory in this district. And if anyone knew how to win this district, it would be my PapPap’s old political ally Allen Kukovich. So I found myself desperately searching the stands for him.

Finally, in the 11th row of the high school bleachers, I found the white-haired Kukovich sitting with his wife as they waited for the special nominating convention to begin.

I hadn’t seen him in more than 15 years when I was still a member of the College Democrats. Immediately I introduced myself as Rege Holden’s grandson and he was pleasantly surprised to learn that Rege Holden’s grandson had become a labor reporter. Boy, I wish PapPap could have been there.

At a special election convention for state representatives nearly 40 years earlier, my grandfather had introduced Kukovich when he was vying for the nomination at the convention. The local newspapers were predicting that Kukovich would come in third

“There were a lot of Democrats that were against me because I wasn’t one of the good old boys,” said Kukovich. “I was sort of a reformer”.

One person, who was with the 30-year-old, Kukovich that day was my 52-year-old grandfather.

My PapPap, the son of an Irish-English immigrant, had dropped out of junior high during the Great Depression to work in a flour mill. When World War II began, he attempted to follow the lead of his four older brothers who enlisted shortly after Pearl Harbor. He twice tried to lie about his age to enlist and finally did so in 1943.

Assigned to a rear echelon anti-aircraft battalion guarding Omaha Beach, my PapPap instead volunteered to work as “suicide jockey” in the racially integrated Red Ball Express, volunteering to drive gasoline trucks up to the front lines often under threat of strafing and enemy fire. The unit was 75 percent black. While scrappy white guys like my grandfather had the option to volunteer or stay with their units, the black drivers had been forced into this hazardous front-line mission.

Landing a few weeks after D-Day, he participated in the breakout from Normandy, the Battle of the Bulge, later returning to his anti-aircraft unit to defend the port of Antwerp from V-2 Rocket attacks; dozens of men in his unit were killed when a V-2 rocket hit his camp one night.

After the war, he again went back to work as a gasoline truck driver. Then, he got his big break—he was accepted for an apprenticeship in the bricklayers union.

He worked for more than a decade as a bricklayer, sometimes alongside my great-grandfather, Julio DiBagnio and his crew of Italian trade unionists, who had fled Mussolini. He later married my Nonni, and thank god he did.

Because in the late 1950s, he got his second big break. He was working as a foreman building Hempfield High school when the superintendent of the school district asked if he wanted to work as a high school teacher in the new field of vo-tech education.

My PapPap was baffled. He hadn’t even gone to high school, so how was he going to teach it?

The superintendent cut him a break and said that he could teach for a few years while going to school at night to get his credentials. He had dropped out of school, but my Nonni loved to read and would read many of his textbooks while he was out working side jobs after school to earn extra money.

Not willing to leave his union organizing at the construction site, my grandfather continued to organize in his high school and would scold his buddies who portrayed teachers’ unions as greedy parasites.

My PapPap would go on to be a pioneer in the field of vocational education and was one of the founders of Westmoreland County Community College.

That day at the nominating convention in 1977, when the party machine was against Kukovich, my grandfather gave the speech introducing Kukovic.

“He had credibility among a lot of people with whom I had no connection,” said Kukovich of my grandfather’s support. “He had a larger sphere of influence because of who he was and what he had done.”

“He was on the school board, he wasn’t just parochial about his district. He was concerned about education in the whole area and respected among his peers,” said Kukovich. “He would learn, he would go to association meetings, he would really participate. He had credibility. He was fair with people.”

The efforts by my grandfather and others paid off that day as Kukovich won the Democratic nomination for State Senator.

For the rest of his life, my grandfather would take great pride in his role in introducing Kukovich. As a state representative, Kukovich would take the lead in passing the Children’s Health Insurance Program in the early 1990s, which would serve as the model for how Democrats passed it at the national level.

In 1996, Kukovich would defeat a conservative Democrat in a bid to move up to State Senate. Kukovich would be the last Democratic State Senator elected in the area.

“Back then, we didn’t worry about Republicans,” said Kukovich. “Democrats running against other Democrats was always where the real action was.”

III. The Political Devolution of Westmoreland County

From 1932 to 2000, Westmoreland County had gone solidly for the Democratic Party in every election with the exception of 1972, when Nixon had won 48 states against McGovern.

But then in 2000, the district swung for Bush, and in every election since then, it went for Republicans by increasing margins.

In 2004, outside political interest groups would spend a combined $1.2 million to defeat Kukovich in his state senate re-election. Prior to this, no political candidate in Westmoreland County had ever spent more than $200,000.

“I’ve seen it change from the standpoint of an old father,” said Kukovich, who is now 70, battling pancreatic cancer, and recovering from a stroke that left him in the hospital for 40 days this summer.

During the housing boom of the 1990s, as mills closed down, wealthier people fled the increasingly underfunded racially integrated school districts of the eastern half of Pittsburgh’s Allegheny County.

“I always used to see those developers’ signs for the new homes that they were building and there would be a little note on the bottom promoting the school district and the school districts were all primarily white,” said Kukovich. “They were voting very conservative. Even if their parents were voting Democratic.”

The woods and hills in which I learned to track deer with my PapPap were now eyesores filled with McMansion subdivisions.

The only thing more unrecognizable than the landscape of Manor these days are the people. They are newly rich and nothing like the union leaders, PTA members, and American Legion buddies, who had populated the BBQ’s held behind my PapPap’s house.

At the same time that the school district became more suburbanized, NAFTA damaged the county’s remaining industrial base. With mills and factories closing, the region lost one of the few social organizations still holding the district together.

“I would meet a lot of these forty-somethings with kids in schools and the vast majority were from Allegheny County and they moved out to buy a bigger lot,” said Kukovich. “They really weren’t connected to the local community except through the school district.”

IV. The Union Busting Newspaper that Payday Intends To Fight

Billionaire Richard Mellon Scaife’s massive investment in the Tribune-Review over a 30 year period dramatically changed the politics of Westmoreland County. (The American Spectator)

The lighter fluid to the kindling of the growing conservative fire in the district came from billionaire Richard Mellon Scaife.

In 1970, the banking and oil heir bought the Greensburg Tribune-Review. The paper slowly started to gain traction in Westmoreland County, but still faced competition from a variety of regional newspapers.

Then in 1992, the Pittsburgh Newspaper Guild went on strike at the Pittsburgh Press, forcing workers at the Post-Gazette, which shared their printers, to go on strike with them for several months.

Taking advantage of the news desert created by the disappearance of the two papers, Scaife used the strike to expand his market share into Pittsburgh. At a time when other papers were contracting in Westmoreland County and union newsletters were going out of business altogether, the right-wing Tribune-Review was growing.

“There was a way that the hard news was altered by Scaife and that had corrosive effects for a number of years,” said Kukovich. “If that’s their major newspaper and they are watching Fox News, and you have a new influx of people moving out to the subdivisions, and the old manufacturing towns of Monessen, New Kensington, Jeanette are losing population and aging, that’s what did it”.

“35 years of the Greensburg Tribune-Review and Scaife’s bias had a role to play in that [change],” he added.

And that’s exactly why I came home. The local papers that most people read in Westmoreland say nothing about organizing or give folks any sense of how they could push back. Even the liberal Pittsburgh Post Gazette, while doing an excellent job diagnosing the problem, did little to offer a prescription for a way out of this.

It would fall to Payday Report to stir up morale, call in reinforcements, and to present valuable questions for organizers on how to continue the struggle.

As a veteran labor reporter, my goal has never been to persuade people to the union cause, but to provide valuable information to those organizing so that they would keep organizing and convince other people to join them.

Often, we see big far-reaching theoretical and political think pieces, but rarely do we see reported stories that ask fundamental questions of organizing: how do you get people to show up to a meeting? How do you give someone the confidence to become an organizer? Finally, how do you keep pushing as organizers when the odds seem overwhelming?

I would go in and out of small towns like Horicon, Wisconsin, Taunton, Massachusetts, Paducah, Kentucky and Canton, Mississippi. I would tell what seemed like isolated labor stories and figure out ways to connect them to larger fights.

Throughout my career as a labor reporter, I’ve kept my grandfather’s thermos on my desk to remind me of the kind of man I wanted to be and the courage I had hoped to display as a labor leader someday.

At my PapPap’s funeral in 2001, dozens of men came up and shook my hand. They told me my grandfather had saved them from poverty and taught them the lessons of solidarity.

The firm handshakes of those labor leaders have stayed with me since that day back when I was 15 years old.

I always remembered what he said about firm handshakes anytime I was going into tough labor struggles to talk to workers, whose unions were losing tough, ugly labor fights, and I had to figure out a way to win their trust.

I faced no greater challenge than in the winter of 2013 during the union drive at Volkswagen in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

V. The Myth of Westmoreland County in the Anti-Union Campaign At VW in Chattanooga

Anti-union workers at Volkswagen in Chattanooga frequently cited the 1988 closing of an unionized Westmoreland County Volkswagen plant against unionization efforts. (No2UAW)

In the winter of 2013, I had gone South to Chattanooga, Tennessee, motivated by the fact that union-busters had talked so negatively about my home region of Westmoreland County.

While organizing the plant, anti-union forces distributed flyers that said “UAW=Death” highlighting a Reuters article about 19 workers, who had killed themselves following the closing of the 5,000-person Volkswagen plant in nearby New Stanton, Westmoreland County in 1988. It was some dirty fucking bullshit.

I remember all the suicides that happened following plant closings and how painful they were in my community, and it pissed me off to see these fucking scabs abusing their legacy in this way

Anti-union forces told the Southern workers that greedy Northern workers who had supported the UAW and gone on strike were the cause of those suicides. I was furious. My mother had participated in those strikes. I figured, as a labor reporter, I ought to go down there and represent my people, who were being smeared.

I started working my contacts in the “union avoidance” community to see if anyone could provide me with advance knowledge of what the anti-union forces intended to do so that I could warn the workers.

I made inquiries among people in the union-busting community to see if anyone knew what the playbook was. I wanted to get into the ballgame in Chattanooga to defend the honor of the people I grew up with in Westmoreland, County.

Eventually, I got a union buster to leak to me the full anti-union game plan that top GOP political operative Grover Norquist intended to use there. It showed something that I hadn’t seen before: a massive TV ad buy aimed at persuading the entire community to turn against Volkswagen workers who wanted to vote union.

Instead of making it just a question among workers at the plant, Norquist hoped to use the threat of the plant closing to get community members to put peer pressure on Volkswagen workers.

I had to go South and warn the workers.

On my first day in Tennessee, columnist Dave Cook wrote a column on the front page of the Chattanooga Times Free-Press welcoming me to town and encouraging folks to come to a community presentation I was giving on what the union busters planned to do to divide the community members.

Almost immediately, the threatening emails and messages began pouring in, warning me to go back North.

When I went on the radio and started talking about the decisive role played by Union army troops down South, I was quickly corrected by Southern organizers who took great pride in how the hill folks of Southern Appalachia had also taken up arms against the Confederacy.

Orchard Knob Battlefield, Chattanooga, Tennessee (Mike Elk)

During my first visits to Chattanooga in the winter of 2013-2014, I stayed across the street from Orchard Knob Battlefield in the home of Michael and Keely Gilliland, a couple who had met at an evangelical church lock-in during high school and became devout anti-racist organizers during their marriage together.

Michael, a native of Hixson, Tennessee, taught me how the Appalachian counties of eastern Tennessee had risen up against the Confederacy, tens of thousands of men and women, assisting the advancing Union army by hiding freed slaves and engaging in guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines.

For over a month the troops were besieged and reduced to eating horses. Whole counties in the Appalachian mountains of Northern Alabama and Eastern Tennessee formed their own breakaway country of Nickajack and refused to participate in a war for slavery. More than 40,000 Tennesseans would take up arms against the Confederacy.

As I toured the battlefields of Chattanooga, Gilliland explained to me how those strands of Southern resistance to the wealthy elite had continued to this day and wondered why people in the North were ignoring stories of resistance that could inspire so many.

The stories Gilliland told me of the pride he felt in his ancestors who had fought were much like the stories my PapPap told me of the pride in his family’s trade unionists.

“What does it mean to be Southern? Is the Confederacy really ‘more Southern’ than the civil rights movement? Is an ingrained distrust for unions more Southern than ‘Moral Monday?’ Who gets to say?” Gilliland asked me one day.

I stayed down in Chattanooga on and off throughout the winter and watched as this new trend of dark money flowing into union elections slowly eroded support. Unfortunately, my attempt to warn the community about the coming onslaught of union buster ad buys did not pay off.

On Valentine’s Day 2014, the union vote was held and came up 86 votes short. I stood outside the plant gates in the rain as the leaders of the anti-union groups celebrated

“At least we avoided the fate of Westmoreland,” ‘Vote No 2 UAW’ leader Mike Burton told me as a group of anti-union workers celebrated their defeat of the UAW.

I was angry as hell and starting to lose my temper. I confronted Burton, saying how dare these people talk that way about the people I grew up with in Westmoreland County.

Then a 5’7” pro-union Volkswagen worker named Wayne Cliett slowly pulled me aside to prevent me from doing something stupid. Despite having spent the past three years fighting every day on the plant floor for a union, he calmly went up to the anti-union folks and shook each one of their hands and congratulated them on defeating the anti-union drive.

When I asked Wayne why he congratulated the crew, he told me that he would need to win these people over to the union cause.

“I’m a stubborn man,” said Cliett. “Some are talking about quitting. I will be walking into the plant on Monday with my head held high and preaching the message of solidarity.”

This was the dedication of a Southern organizer; someone who knows that the struggle is long, but was prepared to accept any price. I had gone South, thinking I would teach the Southerners a thing or two about unions, but instead, they taught me what true courage was.

VI. The Disparity In Which Workers Get Media Coverage

Mike Elk was the only national reporter to cover the Historic “March on Mississippi” against Nissan attended by over 5,000 Southern union supporters (Mike Elk)

A few months later, the beltway publication Politico cold-called me, telling me they had been impressed by my reporting in Chattanooga. They offered me a position making $70,000 a year and, badly in need of a job, I took it. However, I soon found myself at odds with management over journalism ethics, printing dubious lies from union busters, and chafing against their decision that they didn’t want to do “man on the street” style labor reporting.

They started accusing me of being biased in favor of unions, demanded that I work 60 hours a week, and made the work environment very hostile.

I thought of my PapPap, my mother, and my father, and all the workers I had covered. I asked workers to risk their careers to speak out. Who would I be as a labor reporter if I didn’t show that same kind of courage?

So I decided to make a Curt Flood-style statement against working conditions in the industry. I called up the Washington Post at the time and told them my desire to unionize.

At the time, the Washington Post published an article entitled “Why Don’t Internet Journalists Organize”, which laid out the case that my sentiments were the exception to the norm and that digital media unionization was extremely unlikely.

However, the attention that the debate created, coupled with my ability to get into the press for calling out Politico while still employed there, proved a point that when journalists organized, it received a ton of publicity. Four months after my protest at Politico, Gawker announced they had unionized and, seizing on the momentum of the Gawker drive, five other digital media outlets including the Guardian, Vice and HuffPost followed. (I don’t take credit for any of those drives, but I did demonstrate that when you are in the news industry and speak out about workplace abuse, it gets coverage).

In the following three years since the Washington Post published their now infamous article arguing that organizing among journalists was unlikely, more than two dozen digital media outlets have gone union, including, most recently, the 350 workers at Vox Media and the reporters at the Los Angeles Times, which until 2016 had successfully resisted unionization of its staffers for the previous 125 years.

Following the union drive at Vice, Politico, sensing that there was real momentum in digital media unionization, decided to fire me while I was on vacation attending my father’s election as Director of Organization for the United Electrical Workers (UE) in Baltimore in the summer of 2015

As a result of the illegal firing, I won a year’s salary as a settlement and decided to go South and start Payday Report.

I wanted to start my own publication in order to cover the massive effort to Organize The South that had resulted in 150,000 Southerners joining unions in 2015, making the South the fastest growing region for unionization in the U.S., all while the media was ignoring the story.

I had seen what happened in digital media unionization when workers got a ton of positive coverage and how it helped workers organize. I had also seen what happened at Volkswagen when workers got bombarded in the media with lies about how unions would hurt them.

I went back to Chattanooga in the winter of 2015 to report on the struggle to unionize the South. I decided to use my year of salary not to put a down payment on a house, as some suggested, but to found Payday. I wanted to give Southern workers the type of coverage they deserved and expose how oblivious the media had been to the massive mobilization of Southern workers.

In our first year and a half of operation, we have raised over $40,000 from over 600 donors, published over 130 stories, and in one six-month period, put 20,000 miles on a 2003 Dodge Neon that we bought from retired Linesville District Justice Wayne Hanson, a loyal reader, for a mere $700.

I was with black nurses fighting for collective bargaining rights at the Medical University of South Carolina, refrigerator workers in Memphis winning their union on a second try, suburban Episcopal women protesting Trump in Alabama, tire workers in Georgia, and undocumented construction workers dying on the job in Nashville.

I covered the defeat of Boeing workers seeking to unionize in Charleston, only to lose after the company spent $485.000 on anti-union TV ads without any comparable labor press to push back.

A few months later, I marched with 5,000 union supporters and Bernie Sanders in the historic ‘March on Mississippi’ against Nissan. We rent a small house with our readers’ donations near Canton, Mississippi and I wound up filing more than 15 dispatches for both The Guardian and Payday Report. However, that union drive was defeated following an intensive campaign of threats, captive audience meetings, and yet another expensive anti-union TV ad push.

In each of these fights, union organizers complained about a lack of resources. At a time when unions were expanding in the South as the auto industry grew, Tea Party conservatives in the North were passing “right-to-work” laws depriving unions of members along with the vital resources they needed to continue protecting labor’s interests.

Now, we are headed back North to cover the special election for Pennsylvania’s 18th Congressional District and halt the spread of right-to-work in the North.

VII. The Special Convention

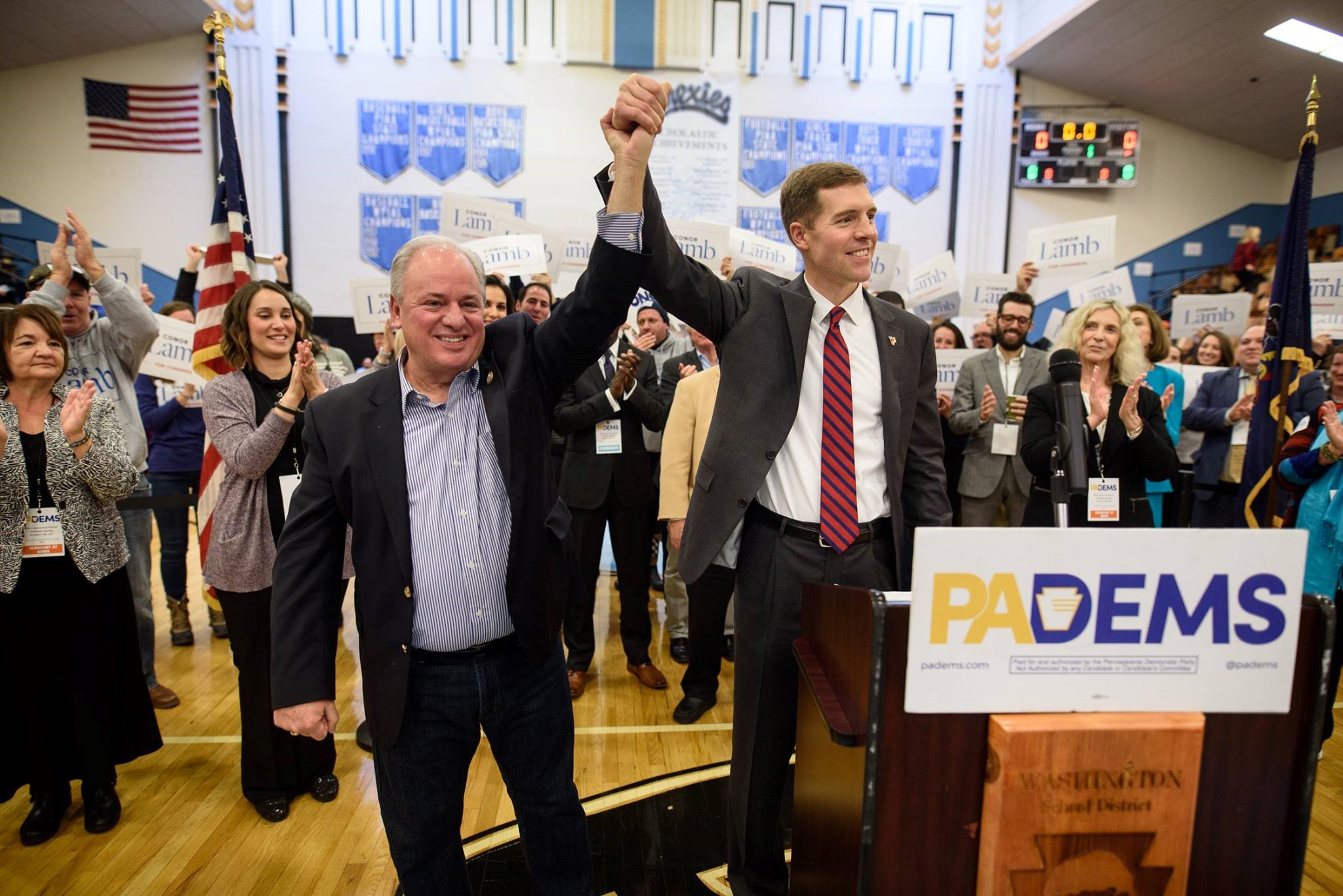

Supporters of Conor Lamb campaign at a special convention to become the nominee for the March 13th Special Election (SaluteMag.com)

As I stood on the sidelines of the gym, waiting for the special convention to begin, I found myself struggling to explain to my PapPap’s old political associate Allen Kukovich where I had been. I kept stopping to think about my grandfather. Here I was, standing as a labor reporter next to one of the last living links to PapPap’s political legacy, trying to get the skinny on what was going down in the district.

As we stood there talking, well-wishers came by and told the 70-year-old Kukovich that they had been praying for him.

Kukovich had been struggling with pancreatic cancer that appeared terminal and earlier this summer had spent nearly six weeks in the hospital recovering from a stroke. The special convention was one of the few political events that he had attended in recent times and longtime Democratic activists were excited to see him.

As a stream of activists passed by, giving Kukovich hugs and telling him that he was in their prayers, the state party chairman eventually approached and asked Kukovich to give the opening prayer.

“In this season of thanksgiving, let us do just that, let us give thanks for our democracy let us give thanks for all that we have and all the good things around us,” the elder statesman told the room. Many attendees who knew him had teared up.

“Let us give thanks for what we can do positively and let us pray to whoever you want or not to pray as you feel best served to do, but provide all your prayers and individual energy to the candidates and the chore that is before us. Let us continue our fight to make this a better world for all people,” Kukovich told the crowd to much applause.

The tone of the day was set early on: to win, Democrats would need to focus on labor to win the seat.

Speaking directly to this point, Congressman Mike Doyle of the 14th Congressional district emphasized that prevailing wage laws would be a central issue in the campaign.

“[Saccone] doesn’t believe that working families should get fair pay for their work,” Doyle told the crowd. “This guy is not for labor, not for working families, not for the middle class, and this guy proudly says ‘I was Trump before Trump was Trump.’”

Despite their political differences, the theme of attacks on unions echoed throughout the speeches of the crowd of seven Democrats, a field ranging from Bernie supporters like Dr. Bob Solomon to pro-life, pro-business centrists like Westmoreland County Commissioner Gina Cerilli.

Cerilli recounted her experience winning back a seat on the Board of Commissioners in Westmoreland County, where Democrats outnumbered Republicans by nearly 100,000 voters but where Republicans had dominated the county commission for the previous decade

“Those Republicans were born and raised in Democrat households, and unions put food on their table. Their parents’ union jobs paid for their education, but once they went to college and made a little bit of money, they moved into a new housing plan and suddenly, it was more convenient for them to be Republican” said Cerilli.

Cerilli emphasized that she would be able to win by focusing on the legacy of organized labor by emphasizing how unions could help young people build a sustainable legacy similar to the one that our grandparents had built in Westmoreland County.

“That Democratic fire will always remain in their bodies,” Cerilli said to the crowd regarding the importance of union issues for winning the district.

I knew in my gut that what Cerilli was saying was accurate. I hadn’t met anyone who was anti-union until I had gone away to Bucknell on a scholarship.

None of my cousins back home, even the “new rich” ones who had started voting Republican, were anti-union. In fact, Trump has appealed to such voters in part by playing up his ties to unions and campaigning against NAFTA.

Sure, you can be a Republican in Western Pennsylvania, but being anti-union in the region is like being anti-Steelers. Support for unions is encoded in our DNA.

Republican Congressman Tim Murphy, while pro-big business and favoring tax cuts, always managed to secure the endorsements of some unions in the district by touting his support for prevailing wage laws and the use of union labor on construction projects.

While Cerilli talked about reaching younger votes by appealing to the legacy of unions that had built Westmoreland County, her crowd of supporters decked in red was notably devoid of young blood. In fact, throughout the audience, all the galleries for candidates seemed to lack young voters except the thirty-somethings sitting en masse under cut-out signs of lambs with the word “Conor” on them.

Lamb was a young leader who exuded youthful vigor. His positive reputation had led to a massive outpouring of support from young Democrats, who respected Lamb because of his honesty and willingness to fight for underdogs.

Earlier in the day, I found myself jumping out of a golf cart provided to transport moderate Democratic candidate Pam Iovino’s elderly voter base to the building when I spotted a buddy from high school who had the same idea to return to the district and make a difference. During my time at the convention, I met a lot of young people who were supporting Conor Lamb.

Throughout his career, Lamb had shown leadership: first as Marine Corps prosecutor taking on cover-ups of rape on Okinawa and at the Naval Academy and then as a prosecutor, where he started a program to mentor the children of drug offenders serving time in prison.

Lamb took the podium and reminded the audience of his proud family legacy.

His grandfather Thomas Lamb had been the State Senate Majority Leader during the 1970s and helped pass key civil rights and environmental legislation. His uncle Michael Lamb had garnered a reputation as a reform-oriented watchdog as Pittsburgh City Controller, taking on Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto for engaging in pay-to-play with developers and shafting workers.

“In my family, we are serious about our religion and we are serious about our education,” said the Central Catholic and University of Pennsylvania graduate. “We are serious about public service and we are just as serious about the Steelers and the St. Patrick’s Day parade”.

“The people and issues we represent require new energy and youthful leadership,” he added.

“I am going to take the fight against their entire anti-middle class, anti-American legislation straight to them,” Lamb concluded, eliciting a round of cheers.

After two rounds of balloting, the assembled committeemen chose the 33-year-old Lamb as their nominee.

Citing his background in the physically demanding Marine Corps, Lamb pledged to run an energetic campaign and knock on as many doors as possible.

Conor Lamb and Congressman Mike Doyle (D-Pittsburgh) (Conor Lamb for Congress)

“There is a long road ahead and I hope it rains and snows every day between now and March 13th, because I meant it when I said that there will be no doubt, at the end of these next few months, in terms of who represents the families of this district,” said Lamb.

For the Democratic party in Western Pennsylvania, Lamb represented a breath of fresh air.

“He presents an image of someone who looks not just like a Congressman, but somebody with some energy and some youth,” said the 70-year-old Kukovich. “I think imagery really matters and I think someone who looks young, energetic, and dynamic is a big help.”

After the race, I bumped into Congressman Mike Doyle, truly a “yinzer’s yinzer” who lived three blocks from the house where I grew up. Doyle told me that in order to win the race, Lamb must zero in on labor issues.

“Tim Murphy split labor in this district because he would give unions the vote on prevailing wage. Rick Saccone is not that kind of Republican,” said Doyle.

“When the bread and butter issue of food on my table is disarmed in a race because the Democrat and the Republican both say, ‘I’m with you on the Davis-Bacon Act, I’m with you on prevailing wage,’ then it goes into other things: guns, immigration and all these other side issues, but prevailing wage is the key bread and butter issue for people in the trades who want to feed their families. That sort of supersedes the side issues,” Doyle said.

“You’re going to see a very united labor vote because I think they’re going to be able to go out to their members and say this is really about feeding your family now,” he added.

A campaign won in Western Pennsylvania on labor issues would not only protect the state against “right-to-work” laws but remind Democrats of the need to embrace labor as they hope to win back control of Congress in next year’s election.

This fight will be crucial for determining whether or not unions can go on the offensive in the South or remain stuck in defensive battles up North.

“I think it could end up being the type of campaign that could be replicated in a lot of other areas,” said Kukovich.

It’s a story that we as a publication intend to tell in ways that the mainstream corporate media cannot. Western Pennsylvanians, like Southerners, have long been misunderstood.

Prologue: The Son of Westmoreland County Who Died Breaking The Siege of Chattanooga

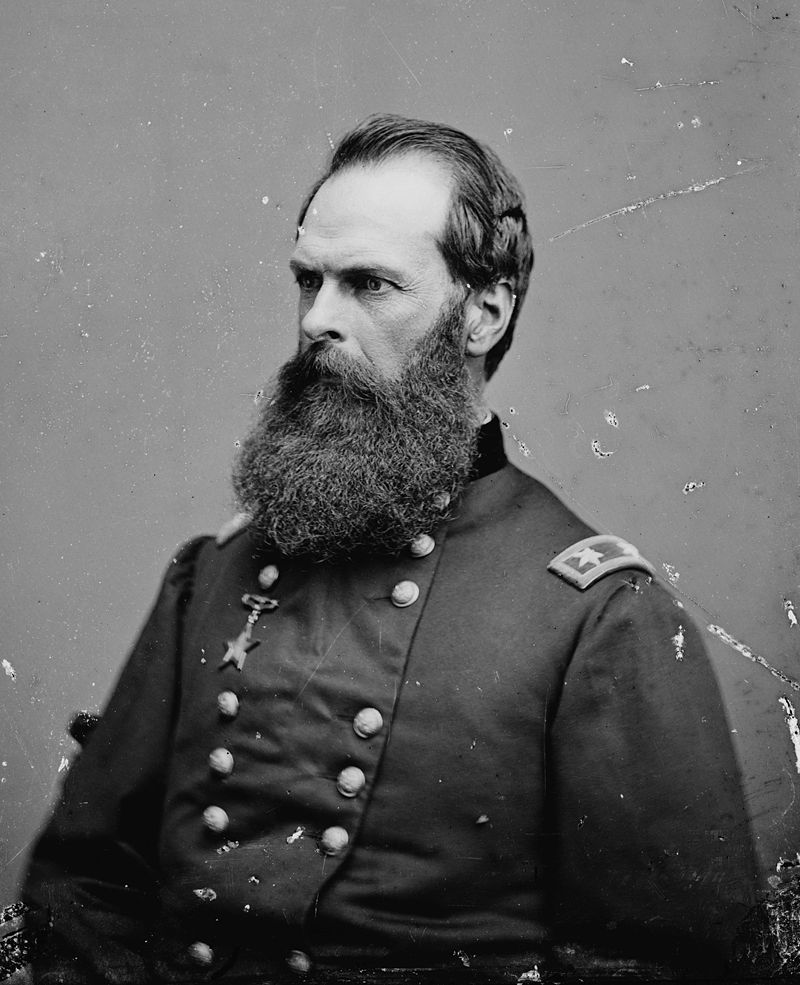

The 16th Governor of Pennsylvania John Geary (Matthew Brady)

As I return home from my time down South, I often find myself thinking of another Westmoreland County native who came back to Western Pennsylvania from Chattanooga nearly 162 years ago: Union army General John W. Geary.

Geary’s leadership had played a key role in breaking the Siege of Chattanooga.

In the fall of 1863, the Union army had advanced rapidly through Eastern Tennessee aided by poor folks in the hills of Eastern Tennesse, who rose up in rebellion against the Confederacy.

Then, in September of 1863, the Union army overextended itself and got divided in the fields of Northern Georgia on the other side of the Tennessee line at Chickamauga. Fearing the total destruction of the army, over 40,000 men desperately retreated back into Chattanooga.

There the 40,000 men of the Army of the Cumberland were besieged in Chattanooga by the Confederate armies holding the high ground around the valley and cutting off access to the Tennessee River.

The Union men began to starve, forced to eat horses and dig up plants. The possibility of surrender was real and would have dramatically changed the course of the Civil War.

Then, on the night of October 26th, 300 Union men floated down the river on pontoon boats toward Confederate artillery positions and troops. In the early morning hours, the men landed at Brown’s Ferry and quickly drove away the company of Confederates guarding it.

The opening of the ferry allowed the Union army to rapidly deliver reinforcements and food to the besieged soldiers.

On the night of October 28th, the Confederates attempted to counterattack and drive the forces off.

Guarding the key link in the Union defense that night were 1,500 men, many from Western Pennsylvania under the leadership of John W. Geary protecting Wauhatchie Station.

Shortly after midnight, the Confederates attacked and nearly surrounded the Union soldiers. In the midst of the battle, Geary’s son Edward was shot. He died in the arms of his father.

Enraged by the death of his son, Geary began screaming and motivating his men to repel the surprise attack.

A lot of Geary’s Westmoreland boys would die far from home, falling alongside the Eastern Tennessee scouts who served with them.

Despite being badly outnumbered and suffering over 300 casualties, Geary was able to hold off the Confederates until his men were reinforced.

Geary’s courage that night in Chattanooga made him a hero after the Civil War and, when he returned home, he won election as the first post-war Governor of Pennsylvania in 1866.

As Governor, he became a champion of working people, supporting the Pennsylvania labor movements that my family and many others benefited from.

Geary began the fight for free compulsory public education, which would take nearly 30 years to achieve. He passed the state’s first mine safety laws following the Avondale mine explosion in 1869 that killed 111 people. He championed the cause of early unions in the state, took on the railroad industry, and vetoed over 390 bills passed by his own Republican-controlled legislature that he felt were in the interests of big business.

In 1872, he attempted to challenge incumbent President Ulysses S. Grant’s corrupt Republican administration by running on the Labor Reform ticket. His band of brothers from that dreadful night in Chattanooga also served as his band of brothers in these other heroic efforts.

In other words, the foundation of the labor movement in Western Pennsylvania was laid by the men who died that night in Chattanooga, men like John Geary’s son, Edward.

Now the script has flipped. The battle has come home; the anti-union scabs have arrived in the hills of Western Pennsylvania, and my region is under siege. The stakes are enormous. If we can stop them here, we can halt the spread of right-to-work and devote our full resources to organizing the South.

I’ve brought my little barnstorming ballclub, Payday Report, home from Eastern Tennessee to tell this epic story. We’re drawing a line in the hills of Southwestern Pennsylvania, and like John Geary, we intend to fight!

A native son of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, Mike Elk was born and raised in part in Jeanette, Pennsylvania. He currently covers Appalachia and the South for Payday Report and the Guardian. He currently resides on the cliffs overlooking the Monongahela River and the Battle of Homestead Historic Site.